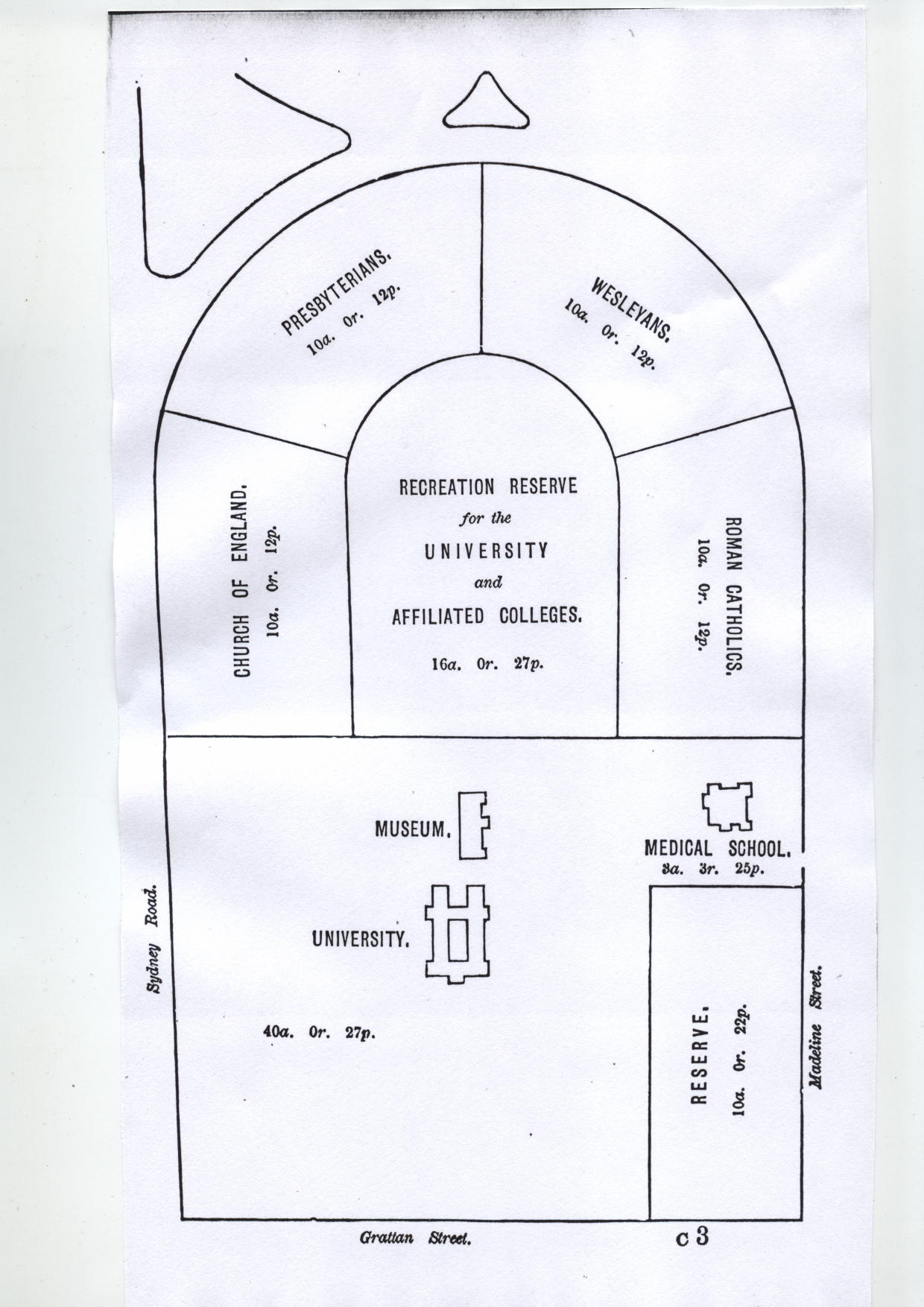

Key 16: The University Colleges 1861; 1870; 1879; 1887; 1916

Although the University of Melbourne was not established on the collegiate model of Oxford and Cambridge, there was a clear expectation that colleges would be built within the grounds to provide supervised residence and some additional tuition. Hope that individual benefactors might come forward soon faded and it became clear that only the churches had the necessary inclination and resources. In 1861, as envious eyes from within the rapidly encroaching suburbs were cast towards the vacant land to the north of the University buildings, the four major Christian denominations were granted a little over 10 acres each. The sixteen acres left in the centre of this area was set aside as a recreation ground.

