Melbourne Architecture

Melbourne Architecture

Exhibition

Original plans, photographs and documents for ten special buildings in Melbourne illustrate a range of resources held by the University of Melbourne Archives.

These ten buildings were featured in the Open House Melbourne program and in an exhibition as part of the University’s Cultural Treasures Festival in 2012.

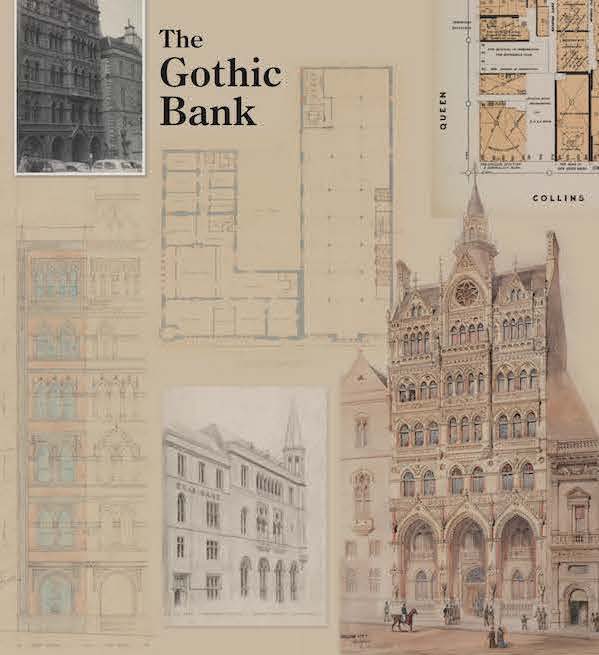

The Gothic Bank

The Gothic Bank is the central building in a complex on the corner of Collins and Queen streets, now housing the ANZ bank. The Gothic bank was built in Gothic Revival style for the English, Scottish and Australian Chartered Bank (ES & A) in 1883-87. Designed by William Wardell and commissioned by ES & A general manager Sir George Verdon, the building included a residence for Verdon over two floors above the business. The interiors of both the bank and residence were lavish, as befits a thriving bank in a booming economy.

The buildings either side of the Gothic Bank were both designed by William Pitt and both are linked to land speculator and local personality, Benjamin Fink. Fink sold his land in Queen Street to the Stock Exchange for the Safe Deposit Building project while he was Chairman of the Exchange. The Stock Exchange Building (1890) on Collins Street was an extravagant project and its costs far exceeded the resources of the Exchange, resulting in its sale to the ES & A in the 1923. The Safe Deposit building (1891) is a more restrained interpretation of the Gothic Revival style, built in brick with cement details rather than the more flamboyant sandstone and marble of the Exchange. The Safe Deposit building was the home of The Automobile Club in 1924, at the time the ES & A extended eastwards as seen on a section of city map, shown above. In this year an additional wing was added to the Safe Deposit building and eventually this too became part of the ES & A bank.

Successor to the ES & A, the Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd, undertook restoration and redevelopment of the whole site in 1990-93, building a modern office tower at the rear, connected to the other buildings by a glass-roofed atrium.

E S & A bank (Gothic Bank)

Photograph of Safe Deposit Building, with ES & A beyond, undated

Photographer unknown

Stephenson & Turner 1985.0072

Alterations & Addition, ES & A Bank, Second Floor Plan, sheet number 5, 1922,

showing house quarters as well as works in old stock exchange building

John & Herwald. G. Kirkpatrick, architect and consulting engineers

Clements Langford Pty Ltd 1960.0003

Sketch of the ES & Bank, undated

Pencil on tracing paper

Stephenson & Turner 1985.0072

Map showing corner of Queen and Collins Streets, 1924

Sheet 14 (box 4)

