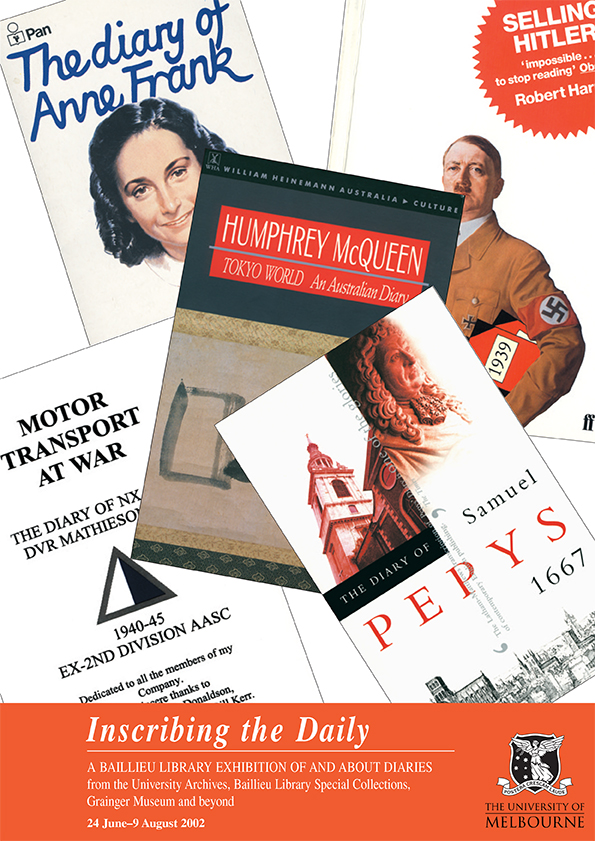

Inscribing the daily: An exhibition of and about diaries

Inscribing the daily: An exhibition of and about diaries

Exhibition

24th Jun 2002 - 9th Aug 2002 at Baillieu Library, The University of Melbourne

This exhibition, ‘Inscribing the Daily’, aims to introduce a selection of diaries and related material from the University’s library, archives and Grainger Museum collections. This exhibition, ‘Inscribing the Daily’, aims to introduce a selection of diaries and related material from the University’s library, archives and Grainger Museum collections.

Introduction

There were moments in preparing this exhibition when 2002 seemed ‘the year of the diary’.

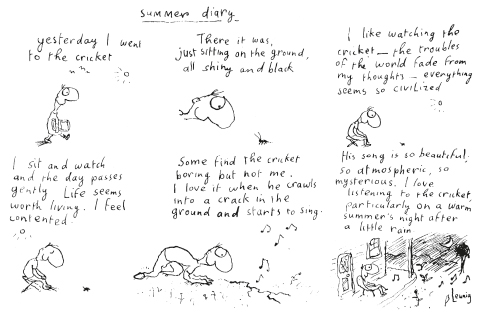

January opened with The Age carrying Michael Leunig’s car- toon series ‘Summer Diary’, while The Australian launched a year-long series of wartime diary extracts tracking the events of 1942. Elsewhere in the press, the diary as a device around which to structure a story was as popular as ever, be it asylum seekers, nurses or celebrities. The year’s first issue of Meanjin carried Helen Garner’s admission about her 1977 novel Monkey Grip: ‘I might as well come clean. I did publish my diary’. Publishers’ enthusiasm for diaries remained strong, both as authentic historical documents and works of fiction. Melbourne University Press released Professor Ron Ridley’s edition of the diary of one of our former Vice-Chancellors, Raymond Priestley, and the children’s publisher Scholastic released the first of its ‘My Story’ series of fictional historical diaries, Anita Heiss’s Who am I? The Diary of Mary Talence, Sydney 1937.

The phenomenon was hardly restricted to publishing, however. In April the local cinema screened Paul Cox’s latest film, The Diaries of Vaslav Nijinsky and in the same month came news of a BBC crew working on converting The Diary of a Welsh Swagman into a documentary.

This is fortuitous background. The curator’s interest in diary originated in work on the C. E.W. Bean papers and diaries at the Australian War Memorial. Stimulated since by the occa- sional reference in the professional archival literature, it was rekindled via a University of Melbourne Archives project coordinated by Fay Anderson in 2001. This was a ‘History in the Field’ project undertaken by two third year history students, Kate Leihy and Agata Kula, to list and assess a selection from the hundreds of diaries in the University Archives.

This exhibition, ‘Inscribing the Daily’, aims to introduce a selection of diaries and related material from the University’s library, archives and Grainger Museum collections, while also acknowledging the wealth of other collections. Through this selection, we plan to highlight the diary as a social and publish- ing phenomenon, an important resource for historical research and literary inspiration, and a legitimate object for study in its own right.

