Presence and the Australian landscape

By Dr David Sequeira, Director, Margaret Lawrence Gallery, Victorian College of the Arts

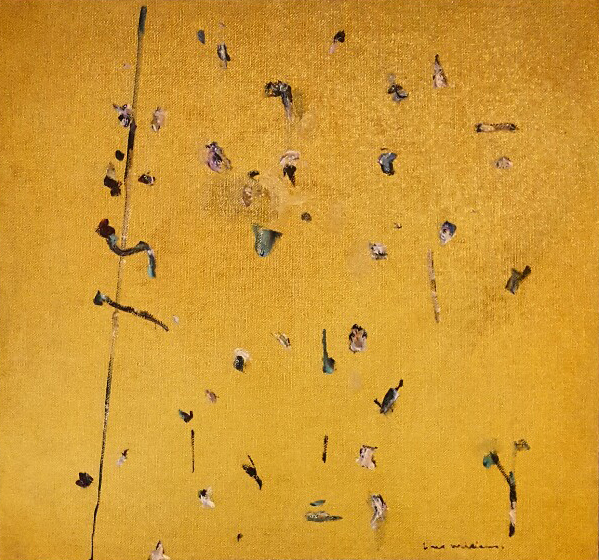

Image: Fred Williams, Hillside III (1968). Heide Victoria Collection.

Featuring work by artists including Frederick McCubbin, Clarice Beckett, Louise Hearman and Rick Amor, Presence, at Melbourne’s Margaret Lawrence Gallery, takes a look at how spirituality and the sublime manifest in depictions of the Australian landscape.

Comprising just seven works of art, Presence proposes neither an encyclopaedic nor an abbreviated overview of Australian landscape traditions. The exhibition is a highly personal selection of works borne out of an interest in exploring histories that are layered and nonlinear. With the exception of Michael Riley (1960-2004), the artists included in Presence are notable Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) alumni.

In 2017, the VCA is celebrating 150 years of art, a lineage that began with its predecessor, the National Gallery of Victoria Art School, and this selection of works results from a consideration of that history. At a time when the VCA is celebrating its past accomplishments and creating a new future, Presence is an opportunity to examine the nature of the institution’s relevance and contribution.

The National Gallery School was founded in 1867. Housed with the Museum, the State Library and the Museum of Art, the National Gallery School was part of a precinct dedicated to the cultural development of one of the fastest growing cities in the world.

In his 1988 essay The shaping of Australian Landscape Painting, the former director of the National Museum of Australia and National Portrait Gallery Andrew Sayers observed that:

“The late 1860s was a significant time for the development of the visual arts in Australia, and Melbourne was at the centre of that development. In that decade a truly critical culture emerged; such a culture was essential to the development of a visual art tradition.”

Presence can be understood as an investigation into the strengths and limitations of that “visual art tradition”.

Decolonising the Australian landscape

Not surprisingly, in the late 1860s there was no recognition of Indigenous art and history beyond the anthropological. The atrocities associated with colonisation in Australia, and the refusal to acknowledge the artistic value of cultures beyond Europe, contributed to this situation.

The unwillingness of the National Gallery School’s early artists and academics to engage with the richness and complexity of Indigenous art denied it a presence in Australian art history for many years. Australia had to wait until the postmodern theories of the 1980s penetrated traditional orthodoxies of the academy before embracing its Indigenous artists and art practices as an integral aspect of visual art discourse.

No-one in 1867 would have predicted the extraordinary output and international acclaim of Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Rover Thomas, Queenie Mackenzie, Paddy Bedford or George Milpurrurru, none of whom, of course, had ever attended an institution like the National Gallery School.

A large-scale projection of Michael Riley’s film Empire (1997) forms the central core of the exhibition, around which hang works by Eugene von Guerard, Frederick McCubbin, Clarice Beckett, Fred Williams , Rick Amor and Louise Hearman.