G Mahlstedt & Son 1961.0017

Stock Exchange Building

Elevation, Stock Exchange Building, 1890

Architect, William Pitt

Stock Exchange of Melbourne 1968.0018

Safe Deposit Building

Photograph of Safe Deposit Building, with ES & A beyond, undated

Photographer unknown

Stephenson & Turner 1985.0072

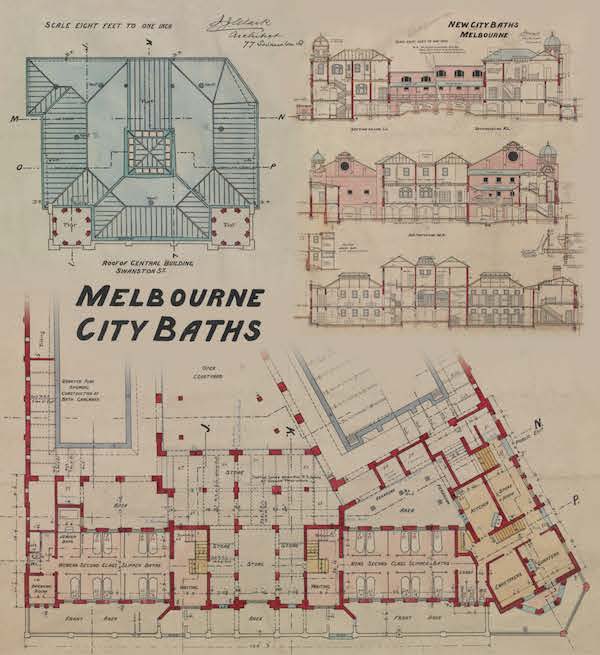

Melbourne City Baths

Separate entrances for men and women can still be seen on the façade of the Melbourne City Baths, but many other details of this building have changed since its opening in 1904. At that time, the majority of Melbourne’s population did not bathe at home - the Baths were as much about cleanliness and public health as exercise or recreation. Plans for the building by JJ Clark show that all facilities were segregated. A swimming pool, 16 slipper baths, six spray baths and a gymnasium were provided for men and another pool and baths were provided for women. There were also Turkish and vapour baths, a Jewish ceremonial bath and a laundry. Class distinctions were apparent with second class facilities in the basement and first class on the floor above.

Melbourne was known as ‘Smellbourne’ in the late 19th century as water and waste management systems struggled to keep pace with the rapid expansion of population following the gold rushes and in the boom that followed. The 1904 Melbourne City Baths complex replaced facilities opened in 1860.

Facilities began to fall into disrepair in the 1930s due to economic constraints and then due to reduction in numbers of people living in Melbourne’s inner areas, and by the 1970s the building was threatened by closure and demolition. This threat averted, the distinctive building was refurbished in the 1980s and today provides facilities for a city population that is expanding again.

Melbourne City Baths

Details of second-class facilities, from drawing number 2

Melbourne City Baths, 1904

Ink and watercolour with pencil annotations, on paper backed with linen

Architect: JJ Clark

JJ and EJ Clark 1981.0089.00014

Details of roof, from drawing number 4

Melbourne City Baths, 1904

Ink and watercolour with pencil annotations, on paper backed with linen

Architect: JJ Clark

JJ and EJ Clark 1981.0089.00020

Section drawings, drawing number 7

Melbourne City Baths, 1904

Ink and watercolour with pencil annotations, on paper backed with linen

Architect: JJ Clark

JJ and EJ Clark 1981.0089.00025

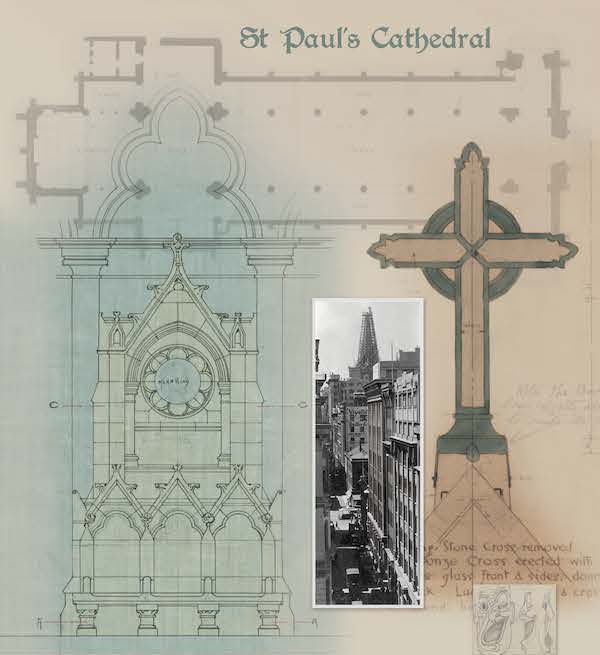

St Paul's Cathedral

From 1837, interdenominational church services in the colony of Port Phillip were held in a wooden building on the corner of William and Little Collins Streets. Various denominations soon established separate sites and made plans for more permanent buildings while the Church of England remained on this site. In 1839, work began on a stone building designed by Robert Russell, and in 1847, with the arrival of Bishop Perry, this church became the Cathedral for the See of Melbourne.

In 1884, a parish church of St Paul that had stood on the site of the first open air services on the corner of Swanston St was demolished to make way for a grand Cathedral. When the cathedral opened in 1891, St James’ reverted to a parish church. This church was moved stone by stone in 1913-14 to its present site on King St.

