Women, Migration and the Building of Australia

Women, Migration and the Building of Australia

Settlers and Defining “Australian”

The University of Melbourne Archives contains papers of nineteenth century European settlers and squatters, especially in Victoria. Within these collections are letters which provide insight into everyday life for women in the colony of Victoria.

For example, Mary Anne Sibella Stephen (1825-1890) married Scotland-born pastoralist John Carre Riddell on 22 October 1846. John later became a politician, appointed first as non-official member of the Victorian Legislative Council in 1852 and then representative for West Bourke (1860-77).[i] The Carre Riddell collection contains Mary Ann Sibella Riddell’s Lay of the Far South (Melbourne: J.Davy and Sons, 1868), a twenty-four page rhyming ode, encapsulating a contemporary colonial settler mindset:

‘Bright are the shores of the Southern sea!

Tho’ there no trace of man’s hand may be.’

Of particular interest for the social history of early Melbourne are “Scribbling Journals” or “Rough Diaries” held in Unit 2 which are a valuable source for the everyday life of young upper-class women residing in Elsternwick. Unit 3 includes the “Scribbling Journals” of Mary Riddell and her daughters Annie and Bessie (1872-1875, 1877-1879, 1884-1885) which outline the women’s schedules, social visits and contain receipts for fashion and household and grocery items. Notably, Mary’s diary entry on 17 February 1875 suggests that the Riddell’s domestic staff were predominantly Irish and describe the novelty of the family cooking for themselves when their cook was granted leave on St. Patrick’s Day.

Mary Anne Sibella Riddell’s diary for 12 April 1843 - 3 August 1846

For a female perspective on outward migration, see the diaries of Mrs. Elizabeth Joyce née Robinson held in the Joyce Family collection 1975.0101. Elizabeth’s husband, Thomas Joyce was an ironmonger, who secured a lucrative contract to supply oil lanterns to London’s Metropolitan Police, subsequently expanding his business interests to oil and shipping.[ii] Their youngest son, Alfred, emigrated to Melbourne on 7 September 1843 and, following some initial financial difficulties, became a prominent landowner and stock producer on the upper-Loddon river.[III]

![Albert J. Wong [photographer], “Louisa Bishop”, no date, Bishop, Joseph and Family, 1965.0017.00018.](https://library.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/image/0007/2616559/1965-0017-00018-00001.jpg)

“Louisa Bishop”

no date

Bishop

Joseph and Family

1965.0017.00018.

Elizabeth Joyce’s diaries, as well as letters to Alfred from 1846 and 1852, can be regarded as companion pieces to his own memoirs, published as A homestead history / being the reminiscences and letters of Alfred Joyce of Plaistow and Norwood, Port Phillip, 1843-1864 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1942) and provide insight into a family separated by vast distances.

The Bishop Family migrated to Victoria during the goldrush, settling in Beechworth, before transferring their coach building business to Euroa. Moving to Melbourne in the 1880s, one son became proprieter of “The Australiasian Coachbuilder and Saddler” journal, which was illustrated with these, now digitised, family photographs.

While less numerous, the University of Melbourne Archives also holds some diaries of non-elite women. One such collection is that of Elizabeth Jane Leggo (1987.0163). Born in Cornwall in 1837, Elizabeth emigrated to Victoria in 1855 and settled in Eaglehawk (near Bendigo). There she raised a large family and became prominent in the local Methodist Church.

The collection is comprised of Elizabeth’s diary from her husband’s death in 1886 until 1913 which details her life with her children in Ballarat and Bendigo. Elizabeth died on 22 July 1915, at her home in “Benola”, on Forest Street, Bendigo. She was remembered as a seventy-seven-year-old ‘colonist of sixty years’, ‘relict of the late William Leggo, of Eaglehawk, and [a] beloved mother.’[iv]

The Commercial Travellers’ Association

While established in 1880 to provide accommodation and support to male commercial travellers, the CTA’s publication, The Traveller, later The Australian Traveller, (1890 - 1976) and yearbook titled Australia To-day depict many locations around Australia and many photographs contain women.[v]

These romanticised depictions give insight into a middle-class culture of aspiration, facilitated by automobiles and railways, as well as the history of Australian travel advertising (1930s-1950s).