Woven through the exhibition’s dozen or so mini themes is the enduring question of motives and audiences. It is rare for diarists to explain — to themselves, to us — what motivates them to write. But whatever triggers them, it can become a duty. It can also be, to use Katie Holmes’ phrase, ‘an itch to record’, and as she reveals about certain Australian women in the 1920s and 1930s, much more as well. Indeed she and others systematically analysing the phenomenon have had little diffi- culty in establishing clear patterns of motivation. Thomas Mallon provides one of the best known explanations, identify- ing seven types of diary writers: chroniclers, travellers, pil- grims, creators, apologists, confessors and prisoners.1 Most scholars have been more specialised, looking at a specific gen- der and time span, such as women diarists as noted above, or soldiers or 19th century travellers to Australia.2 Others have ocussed on one set of motivations, for example linking diary writing to strong psychological motivations and a sense of identity, such as archivist Sue McKemmish’s notion of ‘evi- dence of me’ and Anthony Giddens’ ‘narrative of the self’. Interestingly, in the past 20 years, the diary as journal of inner feelings and self-identity has also become popular with spiritual advisers and grief and trauma counsellors.

One should not overlook more practical explanations of course. The diary as ‘log book’ has a myriad contemporary and histori- cal illustrations, reflecting established scientific, professional, law enforcement, and military requirements or practice. And whether on land, ice or sea, the explorer was also recorder of diary and journal, a chart maker and scientific observer and forthcoming author. The diary which doubled as a note book, sketch book or ‘commonplace book’ also had fairly immediate uses for writers, painters and autobiographers. The diaries of the renowned war correspondent and war historian of Australia in the First World War, Dr C. E. W. Bean certainly were written for immediate self-reference.3 Timothy Garton Ash illustrates another variation of the diary being used for the author’s own reference, enabling him to cross check his own account of life in East Germany with the voluminous dossier kept on him during the same period by the Stasi.4

Whatever the reasons motivating diarists to daily toil, usually the result is intended at least in the short term exclusively for the author’s reference. Hence the care taken with storage away from prying eyes, with the writing (at times with symbols or abbreviations) and with the diary’s ultimate fate via instruc- tions to one’s executors. With libraries and archives, this pattern is reversed. A single motive drives them — to collect and preserve historical evidences, with minimal or better still no access conditions, for the use of historians, biographers, journalists and others researching the past.

These are generalisations of course. In fact those who have examined diaries systematically have concluded that subcon- sciously all diarists are writing for an audience, if not immedi- ately, then for an eventual posterity. ‘Ever within the breasts of all diarists’, wrote A. A. Milne, there is ‘the hope that their diaries may some day be revealed to the world’.5 Here the core motive for writing the diary can identify the intended audience, with soldiers, sports stars, travellers and politicians well repre- sented among those happy to share quite early their daily observations and thoughts.

Now, with personal websites able to broadcast the images and sounds and words of one’s diary instantaneously, we have the ultimate deliberate and unselfconscious diarist, producing real time continuous reportage of the life as lived. The phenomenon started by Jennifer Ringley of Jennicam fame recalls the words of Christopher Isherwood’s 1930s Berlin diary, ‘I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking’.6

The subject of diaries is vast, as is the scholarship about (and based on) them. We claim no expertise, just a place in the front stalls.

References

- See A Book of one’s Own: people and their diaries (Ticknor and Fields, 1984). Anthologists too have their categories, though usually stressing diversity. See for instance Alan and Irene Taylor, editors, The Assassin’s Cloak: an anthology of the world’s greatest diarists (Canongate Books, 2000).

- Such categories represent the interests of the key Australian schol- ars; see, for example Katie Holmes, Spaces in her day: Australian Women’s Diaries of the 1920s and 1930s (Allen and Unwin, 1995), Andrew Hassam, Sailing to Australia: shipboard diaries by nineteenth-century British emigrants (MUP, 1995), and Bill Gammage, The Broken Years: Australian Soldiers in the Great War (Penguin, 1975). It need hardly be said that editing a single diary for publication can also require deep scholarship.

- See Gallipoli Correspondent; the frontline diary of C. E. W. Bean selected and annotated by Kevin Fewster (George Allen and Unwin, 1983).

- Ash describes the results of this cross matching in The File (HarperCollins, 1997).

- A. A. Milne, ‘The diary habit’, in Not That it Matters (tenth edition, Methuen, 1933), p. 105.

- Christopher Isherwood, ‘A Berlin Diary August 1930’, in Goodbye to Berlin (Penguin, 1945), p. 7.

Chris Wallace-Crabbe

Most diaries contain more than writing. An intimate journal might also have a loved one’s hair, ribbon or other keepsake. The more pedestrian might have business cards, ‘to do’ lists and newspaper clippings. In the case of creative writers, their diaries can become repositories of observations, one liners, thoughts, early drafts of poems, and even visual prompts which operate as an eclectic resource of ideas for future poetry and plots. They are part diary, part aide-memoir, part scrapbook, and part commonplace book.

Nothing better illustrates this than the diaries of Professor Emeritus Chris Wallace-Crabbe, a former Director of and now Professorial Fellow at the Australian Centre, University of Melbourne. A poet, anthologist, editor and literary critic, his extensive literary archive includes dozens of diaries kept over the past 40 years.