There have been many contributors to this Melbourne landmark. English architect William Butterfield designed the cathedral but never visited Melbourne so architects Terry and Oakden and later Joseph Reed supervised works by builders, Clements Langford. Following the resignation of Butterfield, Reed re-designed the Cathedral Offices and Chapter House. Over the years, countless artists, suppliers and trades have played their part to build St Paul’s. In 1926, Sydney architect John Barr re-designed the spires that completed the original project. While the Cathedral may look like a nineteenth century building, additions and alterations have been made to meet changing requirements and incorporate contemporary technologies. For example, gas lights have been replaced by electric ones; an illuminated cross was erected in the 1928; ramp access has been put in place and specialised audio equipment has been installed.

Plan of Cathedral, undated

Ink on glazed linen

Architect, William Butterfield

Bates Smart McCutcheon 1968.0013 (Job 295)

Proposed sedilia, undated

Ink and watercolour on glazed linen

Artist unknown, possibly William Howitt (c1846-1928)

Bates Smart McCutcheon 1968.0013 (Job 295)

Sketch of a gargoyle, undated

Pencil on the reverse of service sheet for 31 January 1932

Artist unknown

Clements Langford Pty Ltd 1960.0003

Spires of St Paul’s Cathedral under construction, October 1931

Photographer, Russell Grimwade

UMA/I/3304 (PA 45 p11)

Wilfrid Russell Grimwade 2002.0003.00649

Design for an illuminated cross for front gable, 1926

Watercolour & ink on paper with pencil annotations

Architect, John Barr

Contract document, 1928

Clements Langford Pty Ltd 1960.0003

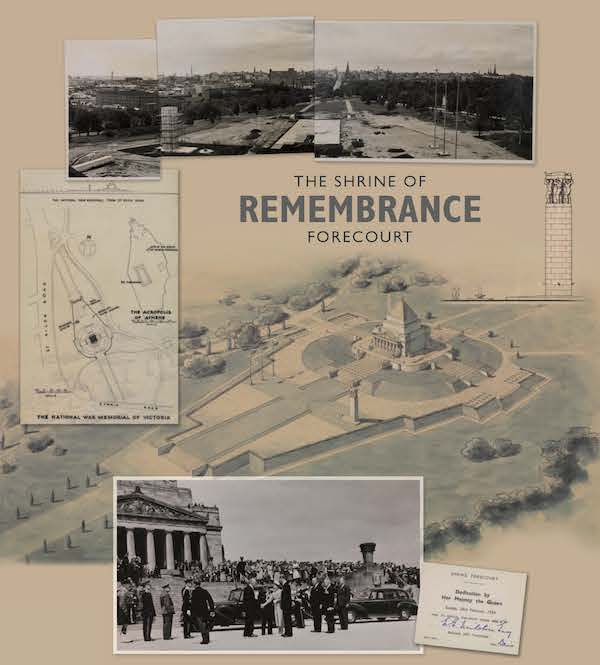

The Shrine of Remembrance

Victoria’s monument to those who served in the second world war was designed by a man whose personal experience of that war brought him to Australia. Born in Czechoslovakia in 1893, Arnost Edward Mühlstein established his architectural practice in the modernist style and travelled widely in Europe to study architecture of all periods. Mühlstein was Jewish – warned of his impending arrest, he fled Czechoslovakia in 1939.

Arriving in Adelaide in 1940, Mühlstein joined the practice of Lawson & Cheesman and began to settle in a new city, taking an active role in local theatre. He enlisted as a ‘friendly alien’ with the Royal Australian Engineers, which brought him to Melbourne in 1945. At the end of the war he remained in Victoria, acquired Australian citizenship and anglicised his name to Ernest Edward Milston.

Following WWII, the Trustees of the Shrine of Remembrance sought concepts for a memorial to complement the WWI Shrine of Remembrance. Two architects proposed a forecourt with EE Milston’s design selected. Both the Shrine and the Forecourt have classical roots, with the Shrine based on the Mausoleum of Halicarnassos and the Forecourt based on the Acropolis in Athens. Milston’s design features flagpoles to represent the armed forces, an eternal flame and a cenotaph with sculpture created by George Allen. Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II dedicated the Forecourt during her first visit to Australia.

The WWI Shrine and WWII Forecourt form the structure of Victoria’s war memorial, with other conflicts remembered by statuary and garden elements, some of which have been relocated to the site.