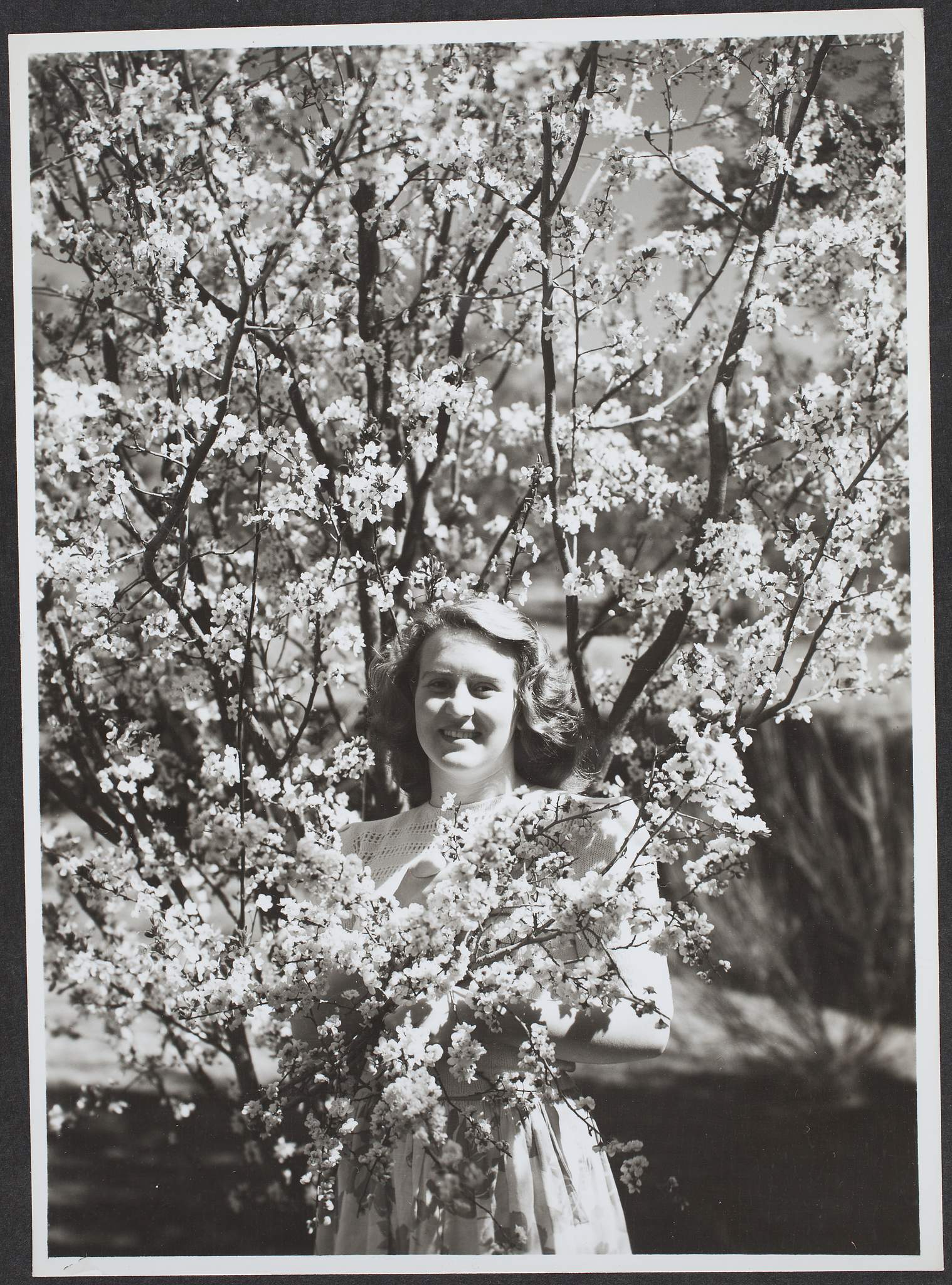

The photographs below have been selected to portray the variety of gendered values which The Australian Traveller seems to have promoted, such as “adventure”, “the exotic” and “family”. These valuable cultural history resources are a small selection of a much larger collection of digitised photographs from the Commercial Travellers’ Association Administrative Records and Publications collection (1979.0162) available online by searching the digitised records section.

-

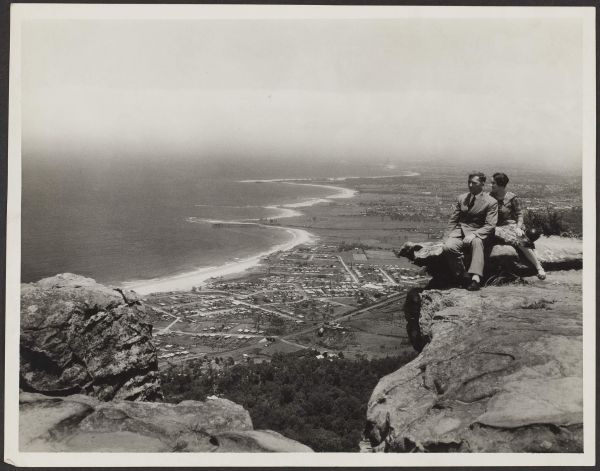

1979-0162-02305-00001.jpg

‘The finest coastal panorama in Australia. The trip is made from Sydney via Bulli Pass along Lady Carrington with big trees, palms, tree ferns, Christmas bush and other attractive flora’. “Sublime Point, Bulli, NSW”, 17 August 1932, Commercial Travellers’ Association Administrative Records and Publications, 1979.0162.02305. -

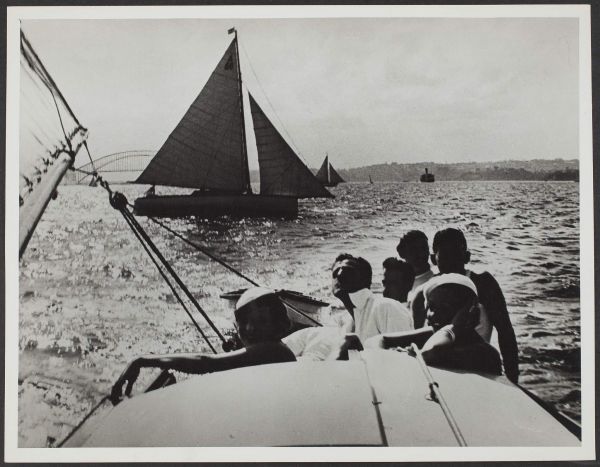

1979-0162-02432-00001.jpg

“Yachting Sydney Harbour”, 6 September 1934, Commercial Travellers’ Association Administrative Records and Publications, 1979.0162.02432. -

1979-0162-02438-00001.jpg

“Surfing girls, Sydney, NSW”, October 1934, Commercial Travellers’ Association Administrative Records and Publications, 1979.0162.02438. -