Item 1

Journal 1965 — to America, Travel diary/notebook, 1965–1966, opened at 28 Feb 1966 where he describes an evening at Yale University in honour of the poet, essayist and critic Randall Jarrell who died the previous year. The entry (and the following pages) reports his talk with Robert Lowell and the latter’s view of Australians R. D. FitzGerald, Sidney Nolan and Alec Hope.

Item 2

The New York Notebook Thanksgiving, 1987 and Boston/Cambridge to April 1988, opened at entries for late February 1987 covering typical detail about lunches and direct quotes (Morag Fraser and Frank Jackson), current reading, and newspaper ‘crazy headlines’ (‘SNEEZING CAN INCREASE THE SIZE OF YOUR BUST...’).

Item 3

Journal — B January 1972 — opened at undated entry headed ‘[For my novel]’ and describing plot outline triggered by receipt of ‘Campy postcard’. Glued on page opposite is postcard of nativity scene.

Item 4

Diary/notebook 1974–1975, opened at page with newspaper cutting and entries for October 1974 beginning ‘Melbourne or the Bush has been published at last: a great relief after all my anxiety over the wavering fortunes of A&R under the sin- ister guidance of Gordon Barton. It looks a very slim little book, but it reads quite well, and good prose is, after all, the main thing. That, and some spark of imagination’.

Item 5

May–September 1973, Diary/notebook, opened at page of miscellaneous notes, including ideas for poems about Gallipoli, a list of current reading, and quotations including transcription of extract from Virginia Woolf’s Growing observing that, ‘Diaries and letters almost give an exagger- ated, one-side picture of the writer’s state of mind’.

Item 6

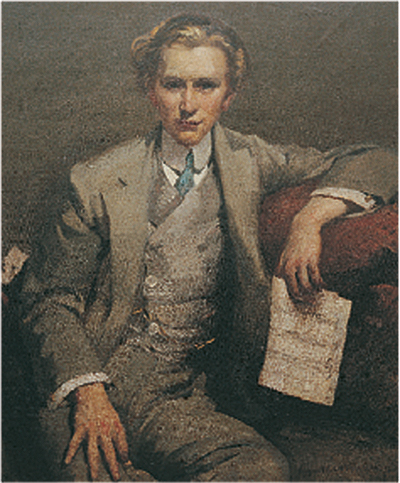

Meanjin Quarterly 2/1970, opened at a Louis Kahan portrait of Wallace-Crabbe and the beginning of Peter Steele’s commentary on his poetry ‘To move in Light’.

Sir Robert Menzies

Sir Robert Menzies (1894–1978) was Australia’s longest serving Prime Minister, as well as being a distinguished and well known graduate of the University, and serving as its Chancellor between 1967 and 1972. He is represented in the Baillieu Library Special Collections, primarily through his extensive personal library of over 4000 volumes. For purposes of this exhibition, he represents a mid-point between those politicians who were diligent diarists (eg Clyde Cameron, Peter Howson and Neil Blewett), and those who shunned the very idea.1 In a famous passage of his memoirs, quoted in full in the exhibition, Menzies reflected on his limited diary writing and their value. He began by noting ‘Except on two journeys abroad, I have never kept a diary...’ and ended ‘My executors will do me a good service if they use the incinerator freely’.2

Item 7

Dark and Hurrying Days: Menzies’ 1941 Diary edited by A. W. Martin and Patsy Hardy (National Library of Australia, 1993).

Item 8

Commemorative plaster bust of Menzies, based on a cartoon by Les Tanner and sold by the Bulletin, Jan–Feb 1966. Item 9 Selection of published diaries from Menzies’ personal library.

References

- See Clyde Cameron, The Cameron Diaries (Allen and Unwin Australia, 1990); Peter Howson, The Howson Diaries: the life of politics (Viking, 1984); and Neil Blewett, A Cabinet Diary (Wakefield Press,1999). One of the best loved politician’s diaries is technically fiction, i.e. Jonathan Lynn and Antony Jay, editors, The Complete Yes Minister: the diaries of a cabinet minister by the Right Hon. James Hacker MP (BBC Books, 1988).

- Sir Robert Menzies, Afternoon Light: some memories of men and events (Cassell, 1967, pp. 44–45).

Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys was born in London on 23 February 1633. Bright and capable, he performed well at school, which led to a scholarship at Magdalene College, Cambridge. Pepys held an important post in the British Navy where he distinguished himself as a hard worker and reformer. Admired and respected by his contemporaries, he also served as the president of the Royal Society from 1684 to 1686, and twice as a member of parliament.

Pepys has become most famously known for his diary, begun at the age of 27 and maintained for almost ten years when failing eyesight forced a halt. Learned and accomplished, his many areas of interest included politics, the arts, science, morals, food, fashion and books. Pepys wrote on the eve of the Restoration, and many important political and social events are recorded in the diary such as the plague and the Great Fire of London.