[Source: University of Melbourne, Calendar 1877-78, p. 33]

In 1870 the foundation stone was laid for the Anglican Trinity College facing Sydney Road [Royal Parade] and students were in residence by 1872. It was formally affiliated with the University in 1876, when Alexander G. Leeper became Warden, a position he held until 1918.

[Source: University of Melbourne Archives Image Catalogue, UMA-I-977]

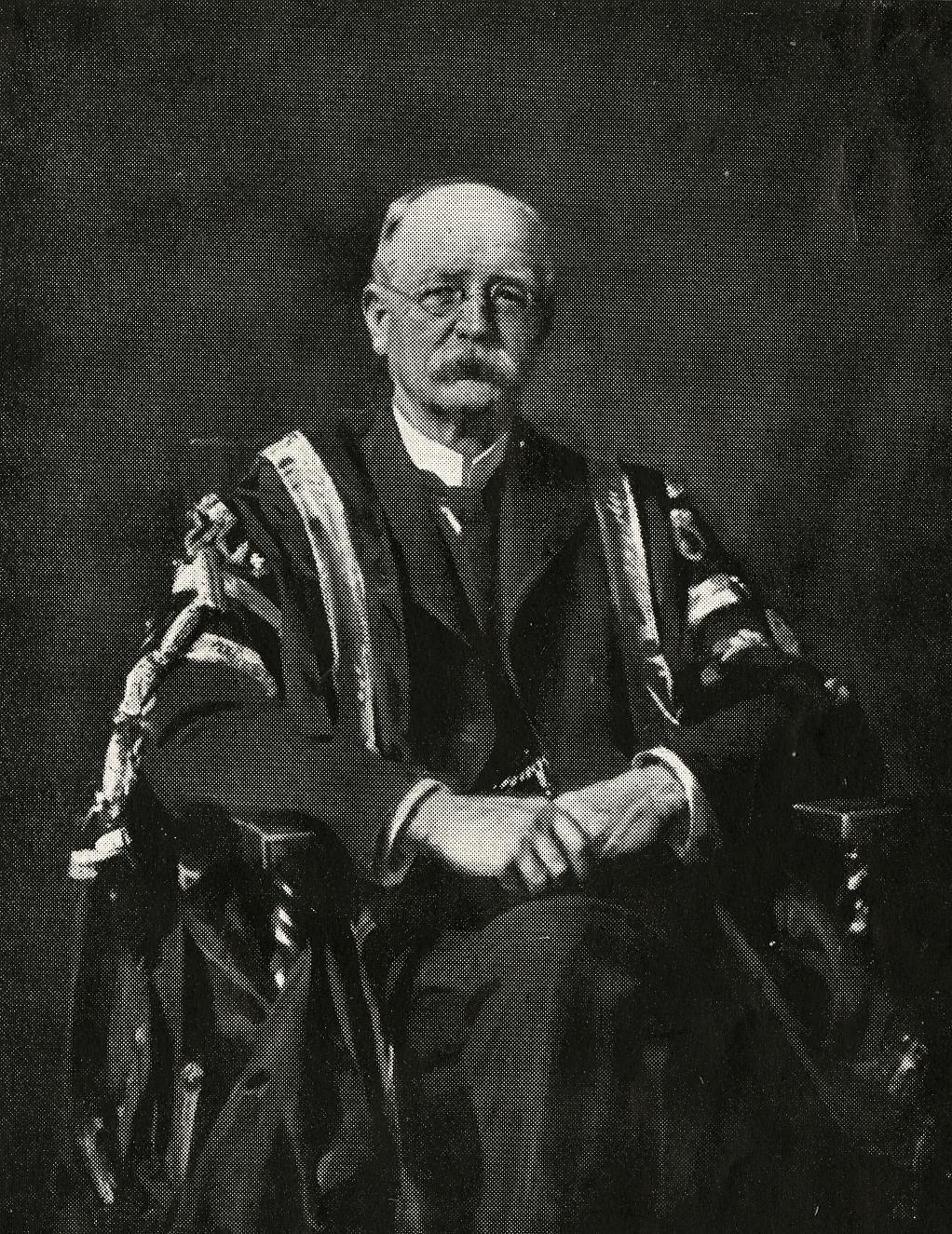

The Presbyterian College on the north west arc of College Crescent, named for its principal benefactor Francis Ormond, was founded in 1879. The first Master was [Sir]John MacFarland 1881-1914 (later Vice-Chancellor 1914-1918, and Chancellor 1918-1935) followed by D.K. Picken.