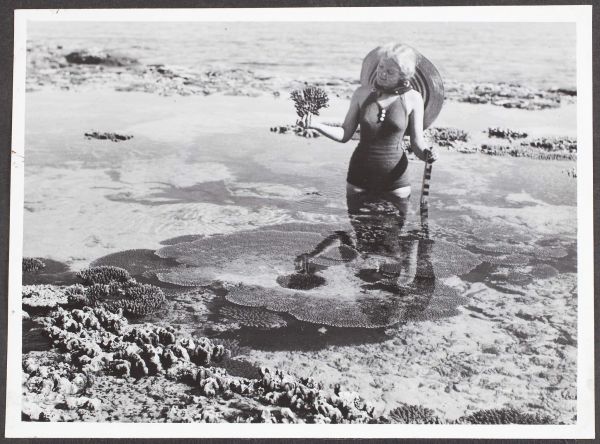

1979-0162-02560-00001.jpg

“Coral Pool, Heron Island, Great Barrier Reef, QLD”, 1947, Commercial Travellers’ Association Administrative Records and Publications, 1979.0162.02560. -

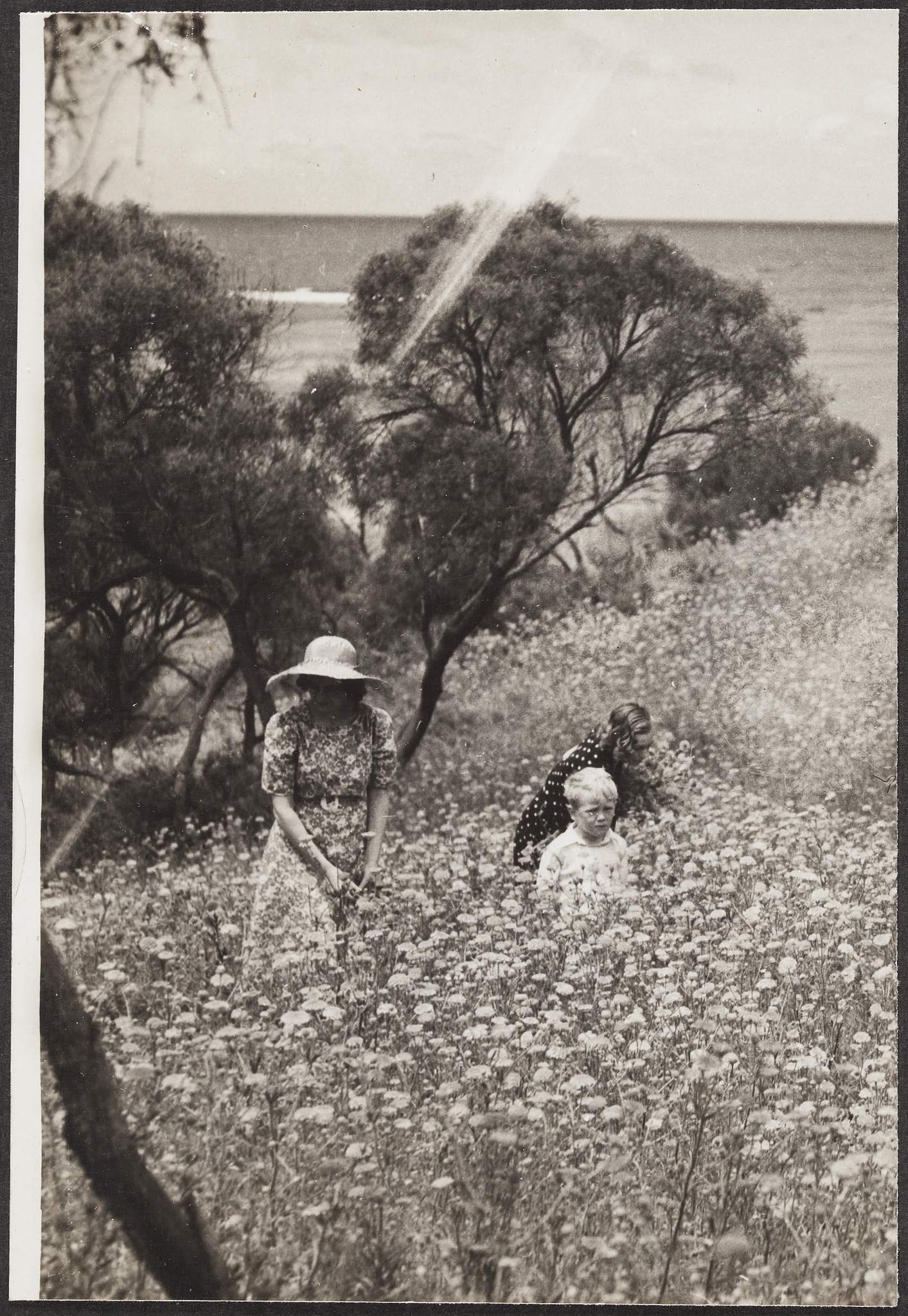

1979-0162-02505-00001.jpg

“Woman and children at Rottnest Island< WA”, c.1920-1950, Commercial Travellers’ Association, 1979.0162.02505. -

1979-0162-02644-00001.jpg

“Woman with blossoms, Canberra, ACT”, 8 August 1951, Commercial Travellers’ Association Administrative Records and Publications, 1979.0162.02644.

Footnotes

[i] Ronald McNicoll, “Riddell, John Carre (1809–1879)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1976.

[ii] G. F. James, 'Joyce, Alfred (1821–1901)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1967.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] "Family Notices", Argus 24 July 1915: 11 .

[v] For copies of The Traveller see Commercial Traveller’s Association Administration Records, Publications and Objects, 2014.0018 Unit 37;

World War Two: Refugees, Displaced Persons, and Community

Asta Ohr is employed as a

“porterette” on the South Australian Railways”

26 September 1949

Commercial Travellers Association Administrative Records and Publications

1979.0162.03133.