The diary and Pepys’ extensive book collection were bequeathed to his old college, where the diary was not rediscovered for over 100 years, and for a time, unreadable — he had written a form of shorthand, freely and unselfconsciously, only for himself. The diary was first published, heavily edited, in 1825, was immediately popular and has been reprinted in many different editions since. Each edition has been gradually expanded, culminating in Latham and Matthews’ definitive edition first published from 1970 to 1983 (reprinted several times in the 1990s and in 2000), the first one to give a full and unedited transcription.

Item 10

Memoirs of Samuel Pepys, Esq., F.R.S., Secretary to the Admiralty in the reigns of Charles II. and James II / comprising his diary from 1659 to 1669, deciphered by the Rev. John Smith, A.B. of St. John’s College, Cambridge, from the original short-hand MS. in the Pepysian library, and a selection from his private correspondence, edited by Richard, Lord Braybrooke (Henry Colburn, 1825). The first edition, volume 1, opened to show the engraved frontispiece portrait of Pepys.

Item 11

Memoirs of Samuel Pepys, Esq., F.R.S., Secretary to the Admiralty in the reigns of Charles II. and James II., comprising his diary from 1659 to 1669, deciphered by the Rev. John Smith, A.B., from the original short-hand ms. in the correspondence, edited by Richard, Lord Braybrooke, 2nd edition, in five volumes (Henry Colburn, 1828).

Item 12

The Diary of Samuel Pepys edited by Robert Latham and William Matthews, nine volumes (University of California Press, 2000).

Item 13

Kay Craddock, Antiquarian Bookseller, Catalogue No. 171, announcing the sale of Stuart Sayers’ Pepys collection, opened to indicate the monetary value in 1995 of early editions of the published diary.

Item 14

Reproduction of Pepys’ handwriting, showing his usual handwriting and the shorthand which he used. From the 3rd edition of Lord Braybrooke’s version of the diary (H. Colburn, 1848–1849)

Dr Orde Poynton

Dr Orde Poynton (1906–2001) is known at the University of Melbourne as one of the Baillieu Library’s most generous donors. Though he is best remembered now through the collec- tions of prints, rare books and paintings, the Poynton collec- tions includes one small reminder of earlier years. He was a pathologist at the Institute for Medical Research, Kuala Lumpur and with the British Army at the fall of Singapore. There followed three and a half years as a POW. He arrived in Perth courtesy of the Red Cross in poor health from years of incarceration, with a tiny pocket diary.

Item 15

Head and shoulders portrait of Poynton by Ivor Hele, c 1950.

Item 16

Collins Century Diary for 1942 kept by Poynton in Changi prisoner of war camp, 1942–1943, containing brief but very frank comments about the behaviour of the Allies as well as his captors. It is opened at entries for late February–early March 1942.

Writers' Diaries and Writer's Novels

The literary device of the fictionalised diary stretches back at least to George and Weedon Grossmith’s 1892 work The Diary of a Nobody. Sue Townsend’s Adrian Mole is perhaps better known. Equally established is the diary doubling as the novelist’s first draft, Anaïs Nin being an obvious example.

Locally there is Helen Garner. Twenty five years after writing her now classic novel Monkey Grip, which some critics alleged was just a fictionalised version of her diary, she acknowledged that indeed it was very largely based on her own diaries. The quotation, from a recent issue of Meanjin, is reproduced in full in the exhibition.9 Intriguingly, the dust jacket described her as a ‘compulsive scribbler, journal-keeper and letter- and note- writer’. Those familiar with Barry Oakley’s published diary selections Minitudes (Text Publishing, 2000) may wonder if a similar admission will result from his new novel Don’t Leave Me (Text Publishing, 2002).

Item 17

Monkey Grip by Helen Garner (McPhee Gribble, 1977).

Item 18

Helen Garner, close-up photo reproduction from back cover of Meanjin no 1, 2002, pp. 40-41, which included her article, ‘I’, where Garner explains the diary connection.

Varieties of Diaries

At its core, a diary encompasses information about events, observations, thoughts and actions recorded chronologically. The most diligent diarists do achieve a quotidian output,10 but more often there will be gaps and catch-up entries where several are written up retrospectively. A record created chrono- logically of course covers many kinds of record making, stretching back to the development of writing when climatic, astronomical and other cyclical phenomena were observed and recorded. The two principal types are those kept for purely personal reasons (eg. the intimate journal of thoughts and feel- ings or the travel diary) and those maintained for official busi- ness reasons (eg. an appointments diary or a log book). Within the second category particularly, there exist innumerable technical variants.

Item 19

Engineer Log of Great Britain SS Commencing Aug 21st 1852 First Voy. To Australia, the composite log/journal kept by the 19-year-old Reginald Bright (1833–1920), opened at the entry for Thursday 30 September (1852) and recording, on the left, technical data about the operation of the ship which employed steam, and on the right, consumption of stores, fuel and general remarks.

Item 20

Bound private ledger July 1876–June 1885 maintained by Felton Grimwade and Co., opened to show periodic payments for insurance and rent, 1876–1877.