The National War Memorial of Victoria

Part of proposal submitted by EE Milston

Ink and pencil on tracing paper

EE Milston 1976.0025

Panorama of city skyline, showing the forecourt during construction, undated

Composite photograph

Photographer unknown

EE Milston 1976.0025

View of the Forecourt and Shrine, undated

Print of pencil sketch, with watercolour and white poster paint

EE Milston 1976.0025

Cenotaph and Eternal Flame, undated

Ink on paper

Artist unknown

EE Milston 1976.0025

Queen Elizabeth II arriving at the Shrine, for ceremony of dedication, 28 February, 1954

Photographer unknown

OSBB 24

EE Milston 1976.0025

Pass to Official Enclosure, Shrine Forecourt, 28 February, 1954

Printed paper, with ink annotation

EE Milston 1976.0025

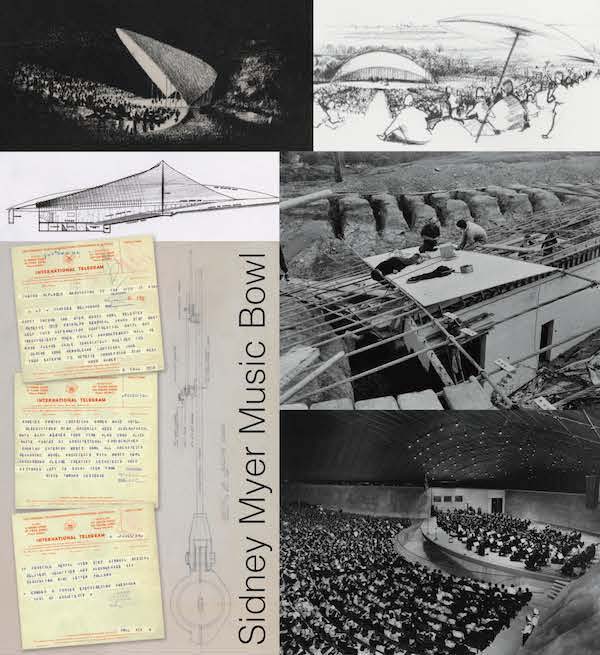

The Sidney Myer Music Bowl

The Sidney Myer Music Bowl project came about through the auspices of the Sidney Myer Charity Trust, bringing to fruition an idea expressed by businessman Sidney Myer.

Winner of the R.S. Reynolds award for architecture in 1959, ‘The Bowl’ was recognised as ‘a project needed by every community or city of any size in the world; a building used by people, semi-enclosing space for a cultural purpose’1

According to the jury for the Reynolds prize -

‘We are coming into an era where larger and light-weight, space spanning structures will be needed. Many drawings or diagrams of what such shapes might be have been published, but few proposals have solved the most difficult problem – the skin itself ... Here we have an architecture that is a strong statement of the problem-solving approach, which results in a fresh, original solution. The winners of this competition have done a remarkable job in joining several sciences and arts all into one cohesive design concept. This comprehensive structure demonstrates their combination into one unity; architecture, structural and electrical engineering, acoustics and landscape design become one …If the approach and principles of the winners are followed, architecture may soar to new levels of freedom, utility and grace.’

The Bowl has fixed seating for 2,100 people, with a total capacity of about 25,000 in the grounds, however in the mid-1970s rock concerts drew huge crowds extending into Kings Domain. While most people were unable to see the stage, the Bowl’s unique design allowed the sound to carry far into the trees. Though not the first building utilizing tensile cables and thin shell roofing, the design and engineering methods used in the Bowl project also carried far, stimulating rapid development of this type of construction.

- Excerpts from Jury Report, R.S. Reynolds Prize, published in Architectural Record, June 1959, Yuncken Freeman Architects Pty Ltd and Predecessors, 1984.0047 Unit 4

Concept drawings, night and day performances, undated

Early scheme drawn by Paul Wallace of Grounds Romberg Boyd

Photographic reproductions of charcoal sketches

Yuncken Freeman Architects Pty Ltd and Predecessors, 1984.0047.00017

Longitudinal section showing cable construction, 1959

Included in submission to competition for the R.S. Reynolds Prize

Yuncken Freeman Architects Pty Ltd and Predecessors, 1984.0047

Detail of leading edge, undated

Pencil on tracing paper

Yuncken Freeman Architects Pty Ltd and Predecessors, 1984.0047

Telegram advising award of the R.S. Reynolds prize, 1959

Yuncken Freeman Architects Pty Ltd and Predecessors, 1984.0047 Unit 4

Laying the first sheet of roof, 11 December 1958

Wolfgang Sievers, photographer

Myer Emporium, 1979.0180

Reproduced by permission, National Library of Australia

An early performance, showing the underside of the roof

Laurie Richards, photographer

Yuncken Freeman Architects Pty Ltd and Predecessors, 1984.0047

See also:

Boyd’s contribution to the Sidney Myer Music Bowl, UMA Bulletin, December 2014

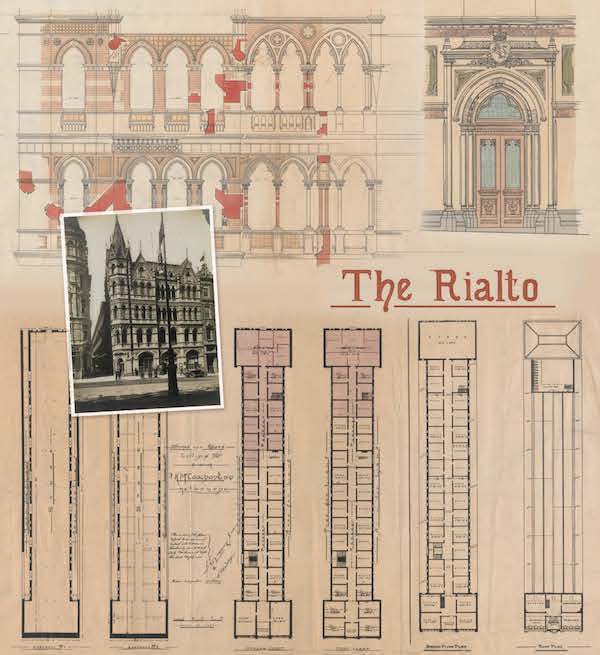

The Rialto

The Rialto building is now a luxury hotel, but it began as a warehouse and office building, with retail outlets at street level.

The Collins Street façade is designed in the distinctive version of the Venetian Gothic palazzo style favoured by boom period Melbournians, and features cement details, ceramic tiles and pressed zinc. Commissioned by businessman Patrick McCaughan in the late 1880s, architect William Pitt utilised the latest in fireproofing for the internal structure, incorporating fireproof floors, stone stair cases, isolated hydraulic lifts, metal strips instead of timber laths to support plaster and full height masonry internal walls.

A growing awareness of the need to preserve all aspects of Melbourne’s heritage in the 1980s saw preservation of 5 levels of urinals at the rear of the Rialto building, and conservation of many other details from past times. The Rialto is just one of a complex of interconnected 19th century commercial buildings through to Flinders Lane, and the relationship between the buildings has been maintained in the current use - the long east facade of the Rialto faces into a void under a glass atrium roof and opposite the former Wool Exchange building (1891) which is finished in a sympathetic style. The floor of the atrium is formed by the original bluestone cobbled laneway, which served the carts and wagons delivering products to the adjacent warehouses.

Early tenants of the Rialto building included the Melbourne Metropolitan Board of Works, responsible for providing Melbourne with a water and sewerage system and the law firm of Theodore Fink, younger brother of notorious lank speculator, Benjamin Fink. In addition to building plans by William Pitt, The University of Melbourne Archives holds records relating to both Fink brothers and records of one of the Rialto’s later tenants, the Melbourne Woolbrokers’ Association.

Construction of the Rialto Towers behind the original Rialto began in 1982, on the site of Robb’s Buildings. Melbourne's first skyscraper public observation deck operated in the Rialto Towers between 1994 and 2009 and the building hosted Melbourne's first Tower running event in 1989.

Details from plans for the Rialto Building, 1890

Architect, William Pitt

Ink and watercolour on paper

William Pitt 1977.0115

The Rialto Building, undated

Photographer unknown

OSBA 780

William Pitt 1977.0115

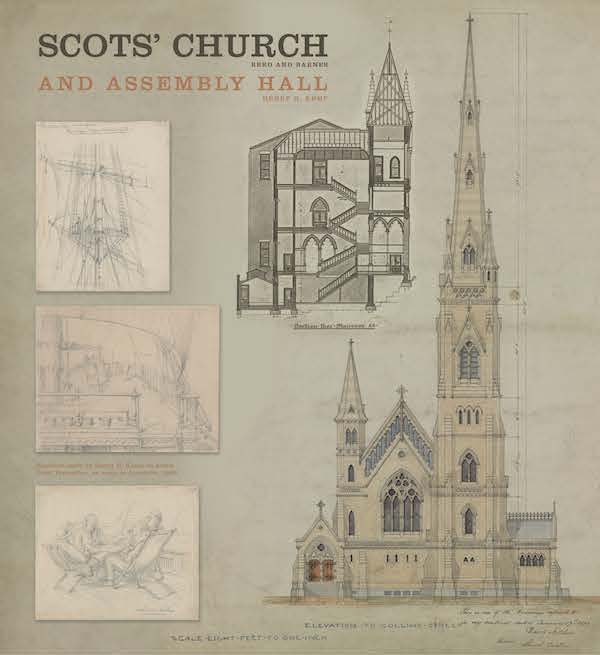

Scots' Church and Assembly Hall

Presbyterian services were held regularly in Melbourne from 1837, at the west end of Collins Street in a building shared with other denominations. The current Gothic Revival church on the corner of Collins and Russell streets was designed in 1871 by Joseph Reed of the firm Reed and Barnes, and built by David Mitchell, father of Dame Nellie Melba. It replaced a school which from 1841 was also used for church services on this site. A severe storm saw the height of the church spire reduced in the 1960s but it has subsequently been rebuilt to Reed’s original design. The Assembly Building was constructed just before WWI, also in the Gothic Revival style to complement the neighbouring church. It is on the site of an earlier Manse and was originally three stories high, with a fourth story added in 1935.