In the aftermath of World War Two, Australia’s response to the refugee crisis was shaped by the pragmatic imperative of importing labour to grow the Australian economy. In 1947, Australia signed an agreement with the United Nations International Refugee Organization (formed 1946) to take four thousand displaced persons.[i]

Under immigration minister Arthur Calwell this initial resettlement program was extended by the 1951 agreement with Italy and 1952 agreement with Greece, and as a result, throughout the program’s duration, Australia received 170 000 Displaced Persons. As immigration historian James Jupp stated, while these agreements ‘laid the foundations for a multicultural Australia’, they also occurred at the historical moment when the immigrant proportion of the Australian population was its lowest since 1930, therefore exemplifying the contemporary rhetoric of “populate or perish.”[ii]

The first Displaced Persons settled in Australians were from Baltic countries – those thought to be “closer” to British people within the racialised worldview of Australia’s Immigration Restriction Act.

Australia’s exclusionary immigration policies which had tightened in the 1930s climate of persecution and marginalisation in Europe were challenged by individuals and groups in response to World War Two and the Holocaust. Two prominent community activists for refugees and the Australian Jewish community were Mina and Leo Finks (1990.0091).

Miriam (Mina) Waks was born in 1913 in Bialystok, Poland. Orphaned as a young child, she was raised by her grandparents and matriculated in 1932. In that same year, Mina married Leo Fink and emigrated to Australia to join him. Leo Fink (1901-1972) had previously studied engineering in Germany before emigrating to Australia and starting with his brothers United Woollen Mills Pty Ltd and United Carpet Mills Pty Ltd.[iii] This pattern of “chain migration” in which multiple members of the same family migrate to the same place characterises not only the growth of the Bialystok community in Melbourne but more generally Australia’s immigration history. [iv]

The Bialystok ghetto was established in July 1941, cutting lines of correspondence and communication between families, like the Finks, who were desperate to know the fate of their relatives.[v] The Red Cross missing, wounded and prisoner of war enquiry cards collection contain a request for information in October 1942 possibly from the Fink Family:

seeking POLISH JEWS

26/10/1942: “Enq. From Vic. Re Wel and whereabouts. Mother – Polish Jewess born same town aged about 54 years. Father, Pincahs Fink, Polish Jew, born same town aged about 55 years. He was textile mechanic. Brother Szmul 26 years in Polish Mechanised army place cabled re the above & family

2-11-42: Cable BG301 to Geneva req. Enq.”[vi]

For more information on the Red Cross computer system see the subject guide <Early Computing> and Fiona Ross, ‘‘A Humane and Intimate Administration’: The Red Cross’ World War Two Wounded, Missing and Prisoner of War Cards’, The University of Melbourne Archives Blog, 10 May 2017.

It was during this period of personal and community tragedy and crisis that Leo and Mina became leaders in many Jewish community organisations. The collection contains correspondence, publications, and minutes relating to Mina and Leo’s various positions. From 1944 to 1947, Mina was president of the Ladies Group of the United Jewish Overseas Relief Fund which involved collecting and packing parcels of clothing and food for refugees and those affected by war.

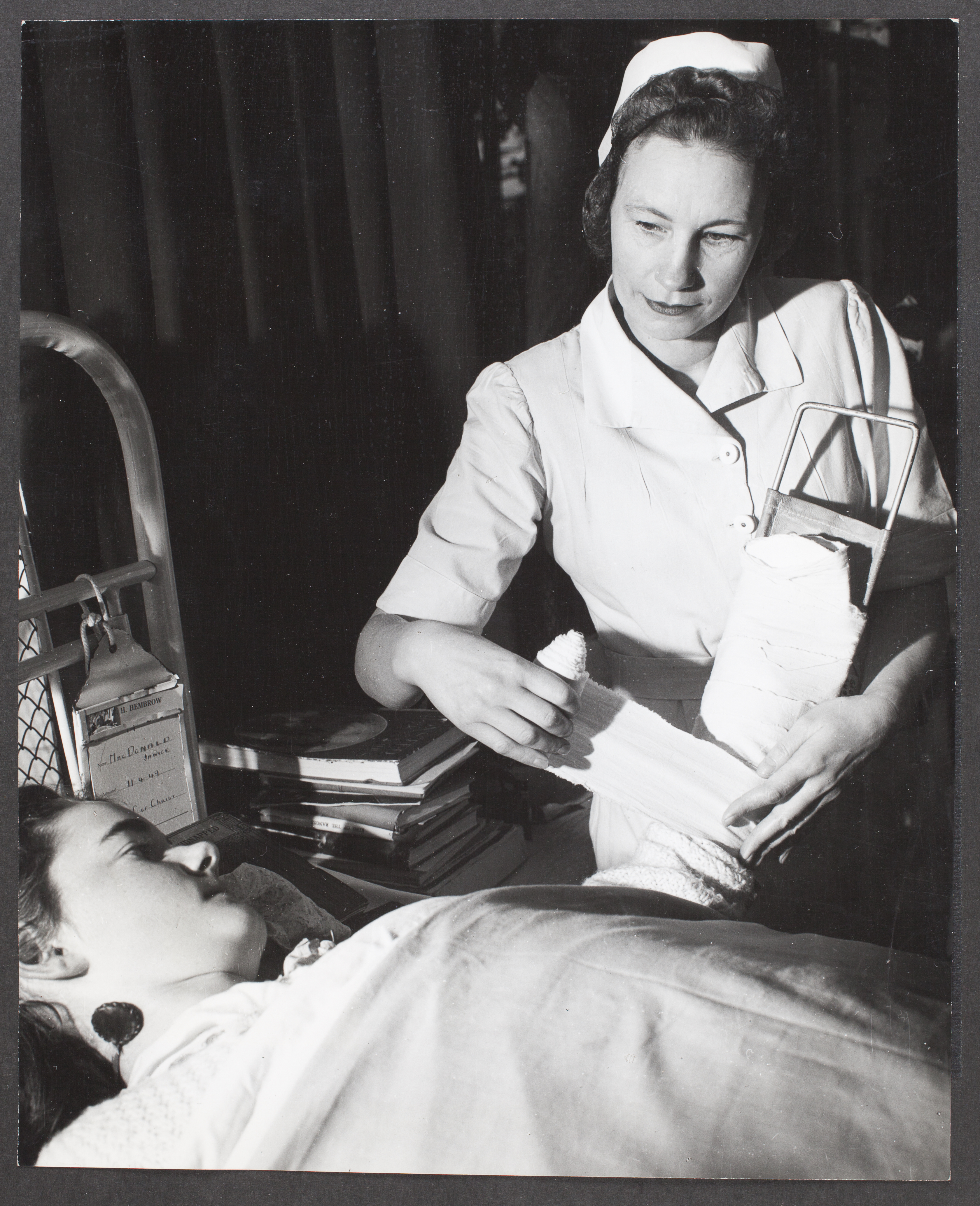

“Anna Sipols, former Latvian nurse,

now treats patients as a member on the nursing staff

of the Austin Hospital, Melbourne”