Item 21

James Graham Melbourne Port Phillip Cash Book Commencing 6 April 1839, opened to show cash payments received from the Bank of Australasia for July 1840.

Item 22

Prescription book kept by Charles Ogg, a prominent Collins Street chemist, opened to show entries from Sunday 14 March to Tuesday 16 March 1926. Item 23 Accounting Journal, 1856–1862, maintained by the biscuit manufacturer T. B. Guest, displayed closed to reveal the reinforced leather binding. tem 24 Business/personal diaries, 1952, 1953 and 1955 maintained by Howard Dicker (1903–1981), a small sheep and cattle farmer based at Stewarton, north central Victoria. Item 25 A selection of printed diaries — part stationery, part advertis- ing, part fashion statement — drawn from the University Archives’ holdings, private collections of staff, and in case of the pre-teen lockable intimate diaries, a supermarket!

Melbourne University Press

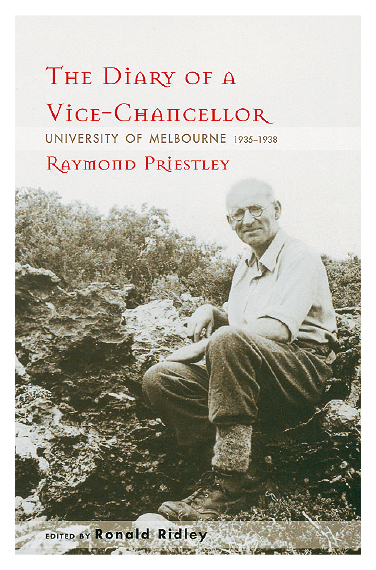

Diaries and journals are rarely best sellers. However, the production of beautifully designed limited print runs of scholarly editions has long attracted university presses such as Melbourne University Press. Particularly through the Miegunyah Fund, established by bequests under the wills of Sir Russell and Lady Grimwade, Melbourne University Press has found the means to share with a wider readership original diaries and journals of early Australian exploration, settlement and governance. Undoubtedly the pride of its list is Ray Parkin’s prize winning H. M. Bark Endeavour: her place in Australian History — perhaps fitting given Sir Russell’s interest in Captain James Cook. This, and its most recent diary publication, Professor Ron Ridley’s The Diary of a Vice- Chancellor: University of Melbourne 1935–1938; Raymond Priestley, are featured elsewhere in the exhibition.

Item 26

A selection of Melbourne University Press’s diary and journal publications.

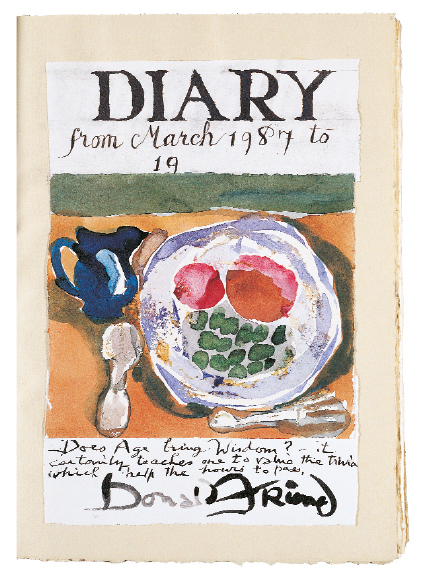

Donald Friend

Donald Friend (1915–1989), the second son of a New South Wales pastoralist, was one of Australia’s leading 20th century artists and writers. His varied life included time in Nigeria, England, a period of service during World War Two in the Australian Army, Sri Lanka and Bali. He knew many other renowned Australian painters, Sir Russell Drysdale being one of his closest friends.

Although he wrote 12 books, as a writer Friend is best known for his diaries, as are artists John Olsen and Judy Cassab.1 Begun when he was aged 14, they comprise 49 volumes, most including delightful and occasionally ironic and erotic illustrations. Selections of both diary content and drawings have been published, the most ambitious being initiated in the past two years by the National Library of Australia, which holds all but five of the diaries.

Item 27

Gunner’s Diary: written and illustrated by Donald Friend (Ure Smith Pty Limited, 1943).

Item 28

The Diaries of Donald Friend. Volume 1, edited by Anne Gray (National Library of Australia, 2001).

Item 29

The Genius of Donald Friend: drawings from the diaries 1942–1989, selected and introduced by Lou Klepac (National Library of Australia, 2000).

Display case lining

Poster and flyers from the National Library of Australia, from the Gray and Klepac editions.

References

- John Olsen, Drawn From Life (Duffy and Snellgrove, 1997) and Judy Cassab, Judy Cassab Diaries (Alfred Knopf, 1995).

Forgeries

To the popular imagination, documents convey an inbuilt credibility. Their ‘primary’ status derived from creation ‘inside’ the action gives them authenticity and reliability. External features such as the handwriting, signatures and the markings of the bureaucracy machine at work all vouch for their trustworthiness.