Examined individually, each work can be understood as an individual response to an experience of landscape. Collectively this grouping speaks of change and transition, of an evolving visual language and a multiplicity of ideas and points of view. Emotionally charged, the conceptual ambitions of each work extend beyond documentation of a range of topographies.

As art historian Simon Schama asserted in his 1995 book Landscape and Memory:

“Landscapes are culture before they are nature; constructs of the imagination projected onto wood and water and rock […] once a certain idea of landscape, a myth, a vision, establishes itself in an actual place, it has a peculiar way of muddling categories, of making metaphors more real than their referents; of becoming, in fact, part of the scenery.”

In Empire, Michael Riley imbues a rural Australian landscape with the haunting residue of missionary influence. Commissioned in 1997 for the Cultural Olympiad Festival of the Dreaming, Empire is a visual essay that presents an ancient landscape as both microcosm and macrocosm.

Riley’s depiction of climactic effects – a dried carcass, dead trees, red cracked earth, clouds emerging and dissolving – suggests a spirituality and endurance that transcends time.

Christianity and colonisation are fleeting moments, consumed by the elements, within the millennia of Riley’s Indigenous history. Antony Partos’ grand sweeping score, performed by the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra and punctuated by the sounds of thunder, wind and rain, is mournful and apocalyptic.

Riley presents a landscape that is expansive and redemptive, a potent reminder of Indigenous understandings existing centuries before the 150-year celebration currently underway at the VCA.

Plein to see

In 1870, Eugene von Guerard (1811-1901) was appointed Master of Painting at the National Gallery School and Curator of the National Gallery of Victoria. Painted en plein air style, From below the lighthouse, Cape Schanck, Victoria (1873) is a small study for use in the development of more substantial studio works.

Painted from direct observations of nature, these studies allowed von Guerard to record the composition, light and colour of a scene with relative speed. The son of an Austrian court painter and trained at the Dusseldorf Academy, von Guerard brought a German Romantic sensibility to depictions of the Australian landscape.

Here, his chosen site is the coastline, a meeting point of land and ocean; rock and water where the constant splashing of the ocean against the stone creates spectacular and treacherous cliffs.

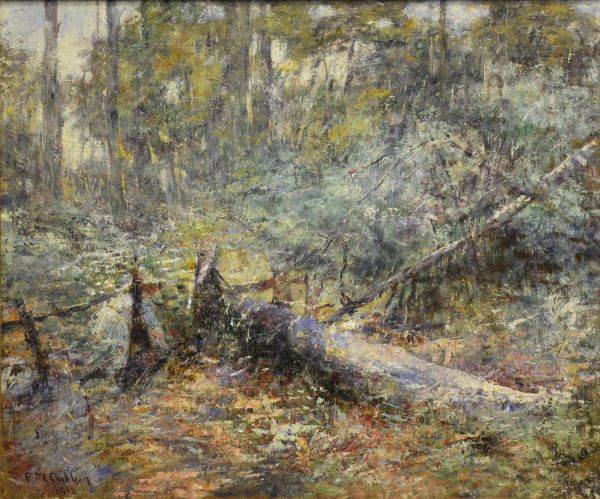

Frederick McCubbin (1855-1917) was one of Von Guerard’s pupils and later taught at the National Gallery School. McCubbin’s choice of site for the painting included in this exhibition is deeply personal.

The work, At Macedon (1913), was painted in or nearby his property at Mount Macedon and the figure is likely to be that of Kathleen, McCubbin’s daughter who was seven at the time. In the 2013 book Wilbow 25: 25 Years of the Wilbow Collection of Australian Art, 1988-2013, curator Jane Clark described the girl as embodying “the artist’s vision of the landscape as a place of natural innocence: a symbol of youth in deliberate counterpoint to the decaying trunk of the fallen forest giant”.

Painted just four years before McCubbin died, At Macedon demonstrates the influence of European impressionism. The dazzling effects of colour and light on the land and its foliage are masterfully textured with a palette knife, the painting, while clearly a landscape, has an abstract quality.