26 September 1949

Commercial Travellers’ Association Administrative Records and Publications

1979.0162.03136.

After World War Two, the United Jewish Overseas Relief Fund took over the Australian Jewish Welfare Society in Melbourne which had been established in 1937 and previously took a conservative position cohering with government immigration policy on questions of refugees.[vii] Suzanne Rutland has suggested that under Leo Fink’s leadership the renamed Australian Jewish Welfare and Relief Society (AJW&RS) was ‘prepared to bend the rules unlike its conservative Sydney counterpart’, and as a result 60 percent of Holocaust survivors settling in Australia were settled in Melbourne.[viii]

Of particular interest for the history of Jewish migration to Australia, is 1990.0091 Folder 8 which contains the Federation of Australian Jewish Welfare Society’s correspondence regarding their policy not to assist Jewish people in “mixed marriages” to immigrate to Australia (late 1940s - early 1950s).

As long-time director of the AAJW&RS (1947-1976) Mina helped to establish and run the AJWRS’s migrant hostels which provided reception and support for refugees, especially women and children. Mina’s generosity and commitment was exemplified by being a surrogate mother for a group of war orphans known as “the Buchenwald Boys.”[ix] Folder 9 contains details of the sponsorship of child migrants from Italy, while Folder 13 contains supporting documents written by the Finks to sponsor Italian migrants (undated), and 1946-7 correspondence with Jewish people in Shanghai.

At the same time, Mina was president of the National Council of Jewish Women Victorian Section (1958-1960) and National President (1958-1960), and a foundation member of Melbourne’s Holocaust Museum, for which Leo and Mina Fink Fund purchased the original building. One of Mina’s ongoing humanitarian and educational legacies is the training of Holocaust survivors as museum guides.[x]

For documents relating to the internment of refugees from Germany during World War Two see the Sophie Ducker 2000.0260 collection. Sophie Ducker née von Klemperer (1909-2004) studied botany in Geneva before her family fled Germany in 1938, moving first to Persia, briefly to Rodhesia where Ducker was employed as a governess and then to Australia. Ducker was interned at Tatura, located in Rushworth, Victoria. It was the first Australian purpose-built Internment Camp for World War II.[xi] Upon her release in 1944, Ducker became a technical assistant in the Botany department at the University of Melbourne under Dr Ethel McLennan (hyperlink to collections). She studied part-time to complete her Bachelor of Science, leading to her appointment as a Senior Demonstrator in 1953. Ducker had a special interest in marine biology which she was instrumental in introducing to the botany curriculum, and in her retirement carried out important research on sea-grasses.[xii] The collection 2000.0260 comprises news cuttings, refugee and internment documents.

Footnotes

[i]National Archives of Australia.

[ii] James Jupp, From White Australia to Woomera: The Story of Australian Immigration, second edition (Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 13.

Biographies: Leo Fink (1901-1972), Yiddish Melbourne, Monash University.

[iii] Jenny Wajsenberg, “Landsmanschaft Postscript: The Bialystoker Centre in Melbourne, Australia 1927–1977”, Holocaust Studies, 16:3, (2010): 61.

[iv] Wajsenberg, “ Landmandscaft Postscript”: 64.

[v] “Fink, Enucha & Family, [No Service Number]”, 26 October 1942, Red Cross Missing, Wounded and Prisoner of War Enquiry Cards, 2016.0049.17361.

[vi] Suzanne D. Rutland, “Resettling the Survivors of the Holocaust in Australia”, Holocaust Studies 16:3 (2010): 35.

[vii] Rutland, “Resettling the Survivors of the Holocaust in Australia”:36.

[viii] “Mina Fink”, Jewish Holocaust Centre.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] “Tatura, Rushworth (1940-1947)”, National Archives of Australia.

[xi] Sara Maroske, “Biographical Notes: Sophie Ducker (1909-2004)”, Council of Heads of Australasian Herbaria: Australian National Herbarium, September 2004.

Integration and Reception (1946-1960s)

Contemporary to the Chifley government agreements with the International Refugee Organization to settle Displaced Persons from Europe in Australia, in the early-1950s it established “Good Neighbour Councils” and “Australian Citizenship Conventions” to involve the Australian community in integrating “New Australians.”[i]

Aiming to spread “Australian values”, these associations were inextricably linked to the idea of assimilating migrants into a homogenising, British national narrative. Yet, on a person-to-person level, member organisations, such as the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), and their volunteers extended kindness and support to migrants; both those temporarily housed in camps and those forging new lives in Australia’s cities, suburbs, and towns.

The YWCA’s Immigration Regional Coordinating Committee Minutes 1947-Nov 1969 (1984.0066 Unit 107) outlines regional New South Wales and Victorian hostel conditions and standards, including reports of visits to migrant camps. Notably, discussion regarding the integration of migrants into the “Australian Way of Life” are prominent from 1959 onwards.