Not surprisingly, this standing as a reliable witness automatically accorded to records has attracted the forger. Criteria and techniques for analysing documents were codified by Dom Jean Mabillon in his De Re Diplomatica (1681) and established the classic internal and external characteristics of a document that confirm it is what it purports to be. This technique known as diplomatics, subsequently supported by advances in analysing handwriting, paper and ink have been needed to this day. Already this year we have seen a forged document used by Senator Heffernan to support allegations against Justice Michael Kirby. The issue of questionable passports and identity papers has also been a factor in many recent stories about welfare fraud and terrorism.

Diaries too have tempted the forger. One of the 20th century’s most contentious and politically charged instances involved Sir Roger Casement, who was executed for treason in 1916 for attempting to recruit aid in Germany for the cause of Irish independence. According to his supporters, diaries detailing his promiscuous homosexual activities were fabricated and selectively leaked to undermine a growing campaign to stay his execution. The majority of expert opinion now supports the diaries’ authenticity.1

Internationally, the 20th century’s most notorious forger was a West German memorabilia dealer Konrad Kujau. In 1983 he briefly duped Der Stern and historians (most famously, Hugh Trevor-Roper) by producing 62 diaries ostensibly written by Adolph Hitler between 1932 and 1945. In Australia, doubt still surrounds the diary of Susan Kemp, the student at the centre of a sexual misconduct case involving Professor Sydney Orr at the University of Tasmania in the 1950s.2

There have been times, too, when the historian (such as Ronald Reagan’s biographer Edmund Morris) brazenly invents diary sources, and the hoaxer openly produces a spurious diary — or diary story!

Item 30

Selling Hitler by Robert Harris (Faber and Faber, 1986).

Item 31

Caleb Carr, ‘James the Ripper?: a document that claims to provide the solution to the greatest unsolved crime spree of all time’, a skeptical review of The Diary of Jack the Ripper edited by Shirley Harrison from The New York Times Book Review, 12 December 1993, p. 12.

Item 32

Glenn R. Owen, ‘Diary exposes vital evidence in Kelly trial’, The Age, 1 April 2000, p. 2. Item 33 Two issues of The Observer (June 1958) referring to the Orr case, that for 14 June opened at A. K. Stout’s article ‘The Orr Trials and Miss Kemp’s Diary’.

Item 34

My secrete log boke..., by Christopher Columbus purporting to be written by Columbus, (Duesseldorf, Felix Bagal, 1890). A spurious work created by the painter, draughtsman and caricaturist Karl Maria Seyppel (1847–1913), in antiquated English and made with paper and binding attempting to suggest an appearance damaged by seawater.

References

- See ‘Doubts dispelled over Casement diaries, 86 years on’, in The Age 14 March 2002; Colm Tóibín, ‘A whale of a time’, in London Review of Books, 2 October 1997, pp. 24-27.

- See W. H. C. Eddy, Orr (Jacaranda Publishers Pty Ltd, 1961), esp chapter 24; A.K.Stout, ‘The Orr trials and Miss Kemp’s diary’, in The Observer 14 June 1958, pp. 259–261; Cassandra Pybus, Gross Moral Turpitude: the Orr case reconsidered, William Heinemann Australia, 1993, pp. 118–119; and Peter McPhee, ‘Pansy’: a life of Roy Douglas Wright (Melbourne University Press, 1999), p. 121.

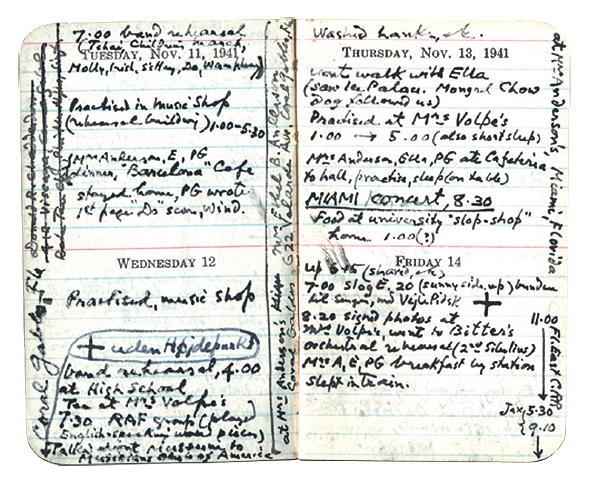

Percy Grainger

Percy Grainger (1882–1961) was born and spent his formative years in Melbourne, but attained celebrity status as a concert pianist in the US, Europe and the Commonwealth, and was equally renowned as a composer. His extraordinarily full life also included achievements as a pioneering ethnomusicologist, clothes designer, collector, artist and inventor of proto electronic music machines.

Grainger was a self-absorbed, meticulous documenter of his own life and circle. The two main legacies of that recording and collecting are the holdings of the Percy Grainger Library at White Plains, New York, and the Museum he established in the mid-1930s at the University of Melbourne. The latter includes almost all of his diaries and daybooks, which have proved invaluable to scholars in compiling a comprehensive picture of Grainger’s life, including his reading and travel.