Like McCubbin, Clarice Beckett (1887-1935) seemed more interested in atmospheric effects than topography. Beckett, a student of McCubbin at the National Gallery School before studying further under Max Meldrum, painted sites close to her home in the Melbourne suburb of Beaumaris.

Enveloped in a misty haze, Beckett’s seascapes and street scenes appear mysterious and ethereal. Beckett’s work, and in particular Half Moon Bay (c1930), can be understood as a precursor to abstraction and more specifically minimalism.

As curator Tracey Lock-Weir suggested in 2008’s Misty Moderns Australian Tonalists 1915-1950, this work demonstrates “her ability to surrender all she knew and uniformly paint her world simply as what she saw: tone, form and colour”.

By reducing the landscape to these three elements – tone, form and colour – Beckett created blurry fusions of land, sky and sea that embody a sense of dreamlike other worldliness.

Beyond the horizon line

Fred Williams’ (1927-1982) approach to landscape seems grounded more in form than subjectivity. Like Beckett, Williams had an interest in exploring the expressive quality of tone.

But Williams extended this interest by creating a visual vocabulary of calligraphic brushstrokes and knots of paint that refer to trees, earth and rock features.

In Hillside III (1968), this style of mark making is applied without the presence of a horizon line. Curator of Australian Art at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) Deborah Hart suggested in 2011’s Fred Williams: Infinite Horizons that “Williams’ special talent was abstracting from the real or, as he put it, seeing the world ‘in terms of paint’”.

The result is a distilled landscape with no specific point of focus that encourages the viewer to scan across the entire surface of the canvas.

Rick Amor (b. 1948) is a masterful and disciplined painter and draughtsman, profoundly impacted by a range of artists and movements from across several centuries. Combining these influences with his rich personal iconography of Melbourne’s streets, parks, buildings and bridges, Amor creates imagery that is at once both familiar and strange.

The articulation of moments of stillness and silence within urban spaces has been a constant theme for Amor.

In Summer Morning Lucerne Crescent Alphington (2012), he reveals his own suburb still in its slumber. The only human activity is a hot air balloon floating in the distance. Amor casts a sense of mystery by shrouding his neighborhood in the dream-like warmth of half-light and shadows.

Only a few hours from night but not quite yet day, dawn is an “in between” time – a time of transition. Painted en plein air not far from his home and studio, Amor immersed himself in this in between time in order to depict it.

Natural phenomena have featured extensively throughout Louise Hearman’s (b. 1963) career. Passages of intense radiance and darkness are used to create imagery that is often haunting, unsettling, ambiguous and emotionally charged.

In Untitled #480 (1997), the dissolution and accumulation of clouds seems to allude to the supernatural. Hearman’s melancholic velvety blueness transcends space and time; the emergence of light is both mellow and apocalyptic.

Preferring not to presuppose or interfere with the viewer’s interpretation of her imagery, Hearman’s works are untitled.

Her mystical arrangement of clouds and light appeal directly to the human psyche, granting the viewer the opportunity to allow a range of associations to emerge from the subconscious.

In 1998, Andrew Sayers curated a major exhibition at the NGA examining two great traditions of landscape painting of the 19th century – those of Australia and the US – and explored how artists steeped in “old world” traditions reacted when confronted by landscapes of the “new world”.

In the catalogue essay he noted that “it was the National Gallery School more than any other institution that contributed to the development of a group of artists who came to see themselves as pioneers of an authentic Australian painting and who were seen by subsequent generations as the founders of the Australian visual art tradition”.

While Presence includes work by notable Gallery School alumni, and certainly serves to illustrate Sayers’ claim, its intention is not solely to highlight these artists’ specific accomplishments and contributions. More importantly, it seeks to expand our consideration of Australian art history – engaging both Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives – and indeed the 150 year history of VCA Art and its predecessors.

Presence runs at the Margaret Lawrence Gallery, 40 Dodds Street, Southbank, Melbourne until 1 April 2017. More details.