In 1963, the Young Women’s Christian Association in partnership with the Travellers Aid Society conducted an orientation course for young women from Greece on daily life in Australia, including excursions to banks and post offices (a report from 25th October 1963 is held in 1984.0066 Unit 107).

Unit 109 also contains the recollections of Dina Natzika, a young Greek-Australian entitled “My Life in Australia” (two pages, typed). She began by telling how:

‘This is our seventh year in Australia all of which have been the most happy anyone could wish for. I was only ten when we migrated from Greece and now at seventeen am in my last year of high school.’

‘Our family however may be said to be an exception for not all new Australians have adjusted the way we have. I think the reason behind this is the fact that when we left Greece we had no intention of returning whereas other families migrated with regret hoping to amass a sum of money in Australia and then return and spend it in their mother country.’

‘The greatest problem migrants are faced with is the new language. It is terribly hard for any adult, used as they are to their own, to suddenly change and learn a whole new language.’[ii]

Subsequent minutes of the National Immigration Committee from 7 June 1965 highlighted some of the challenges for recent migrant women in finding employment:

‘Mr Lotsoulas also raised the point of employment for Greek girls and said that he thought that the Immigration and Labour departments might have the wrong idea that girls were wanting domestic employment only, but girls are more interested in other work, and this idea was affecting their attitude before coming to Australia, and they are not anxious to come for domestic work.’ [iii]

Questions of integration seem to have acquired a civic language in the mid-1960s, reflecting an evolving Australian identity. Exemplifying this is the YWCA Minutes of the Meeting the National Immigration Committee Held at National Headquarters on 7 December 1964, in which one speaker at the Citizenship Convention themed “Every Settler a Citizen” controversially stated:

‘One reason for non-naturalisation is the question of loyalty to the Queen of England. Lack of understanding the Commonwealth and its loyalty. Migrants would be prepared for loyalty to the Queen of Australia.’ [iv]

The minutes of a later meeting on 15 November 1965 portray the role of the YWCA in providing education and community resources to Australia’s migrant camps. One member, Mrs Crawford reported on improved conditions in migrant camps – ‘hut is now very satisfactory, after years of battling against poor conditions – and the YWCA’s role in providing resources like children’s libraries and art exhibitions.[v]

See also the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union 2010.0016 Unit 15 for files relating to the Union’s “Friendship to Migrants” initiatives from 1968 to 1995.

Footnotes

[i] Gwenda Tavan, ‘“Good neighbours’: Community organisations, migrant assimilation and Australian society and culture, 1950–1961”, Australian Historical Studies 27:109, (1997): 78.

[ii] All quotes are from Dina Natzika, “My Life in Australia”, undated Young Women’s Christian Association, 1984.0066 Unit 109, p1.

[iii] Young Women’s Christian Association, “Minutes of the Meeting of the National Immigration Committee Held at National Headquarters,” 7 June 1965, 1984.0066, Unit 107, p1.

[iv] Youvg Women’s Christian Association, “Minutes of the Meeting of the National Immigration Committee Held at National Headquarters,” 7 December 1964, 1984.0066, Unit 107, p3.

Exclusion to Multiculturalism

Challenging the White Australia Policy

Australia’s racialised and exclusionary immigration policies under the Immigration Restriction Act (1901), commonly known as the White Australia Policy were incrementally dismantled in the post-World War Two era. In 1957 the Menzies government introduced reforms allowing non-European migrants to be eligible for citizenship after fifteen years of residence, followed by the abolition of one of the most notorious emblems of the White Australia Policy, the dictation test, in 1958. Significantly, the Migration Act (1966) established legal equality between British, European and non-European migrants, defining suitability for migration on purely one’s potential to contribute (economically) to Australia.[i] Largely symbolic, the Whitlam government’s formal abolition of the Immigration Restriction Act in 1973 was accompanied by a philosophical shift from assimilation to multiculturalism.

Yet, outside of this government-centric narrative, civil society activism played a significant role in changing Australian attitudes towards migration and race. Files relating to one prominent activist group, the Immigration Reform Group, and its member Mary Tait are held in the University of Melbourne Archives.