Item 35

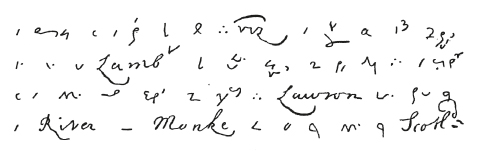

A selection of Grainger’s diaries and daybooks, including that for 1941 opened at 11–14 November to show his detailed recording, some in coded symbols and Danish.

Item 36

The 1928 journal of Antonia Sawyer Morse, Grainger’s manager, opened at her description of his wedding at the Hollywood Bowl, Los Angeles, on 9 August 1928.

Item 37

Tables from David Parr’s doctoral thesis, Percy Grainger as ‘Educator-at-Large’: the formation, expression and propaga- tion of his manliness (University of Queensland, 1998) summarising Grainger’s key literary influences (p. 32) and better known walking feats (p. 84). Both tables were compiled from a study of Grainger’s archives, including his diaries and daybooks.

Item 38

Colour reproduction of Rupert Bunny’s portrait of Grainger, ca. 1902–1904.

The Endeavour Holograph Journal of Captain James Cook

The voyages of discovery of Captain James Cook (1728–1779) generated varied documentation, and illustrate every possible aspect of the diary and its related forms canvassed in this exhibition. Thus we have a range of chronological records (personal and official journals, contemporary copies, official logbooks, civilians’ parallel journals, even visual records); the reverence shown to the iconic holograph journal; published versions that helped to create fame, wealth and controversy; and numerous amateur and scholarly efforts to untangle the truth. Thirty years ago M. K. Beddie’s Bibliography of Captain James Cook (Library of New South Wales, 1970), listed over 1100 items relating to the first voyage alone.

Item 39

Remarkable Occurrences: the National Library of Australia’s first 100 years 1901–2001, edited by Peter Cochrane (National Library of Australia, 2001), opened at an illustra- tion of Cook’s holograph journal and Professor Greg Dening’s reflections on the National Library’s number one treasure. The history’s short title is taken from the opening lines of the journal.

Item 40

The Journal of H.M.S. Endeavour 1768–1771 by Lieutenant James Cook (Genesis Publications Limited in association with Rigby Limited, 1977). Number 74 of 500 facsimile copies of the holograph journal, presented to the University of Melbourne Library by the Friends of the Baillieu Library. Opened at the entry for Thursday 19 April 1770, when the east coast of Australia was first sighted (mid-point of left page).

Item 41

The Journals of Captain James Cook. The Voyage of the Endeavour, 1768–1771, edited by J. C. Beaglehole (Cambridge University Press for the Hakluyt Society, 1955). One of many volumes by the world’s foremost authority on Cook, opened to show extensive commentary supporting the transcription.

Item 42

An Account of the voyages undertaken by the order of His Majesty for making discoveries in the southern hemisphere, and successively performed by ... and Captain Cook in ... the Endeavour. Drawn from the journals which were kept by the several commanders, and from the papers of J. Banks by J. Hawkesworth. Second edition (W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1773), opened at the same entry, 19 April 1770.

Item 43

H M Bark Endeavour; her place in Australian history by Ray Parkin (the Miegunyah Press, 1997). The most exhaus- tive and meticulous study prepared to date on Cook’s first voyage, and winner of the 1999 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards Book of the Year, opened at various journal writers’ descriptions of Botany Bay.

Item 44

Paul Carter, The Road to Botany Bay: an exploration of land- scape and history (Alfred A. Knopf, 1987). A re-evaluation of the origins of Australia based on diaries and other primary sources. Chapter one is a study of Cook’s naming practices and of subsequent explanations by scholars such as Beaglehole. It amounts to a brilliant interpretation of how the name Botany Bay ‘emerged’.

Display case lining

Three drawings from volume two of Parkin’s Endeavour study, showing (i) fore-&-aft sails, (ii) its profile showing lower masts, bow-sprit etc, and (iii) the running rigging.

Nettie Palmer

Nettie Palmer (1885–1964) was a leading Australian poet, essayist, literary critic and historian, and equally remembered for her partnership with the novelist, short story writer and dramatist Vance Palmer (1885–1959). After graduating in Arts and Education from the University of Melbourne in 1909, Nettie furthered her education via travel and formal study between 1910 and 1912 in London, Berlin and Paris.

Item 45

Handwritten diary/notebook, March 1910–September 1922, opened at 26 October (1910, London), where she describes a meeting of the Women’s Labour League.

Item 46

Signed issue of Nettie Palmer’s FOURTEEN YEARS: extracts from a private journal 1925–1939 (Meanjin Press, 1948), opened at the title page.

Item 47

Nettie Palmer: her private journal Fourteen Years, poems, review and literary essays, edited by Vivian Smith (University of Queensland Press, 1988), displayed for the cover illustration of Palmer. Vivian Smith’s ‘Editor’s Note’ (pp. 2–5) explains the full context of the journal, which he describes as ‘an anthology in journal form’ and of enormous importance to historians and those interested in the develop- ment of Australian culture between the wars.’