[Source: University of Melbourne Archives Image Catalogue, UMA-I-1446]

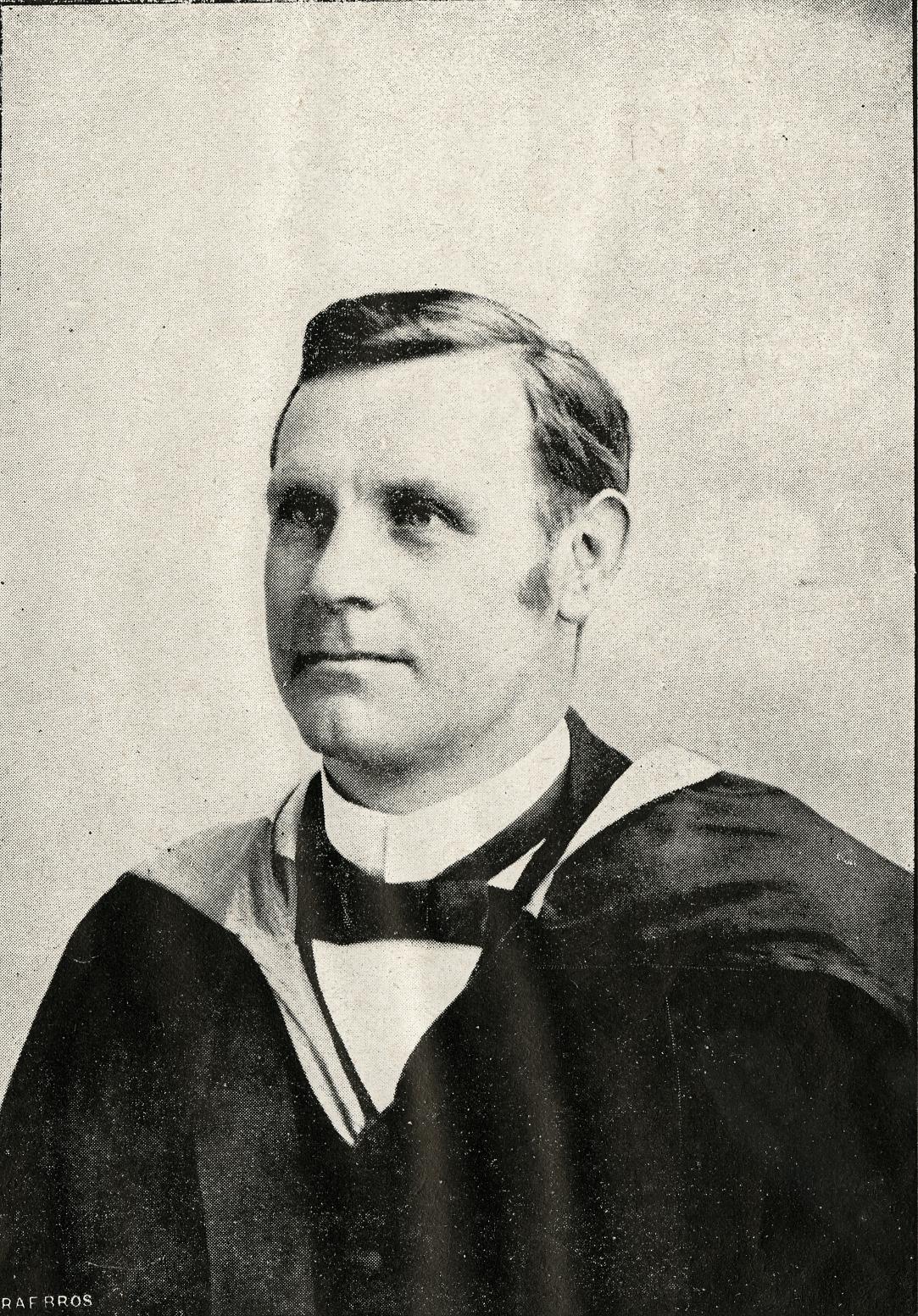

The Wesleyan Methodist Church named its college situated on the north east arc 'Queen's' since the foundation stone was laid in 1887, the jubilee year of Queen Victoria’s reign, E.H. Sugden holding the Master's position 1888-1928.