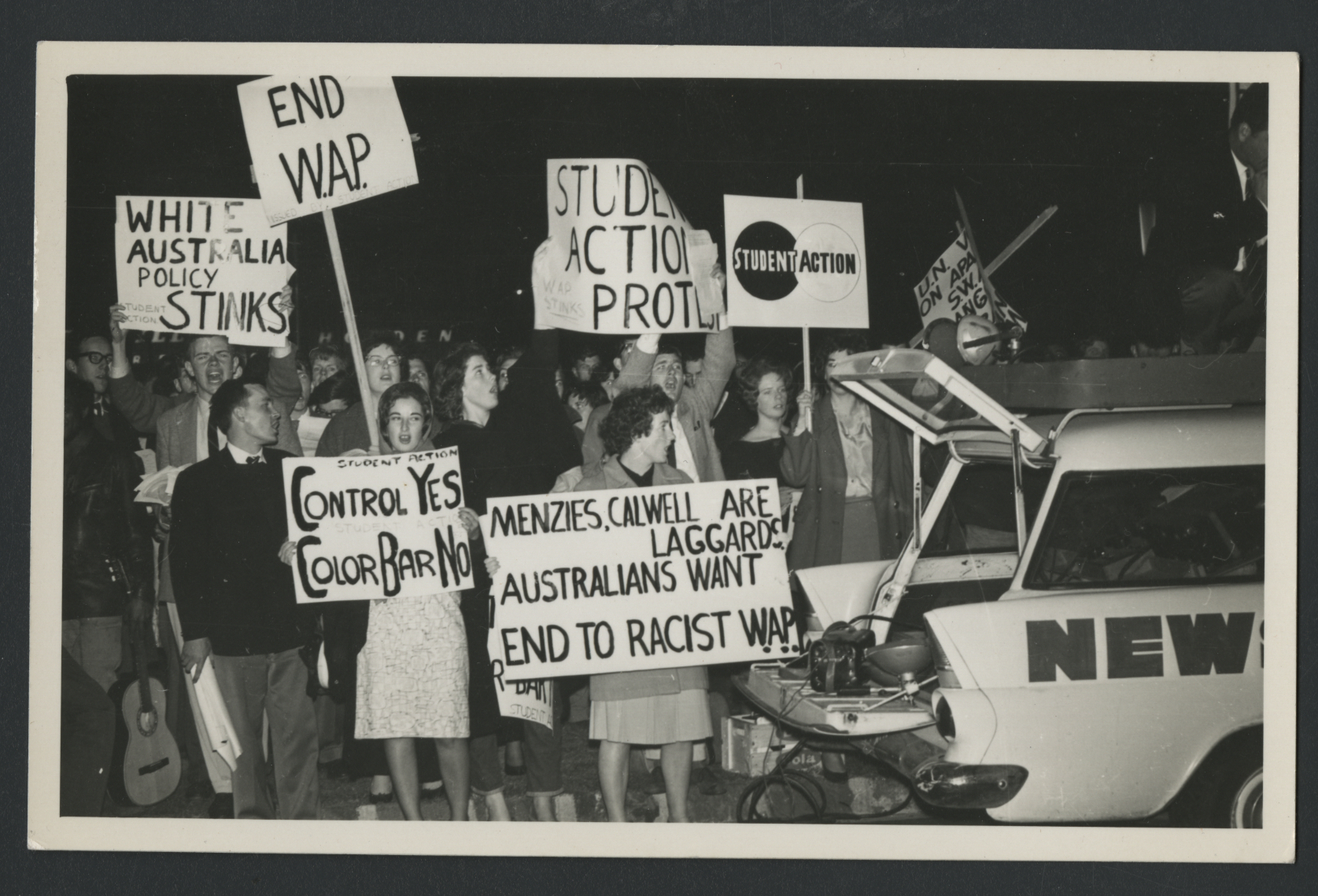

Front Row: John Johnson (President, Student Action - also involved in WUS). Rosie Thomas with poster

"Control YES. Colour Bar NO."

“Student Action campaign against the White Australian [sic] Policy during the 1961 Federal Election”,

2013.0047.00004.

Studying Arts from 1955 to 1958 at the University of Melbourne, Mary Tait née Young became a leader in student activism, particularly the National Union of Australian University Students (NUAUS) and pursued her interest in Asia. The collection 2016.0132 contains files relating to her interest in India, including the student delegation to India in early 1959, Indonesian Student Delegation to Australia (1959) and returning to study Social Work at the University of Melbourne in 1959-1960.

Mary was appointed the Travelling Secretary for the Australian Committee of the World University Service and the collection contains student protest materials condemning apartheid. Following a period studying in India (1962-1964), Mary became head of the the Australia-Overseas Travel Scheme (1964-5) for the National Union of Australian University Students (NUAUS)..

Mary’s involvement with the Immigration Reform Group started in 1959 following the receiving of a circular from J.A.C Mackie, Senior Lecturer in Indonesian Studies at the University of Melbourne, dated 6 May 1959 (held in 2013.0026). This circular, sent to thirty intellectuals, organisations, and church representatives outlined the groups’ foundational aim to be:

‘a small active study-group which will go into various aspects of present and proposed immigration policies thoroughly before it attempts to formulate positive recommendations or to launch any proselytising campaign.’

The same circular also highlighted Australia’s increasing diversity could not be separated from insular social attitudes and prejudice:

‘There is no ground for optimism in what little we know about attitudes to migrants and “foreigners” generally in the social strata which feel most threatened by competition from them. Recent British experience shows how even a remarkably tolerant society may include pockets of violent racial prejudice.’

The Immigration Reform Group collection (2013.0026) also includes a two-page handwritten draft of Mary Tait’s 1959 speech which reflected upon the changes under the 1958 Immigration Act, especially the granting of ministerial discretion to cases of political asylum, and Australian and non-European marriages, as destabilising Australia’s White Australia Policy.

‘Although our wall of exclusion is being gradually chipped away there seems a need for someone to put a stuck or two of dynamite under it.’ [ii]

She strongly critiqued the ‘wall of exclusion’ and ‘our morally unjustified policy’, asserting that there: ‘seems to be no case at all for excluding Asiatics (or Africans) from Australia merely because they happen to be dark-skinned, or come from economically underdeveloped countries.’ [iii] Concluding, Mary predicted that while Australia may define its criteria for immigrants on education, good health, and their potential economic benefit, there would soon be a more global, integrated approach to people movement:

‘In time, emigration and immigration might be organized throughout the world by the United Nations so that bitterness is eliminated & the needs of all countries are balanced.’[iv]

The Immigration Reform’s Group’s 1960 critique of the White Australia policy titled Control or Colour Bar sold eight thousand copies and ignited debate regarding the morality of exclusionary immigration policies.[v] A digitised copy of Control or Colour Bar is available on the State Library of Victoria website, refer to: In its conclusion, the Immigration Reform group outlined nine pressing reforms:

- The public announcement of the White Australia Policy’s end;

- Social and economic factors being the ‘sole determinant of our intake’;

- Trial five-year period for non-Europeans to settle in Australia;

- Reform to take place after this trial;

- Close relatives of those already settled to gain priority;

- Bilateral agreements;

- Even male and female intakes;

- Non-European migrants held to same health and security standards as Europeans;

- That ‘wise selection and legal equality on arrival are the only two aspects of a prudent immigration policy.’[vi]

The collection 2013.0026 also contains reports regarding the Immigration Reform Group’s second and third meetings; agendas for the Study Group on the White Australia Policy; a summary of current legislation by Howard Nathan, and handwritten notes by Mary Tait.