Item 48

Portrait of Nettie Palmer by Louis Kahan.

Diary-itis

Two remarkable things quickly strike any surveyor of diaries.

One is the staggering output of many writers, who in the most extreme cases seem to have done nothing else but write their diary. Some such as William Gladstone, also found time to conduct an extensive correspondence and serve as British Prime Minister! The American poet Arthur Crew Inman (1895–1951), whose 155 volumes produced over nearly 40 years encompass approximately 17 million words, would be among the most prolific. In his case, much of the diary content records the stories of hired ‘talkers’. John Evelyn, who to- gether with Pepys was among the best known 17th century diarists, kept his for 66 years, a period roughly similar to the evangelist John Wesley. The record, at least for published out- put, probably goes to Venerable Master Hsing Yun, the founder of the Fo Guang Shan Buddhist Order based at Kaohsiung. His published diaries total 44 volumes. Pepys’ decade of recording, which resulted in one and a quarter million words, pales by comparison, although we should remember that he stopped writing due to failing eye sight in 1669 aged 36, and he lived for another 34 years!

The other remarkable aspect, of course, is that publishing houses see sufficient interest in, and secure financial support for, the publication of the diarist’s daily record.

Item 49

A selection of published diaries by some of the world’s most prolific writers (Venerable Master Hsing Yun, Rev John Wesley, Samuel Pepys, William Gladstone, Ioannis Metaxas and Thomas Moore).

Raymond Priestley

The University of Melbourne’s first salaried Vice-Chancellor was the noted geologist, Antarctic explorer and University administrator Raymond Priestley (1886–1974). His brief term as Vice-Chancellor, 1935–1938, saw many initiatives, reforms and conflicts culminating in his resignation. That we know so much about his term is due to his extensive diaries kept during this period in Melbourne, and travel around Australia and to the US and UK. They are additionally important for the extras, including newspaper cuttings, letters, photographs and annotations added years later. The best of the 15 diaries is now available in a judicious and scholarly selection by Professor Ron Ridley released earlier this year by Melbourne University Press.

Item 50

Australian Diary 12, Raymond Priestley’s annotated typescript diary, 15 May–29 September 1938, opened at 30 June, his last day as Vice-Chancellor.

Item 51

The Diary of a Vice-Chancellor: University of Melbourne 1935–1938; Raymond Priestley, displayed for the dust jacket photo, ‘Priestley in geologist’s rig, 1936’.

Item 52

Antarctic Adventure: Scott’s northern party by Raymond E. Priestley (T. Fisher Unwin, 1914), an account based largely on the author’s diaries and including his own photographs.

War

Since Bill Gammage introduced the Australian War Memorial’s collection of soldiers’ diaries to a general readership, the per- sonal war diary has achieved almost sacred status in Australia, dwarfing their parallel official unit diary records and the limit- ed print run unit histories based on them. The personal diary is often self-published, but some, interestingly most by POWs (eg. Sir Edward Dunlop, Adrian Curlewis and Stan Arneil) have become minor classics.

Item 53

Carbon copy of official unit war diary, ADMS 8th Division Australian Imperial Force, October 1940.

Item 54

Personal diary 31 July 1914–12 March 1915 of Lieutenant A. P. Derham.

Item 55

The Broken Years by Bill Gammage (illustrated edition, Penguin Books, 1990). Original 1975 Penguin edition opened at diary extract describing shelling with gas.

Item 56

First world war gas mask.

Diaries and the internet

Since Bill Gammage introduced the Australian War Memorial’s collection of soldiers’ diaries to a general readership, the per- sonal war diary has achieved almost sacred status in Australia, dwarfing their parallel official unit diary records and the limit- ed print run unit histories based on them. The personal diary is often self-published, but some, interestingly most by POWs (eg. Sir Edward Dunlop, Adrian Curlewis and Stan Arneil) have become minor classics.

Item 53

Carbon copy of official unit war diary, ADMS 8th Division Australian Imperial Force, October 1940.

Item 54

Personal diary 31 July 1914–12 March 1915 of Lieutenant A. P. Derham.

Item 55

The Broken Years by Bill Gammage (illustrated edition, Penguin Books, 1990). Original 1975 Penguin edition opened at diary extract describing shelling with gas. Item 56 First world war gas mask.

Acknowledgements

The preparation of this exhibition has accrued many debts, beginning with its title (taken from Suzanne Bunkers and Cynthia Huff, editors, Inscribing the Daily: Critical Essays on Women’s Diaries, University of Massachusetts Press, 1996). All my staff in the Archives, Grainger Museum and Special Collections were willingly co-opted along the way, but I must especially acknowledge Stephanie Jaehrling, Leslie Caelli, Ian Morrison, Jane Ellen, Jason Benjamin, Liz Agostino and Brian Allison. And finally, warm thanks go to Susan Reidy and Jacqui Barnett from the Communications and Publications Section, and Maureen Brookes from the National Library of Australia.