Harpies

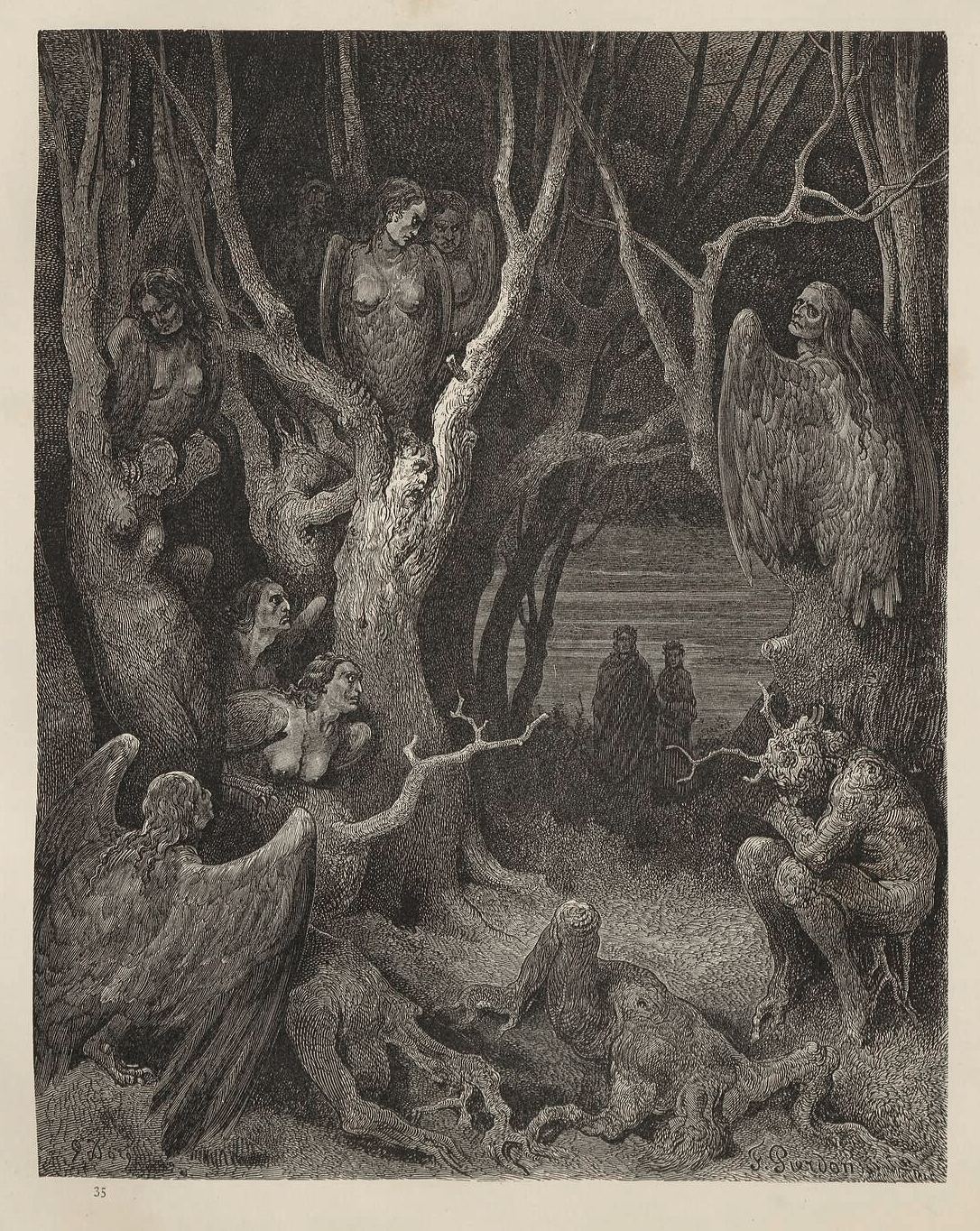

Harpies are found in Canto XIII of the Inferno, roosting in the Seventh Circle, in the Wood of the Self-Murderers. Here they guard, and eat, the people who have either attempted or committed suicide, resulting in their painful transformation into twisted, thorny, bleeding trees. The poem describes them as, "Wide-winged birds and lady-faced are these / With feathered belly broad and claws of steel; / And there they sit and shriek on the strange trees." (Inferno: XIII, 13-15)

Harpies are human-bird hybrids, generally female, and have been associated with various modes of ill-fortune in mythology, such as violent winds and storms. However, they are usually vehicles of punishment, working in league with the Furies to torment those who have offended the gods.