On 19 June 2013, Professor Kate Darian-Smith facilitated a “witness seminar” at the University of Melbourne to discuss the Immigration Reform Group’s legacy. As a “witness seminar” this event aimed to augment the existing historical record on the Immigration Reform Group by involving participants The Hon. Mr Stephen Charles QC, Associate-Professor Charles Coppel, Sir James Gobbo QC, Alan Gregory, The Hon. Howard Nathan, and Ailsa Zainu’ddin. The University of Melbourne Archives, as custodians of this history holds digitised recordings of this seminar:

Multiculturalism (1975-)

Accompanying the formal dismantling of the Immigration Restriction Act by the Whitlam government, multiculturalism became the basis of an emerging modern Australian identity. Reflecting a focus on understanding particular challenges for especially non-English as a first language speakers, the Trade Union Migrant Workers’ Centre (2001.0027) was established in 1976, aiming to strengthen ties between linguistically and culturally diverse workers and the union movement.

Unit 8 files 82, 84-86 cover a variety of women’s issues in the workplace, including initiatives for education and health (Some restrictions apply to files containing clientele information, please contact the UMA).

According to Sylvia Panayis’ report titled “Migrant Women Workers” from the Trade Union Migrant Workers’ Centre, possibly in the early 1980s, upholding workplace safety standards and workers’ rights remained a major challenge. This report is held in the Council of Action for Equal Pay 2000.0147 folder labelled “Archival Material”. Panayis’ research suggested that migrant women made up the vast majority of workers in the meat and food production, chemical and metal, and boot manufacturing industries. Specifically, compared to only 9.2% of Australian-born women, 45% of Italian-born, 56% of Greek-born and 54% of Yugoslav-born women in Australia worked in the aforementioned occupations.[vii]

These women carried out repetitive work within highly regimented workplaces with limited breaks and high occupational health and safety risks.[viii] The Trade Union Migrant Workers’ Centre suggested five recommendations: teaching of English on the job without resulting in pay losses; provision of multilingual health and safety information; establishment of childcare facilities; union organised courses for migrant women workers; and the abolition of jobs which caused repetitive strain injuries.[ix]

Similarly, the Women’s Legal Resource Group collection (2000.0230) contains correspondence and files from the Migrant Women’s Centre concerning a legal education scheme and the establishment of a small support group (minutes from the 26-28 September 1984). Project Worker Irena Orlowski, a lawyer originating from Poland, on 18 June 1984, described the project as aiming to ‘develop a useful legal support network and referral system for migrant women.’[x]

Two of the central challenges which the support group identified at the open meeting of 26-28 September 1984 were language and cultural barriers, and prior encounters with the law in migrants’ country of origin:

‘Migrant experiences of oppression and p[o]lice power in their own country, illustrated much of this fear and hatred also due to lack of familiarity with Australian culture.’

Other collections relating to women and multiculturalism include Ada May Norris née Bickford (1990.0109). Ada completed her Bachelor of Arts and Diploma in Education in 1924 at the University of Melbourne and Master of Arts in 1926 before becoming a school teacher at Leongatha and Melbourne High schools.[xi] From the 1930s until her death in 1990, Ada was committed to a range of causes, particularly disability, children, aging, and immigration. She was appointed convenor of Victoria and Australia’s National Council of Women’s Migration Standing Committee in 1952, and was a prominent member of the Good Neighbour Council of Victoria.[xii] As a member of the International Council of Women’s executive committee (1966-78) she worked as convener on migration and became committed to international women’s rights and campaigning for Australian leadership internationally on gender issues.[xiii]

The extensive collection of papers held by the University of Melbourne archives contains documents –minutes, newsletters, correspondence, and speeches – from the numerous organisations which Ada supported and contributed. Of particular note for women and multiculturalism are the agendas and minutes from the Australian Ethnic Affairs Council in 1990.0109.

For a glimpse into multicultural art and the politics of Australia’s bicentenary refer to Susy Pinchen’s multicultural art project “A Bitter Song” (1991.0045). Organised during 1985 and 1986 under the working title “3 Cities, 3 Cultures”. Files include correspondence between multiple funding bodies and its creator, a copy of Vogue’s Bicentennial Arts Guide, and reviews of the project which, after funding complications, took place in Melbourne and Adelaide.

Footnotes

[i] Young Women’s Christian Association, “Minutes of the Meeting of the National Immigration Committee Held at National Headquarters,” 7 December 1964, 1984.0066, Unit 107, p3.

[ii] Young Women’s Christian Association, “Minutes of the Meeting of the National Immigration Committee Held at National Headquarters,” 15 November 1965, 1984.0066, Unit 107, p2.

[iii] National Museum of Australia, “White Australia policy ends”, Defining Moments in Australian History.

[iv] “Untitled speech of Mary Tait to Study Group”, 1959, 2013.0026, p1.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid., p2.

[vii] Jacqueline Templeton, “Immigration Reform Group”, eMelbourne, School of Historical & Philosophical Studies, The University of Melbourne, July 2008.

[viii] The Immigration Reform Group, Control or Colour Bar (Melbourne: The Immigration Reform Group: 1960), accessed online State Library of Victoria, p.47-48.

[ix] Sylvia Panayis, “Migrant Women Workers” Trade Union Migrant Workers’ Centre, Council of Action for Equal Pay, 2000.0147, p1.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid. p2.

[xii] “Minutes from Migrant Women’s Centre 26-28 September 1984”, Women’s Legal Resource Group, 2000.0230, p1.

[xiii] Margaret Fitzherbert, “Norris, Dame Ada May (1901–1989)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 2012.

[xiv] Jane Carey and Anne Heywood, “Norris, Dame Ada May (1901-1989)”, Australian Women’s Register, 12 September 2017.

[xv] Fitzherbert,” Norris, Dame Ada May”.