The two architects of the Scots Church complex were equally comfortable with works on paper as they were with brick and stone as seen in the items featured on the panel.

Joseph Reed enlivened his building plans with watercolour, representing not only the colour of building materials but also the effect of light and shadow on building elements. Reed and Barnes designed many other well-known Melbourne buildings including Wilson Hall, Melbourne Town Hall, The State Library of Victoria, Rippon Lea and the International Exhibition Building (now known as the Royal Exhibition Building). The Royal Exhibition Building has been inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List of cultural sites.

From an early age, Henry H. Kemp had intended to be an artist, and undertook sketching tours alongside his architectural studies. En route to Australia in 1886, he rendered scenes on board ship in delicate pencil, plotted his journey on a chart and kept a diary. On arrival in Melbourne, Kemp joined the practice of Terry and Oakden, later Oakden, Addison & Kemp, and worked on several major projects including Queen’s College at the University of Melbourne. He is best known for his later domestic designs in the Federation style with partner Beverley Ussher. After Ussher’s death in 1908, Kemp worked alone until forming a partnership with George Inskip from 1911-1913. After WWI, Kemp worked in partnership with his nephew, F. Bruce Kemp.

Assembly Hall, section through central staircase, 1913

Architect, Henry H Kemp

Copy printed on tracing paper

Bates Smart McCutcheon 1983.0125 (Job 23)

Sketches made on board Loch Vennachar, 1886

Henry H. Kemp

Pencil on paper

Henry H. Kemp 1976.0024

Scots’ Church elevation to Collins Street, 1871, drawing Number 10

Architect, Joseph Reed

Watercolour & ink on paper

Contract document, signed by David Mitchell, 1873

Bates Smart McCutcheon 1983.0125 (Job 23)

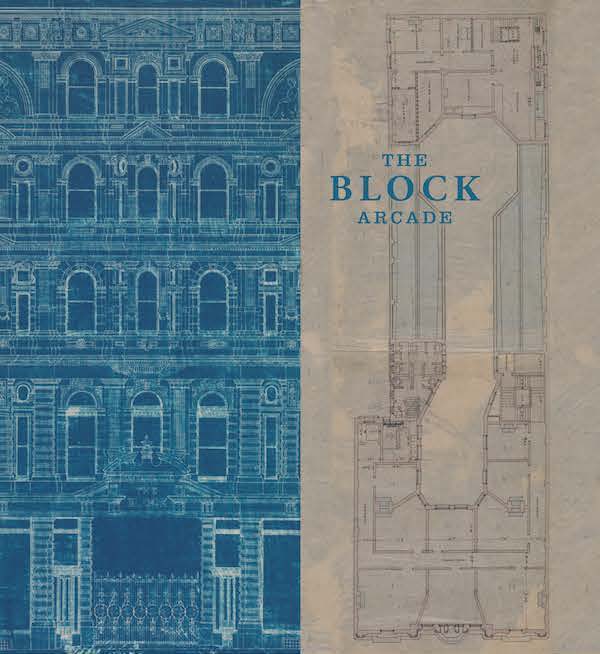

The Block Arcade

The arcade’s name refers to the fashionable late 19th century habit of perambulating ‘the block’ formed by Collins, Elizabeth, Swanston and Little Collins Streets. The site of the Collins Street wing of the Block Arcade, ‘Melbourne’s grandest and most fashionable shopping arcade’ was originally the site of something more humble, Briscoe’s Bulk Grain Store. When Briscoe’s moved in 1883, the George brothers opened a drapery store that was destroyed by fire in 1889. The business relocated further east on Collins Street where it became known simply as ‘Georges’.

Shortly after the fire, David C Askew of the firm Twentyman and Askew was commissioned by the City Property Company Pty Ltd to design an L shaped shopping arcade connecting Collins Street and Elizabeth Street. The featured plan clearly shows the kink in the building that is due to the underlying configuration of land subdivisions.