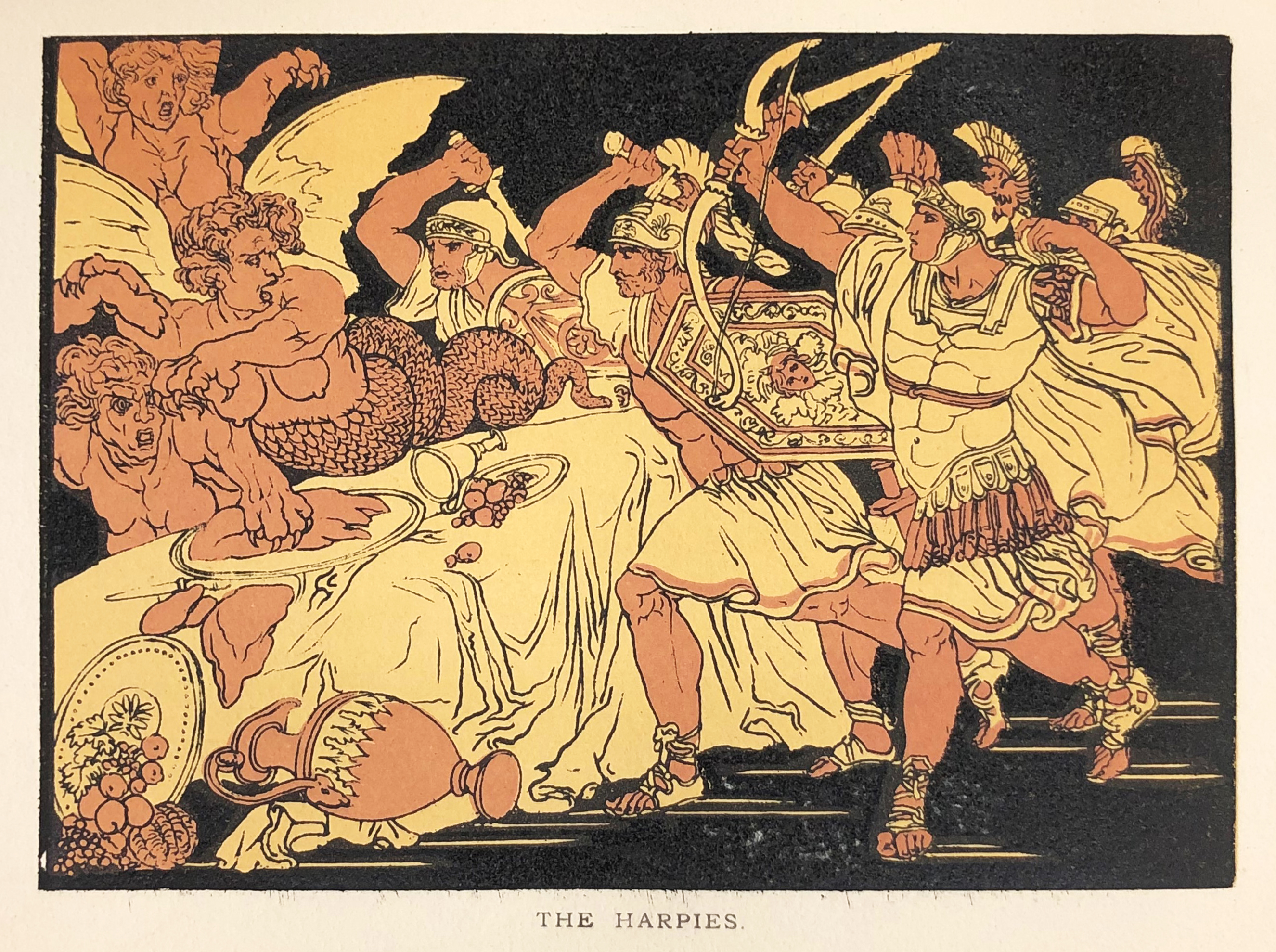

Their literary pedigree comes to the Divine Comedy, as much else does, from Greek texts such as Apollodorus' Library - in which they contend with Jason and the Argonauts when the heroes attempt to end their torment of King Phineas, as illustrated by Pinelli above - via Roman intermediaries, particularly Virgil: the beasts and their location among the bloody trees is based on the third book of the Aeneid.

In the Divine Comedy their role is to cause agony, feeding on the shoots and leaves sprouting from the suicides. Though distressing, the anguish they cause is nevertheless needed by the trapped souls: crying out in physical pain is the only way in which they are allowed a voice. Having expressed their grief by destroying their bodies, they are denied expression in death. Allegorically, just as the trees represent a misshapen mockery of the body they rejected in life, so too do the harpies who live in their branches. The relationship between the two is not lost in Dore's engraving below: the outstretched tree limbs in the lower left are a visual extension of a harpy's wing, and the faces and forms of the creatures are consistently elided with the forest, making the torturer and tortured appear one and the same - an apt allegory for self-hatred.