[Source: University of Melbourne Archives Image Catalogue, UMA-I-1021]

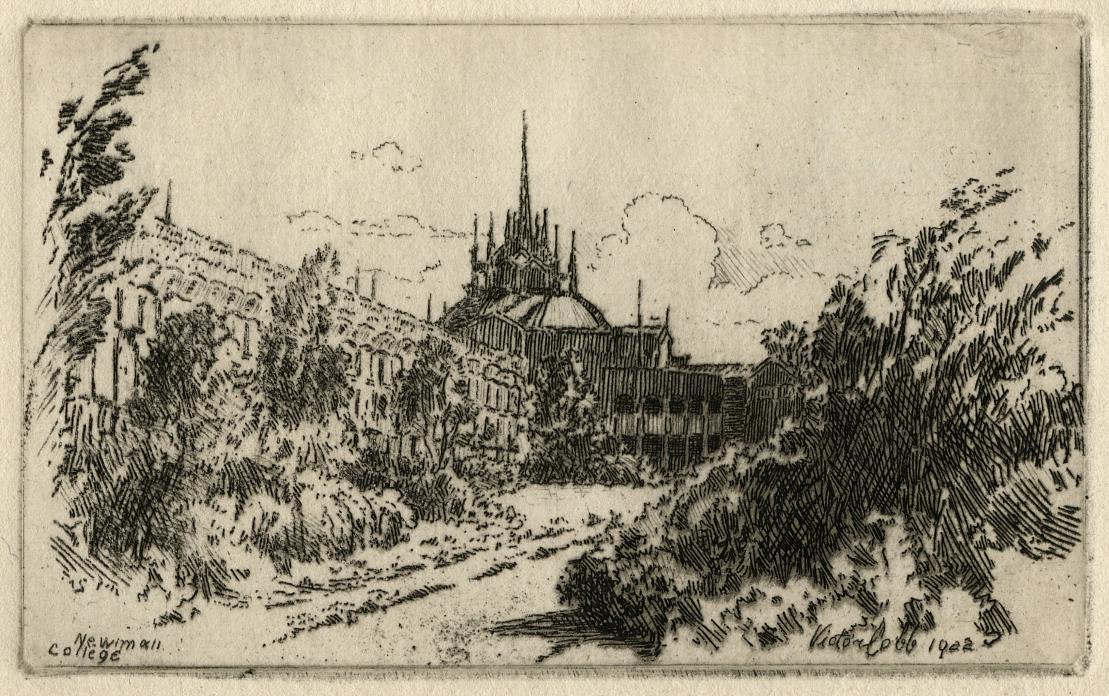

The Roman Catholic Newman College, facing Swanston Street, was not begun until 1916, largely because the Church felt that the establishment of a comprehensive school system at primary and secondary levels should take precedence. The offer from Sydney Catholic, Thomas Donovan of £30,000 for student bursaries provided a college was built proved sufficient encouragement - and the requisite money was easily raised. Newman College, named for the famous Cardinal whose discourse on The Idea of a University had not lost its eloquent appeal, broke new ground in architectural terms in turning its back on the Gothic. The design by Walter Burley Griffin, the innovative American architect who with Marion Mahony Griffin laid out the design for the nation’s federal capital in Canberra, provided superior accommodation to any other college in Australia, and remains a treasure of twentieth century architecture in Australia. Its first head was The Very Rev. James O'Dwyer.

[Source: University of Melbourne Archives Image Catalogue, UMA-I-1284]

The churches were initially slow to take up the offer of land for colleges because the Government insisted on an active role in their governance. It was not until 1869 that the compromise which gave the university the advantages of both denominational and secular education was reached. The colleges were also able to incorporate the theological studies which could not be taught in the strictly secular University curriculum. After a slow start in attracting students a vigorous community life developed in the colleges in the 1880s, and for many decades, these, rather than the University attracted the loyalty, pride and philanthropy of the students.

Until well into the twentieth century the Colleges played a substantial role in the life of the University. In many respects their heads had more influence than the professors. Together with members of their governing bodies they sat as members of the University Council which invariably included active sympathisers among the other members. College students both resident and non-resident were among the academically strongest and the most active in university life generally.

[Source: University of Melbourne Archives Image Catalogue, UMA-I-1247]

In the case of J.H. MacFarland, influence was translated into real power as he progressed from Master of Ormond College (1881-1914) to Vice Chancellor (1914-1918) and finally Chancellor from 1918 until his death in 1935. Blainey suggests that 'the rise of the Melbourne colleges' had 'no parallel in the new universities of the British Empire in the second half of the last century.' Much of the explanation lies in the quality of leadership of the first three colleges. During long reigns A.G. Leeper, J.H. MacFarland and E.H. Sugden developed a vigorous tutorial system while successfully courting wealthy churchmen, especially 'wealthy God-fearing pastoralists who believed that the church colleges were more deserving than the university itself. Without their bequests the colleges would have remained small.'

[Source: University of Melbourne Archives Image Catalogue, UMA-I-1922]

[Source: University of Melbourne Archives Image Catalogue, UMA-I-1387]

Geoffrey Blainey goes so far as to suggest that their influence on much of the university's talent exceeded that of the university’s most influential professors.