In 1892 the city of Melbourne was flourishing, and city buildings mirrored the style of those in Europe. The design for The Block is similar to the Galleria Vittorio in Milan, where shoppers had leisure to browse protected from weather and the dust of the streets. The high-quality finishes and attention to detail of the facades and the shopping arcade were carried through to the office levels above. At the time of its opening, the arcade boasted 15 milliners, three lace shops and a photographic studio as well as the first Kodak shop in Melbourne, and the Hopetoun Tea Rooms which is still trading today.

The minutes of the City Property Company, 27 January 1892, record that the directors discussed ‘the desirability of making an effort to secure the completion of “The Block” and to arrange the finances of the company upon a satisfactory basis’. By 1923 the company was in liquidation. The cost of maintenance and incorporation of current safety features is a constant challenge to owners of properties like The Block. Many other arcades established in the late 19th century have not survived or have been altered considerably. In contrast, the Block Arcade has retained most of its original features and has been extensively refurbished so that it maintains its reputation as one of the places where it is fashionable to be seen and to shop.

The Block Arcade, 1892

Blueprint, Collins Street Elevation

Print made by Peterson & Co, 421 Collins Street

Bates Smart McCutcheon, 1968.0013 (Job 174)

The Block Arcade, 1892

Fourth Floor Plan, Collins Street wing

Architect, David C. Askew

Ink & watercolour on glazed linen, pencil annotations

Bates Smart McCutcheon, 1968.0013 (Job 174)

Minutes of Ordinary Meeting of Directors, 27 January 1892

City Property Company Pty Ltd 1974.0025

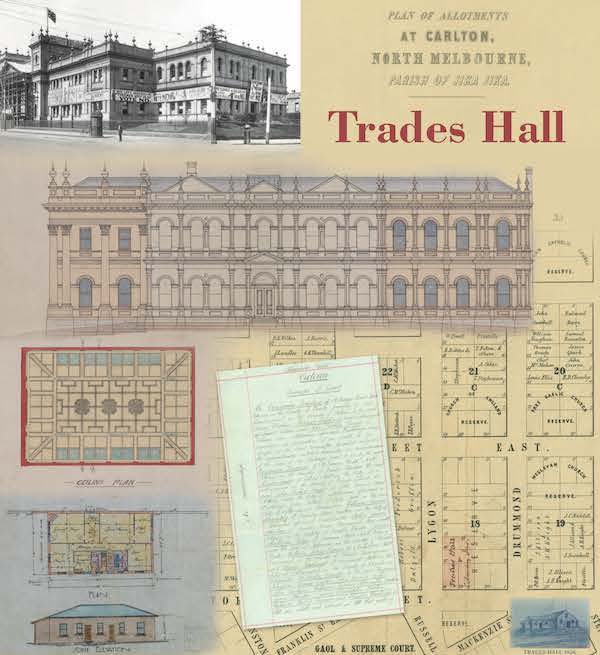

Trades Hall

Many campaigns have gone out from Trades Hall - by radio during the depression, by banners on the façade, by protests and marches. An embodiment of the slogan ‘Proud to be Union!’ Trades Hall has provided a physical home for many unions and allied groups since the middle of the 19th century.

The first hall was a simple structure built to commemorate the successful 1856 campaign for an 8 hour day and to provide a meeting place where members could pursue educational and cultural aims, and plan further industrial strategies. This building stood until about 1917. By the 1870s, plans for a more substantial Trades Hall and Literary Institute were taking shape, with Joseph Reed as architect. Many phases of extensions and alteration have taken place since then, including many undertaken by the architectural practice established by Reed and Barnes that continues to this day. As unions grew in strength during the 1880s, the Trades Hall also grew. Following a successful strike by the newly formed Tailoresses’ Association in 1883, a Female Operatives Hall was built, as at that time women were not permitted in the committee rooms. This building was demolished in 1960.

Trades Hall became increasingly grand, but its caretaker lived on site in a simple cottage, more like the housing of most union members. Despite his presence, in 1915 Trades Hall was robbed by notorious criminal Squizzy Taylor. While the Union movement has seen many changes over the years, Trades Hall endures – the oldest continually used trade union building in Australia.

In commemoration of the Anti-Conscription Campaign, December 1917

Photographer unknown

UMA/I/2656

Victorian Trades Hall Council 1988.0062

Proposed Additions to Trades Hall, 1882

Elevation to Victoria St, drawing No 5

Contract document

Ink and watercolour on paper

Bates Smart McCutcheon 1968.0013 (Job 20)

Detail of Ceiling Plan, 1890

Trades Hall Council, Additions to Council Chamber &c, drawing No. 2

Contract document

Ink and watercolour on paper

Reed, Smart & Tappin, architects and surveyors

Bates Smart McCutcheon 1968.0013 (Job 20)

Amended Plan Caretaker’s Quarters, undated

Ink and watercolour on glazed linen

Bates & Smart, architects

Item 29/13

Victorian Trades Hall Council 1988.0062

Document concerning the transfer of land to the Trades Hall and Literary Institute

Unsigned copy, dated 1885

Victorian Trades Hall Council 1988.0062

Plan of allotments at Carlton, North Melbourne, showing the land to be transferred shaded red

Plan prepared by Surveyor General’s Office, June 18, 1856

Victorian Trades Hall Council 1988.0062

The First Trades Hall, 1856

Detail from the mount of a photograph of the Eight Hour Day Jubilee Committee, 1906

Victorian Trades Hall Council 1988.0062

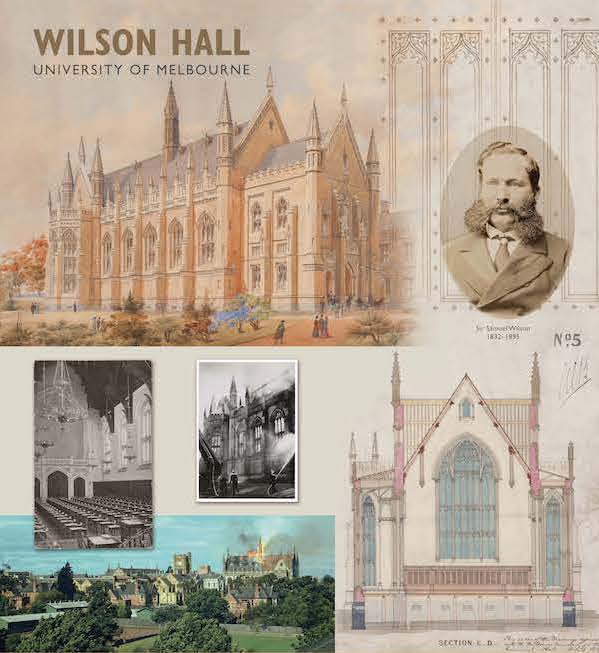

Wilson Hall

Wilson Hall has been an integral part of the University of Melbourne landscape since the first building to bear this name was completed in 1882. Built as a venue for examinations and conferring of degrees, the Hall has been at the very centre of the university experience for generations of students. As the gathering place for grand celebrations and solemn occasions, the Hall has come to symbolise in bricks and mortar the unity and shared goals of the wider University community.

Made possible through a generous donation by wealthy pastoralist Sir Samuel Wilson, the original Wilson Hall was designed in the perpendicular gothic revival style by architectural firm Reed & Barnes. For 70 years it dominated the centre of the University, soaring in height above the surrounding buildings. From all approaches its turrets and mass clearly located the University within the surrounding landscape and became an instantly recognisable landmark.

On 25 January 1952 fire destroyed the roof and badly damaged the west wall of the Hall. This calamity was keenly felt by the University community which, over the following year, was polarised by a debate over whether to restore the gothic ruins or rebuild in modern style. Eventually succumbing to financial realities, the gothic splendour of the original Hall gave way to the modern 1950s building that we know today. Designed by the architectural firm Bates, Smart & McCutcheon (formerly Reed & Barnes) the building was completed in 1956. Today the new Wilson Hall, with its highly crafted interior and integral artworks, carries on the tradition of the original Hall as the ceremonial centre of the University.

Exterior presentation view of Wilson Hall c 1877

Reed & Barnes [attributed to AC Smart]

Watercolour on paper

Bates Smart McCutcheon Collection, 1968.0013 (Job 31)

Sir Samuel Wilson c 1879

Albumen silver print published in

Proceedings on laying the memorial stone for the Wilson Hall of the University of Melbourne

Stillwell & Co, Melbourne, 1879

Detail of design for doors

Drawing no 22, 1877

Ink, watercolour on paper

Bates Smart McCutcheon Collection, 1968.0013 (Job 31)

Wilson Hall south interior elevation section C-D

Drawing no 5, 1877

Ink, watercolour on paper

Bates Smart McCutcheon Collection, 1968.0013 (Job 31)

Wilson Hall fire, 25 January 1952

Photographed by J. Douglas Hicks from the roof of the Walter & Eliza Hall Institute

35mm kodachrome colour transparency

University Photographs, 1993.0058.00002

Firemen battling the fire at Wilson Hall, 25 January 1952

Herald Sun newspaper, photographer unknown

Gelatin silver photograph

University Photographs, 2017.0071.00464

Wilson Hall set up for examinations, c 1910

Photolithograph postcard

University Photographs, 2017.0071.00865