Gareth Sansom, the transformer: interview

By Fiona Gruber

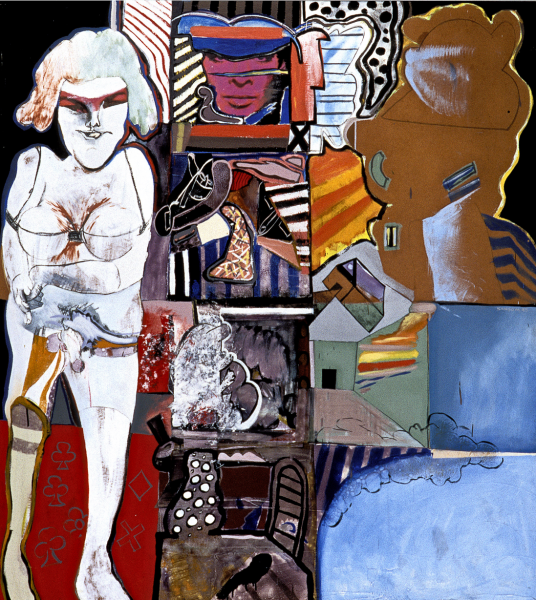

Gareth Sansom, The Seventh Seal (i) (2007) [Detail]. Oil and enamel paint on canvas, 183.0 x 213.0 cm. Private collection © Gareth Sansom/Administered by Viscopy, 2017.

Gareth Sansom is being rightly celebrated as one of Australia’s eminent visual artists with a major exhibition, and an Artist to Artist event at the Victorian College of the Arts. Arts journalist Fiona Gruber had a candid chat with him.

On 2 October, artist and former Dean of VCA Art at the Victorian College of the Arts Gareth Sansom will be at Federation Hall, on the VCA’s Southbank campus in Melbourne, in an Artist to Artist event with the new Director of the VCA, and eminent artist in his own right, Professor Jon Cattapan. It speaks to the esteem in which Sansom is held that this coincides with Transformer, a major retrospective of Sansom’s career currently underway at the National Gallery of Victoria.

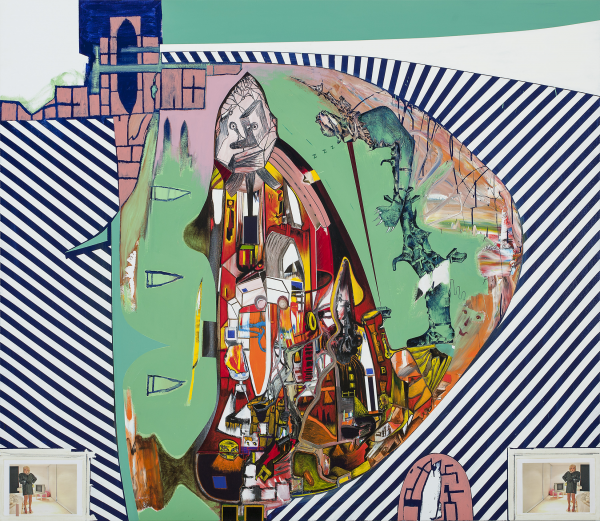

The first thing that strikes a visitor to Transformer is how vivid the work is and how there’s a sizzle and dazzle to almost every painting. Alongside this colour-fest is a realisation that here is an artist who hit his straps early and has kept going with brio in a career spanning more than 50 years.

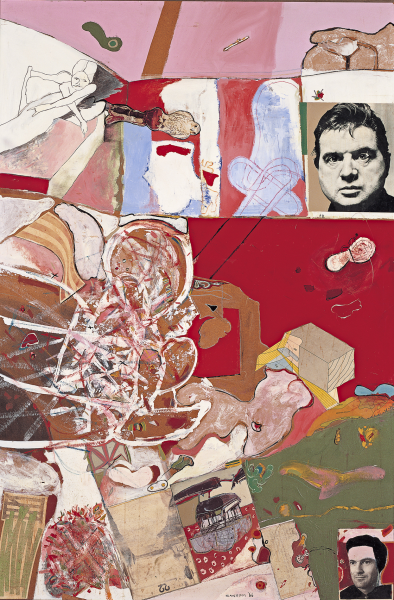

The broad flat planes of colour, broken by clusters of frantic busyness are there in works from the early 1960s, as are the fractured faces and twisted bodies at odd, broken angles. There are the exuberant scatterings of small images and symbols that nod to an iconography that is both very personal and one that is plugged into a fascination with sex, gender, death, history and popular culture.

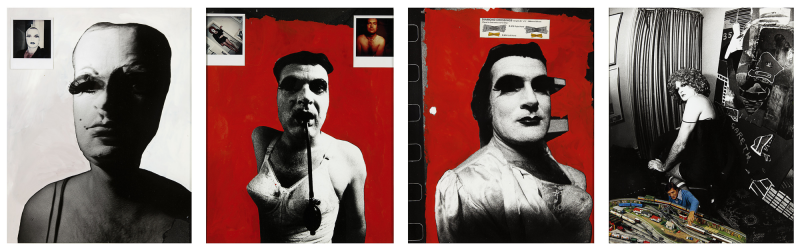

Anchoring much of this is his provocative, often confrontationally, use of collage. Clippings from sensational news stories, images of contemporary and historical characters and many images of himself in various guises, create a visual diary that prefigures today’s obsessive confessional and quotidian tendencies on social media.

As the NGV’s curator of contemporary art Pip Wallis writes in the exhibition catalogue’s opening essay: “Sansom has forged a body of work at a moment of history between the great monolith of modernism and the cacophony of post-modernism.”

There are more than 130 works in total, paintings, drawings, prints and photographs on Masonite, canvas, paper and card as well as a dungeon-like room dedicated to masks. There’s a lot of Goon-like humour in the work and a lot of grotesquery and darkness too.

When I talk to Sansom, it’s a couple of days after the opening and he’s both relieved to have got it out of the way, and buoyed by the reception from the invited crowd.

It was a big night, he says; a group headed off afterwards to inner-city bar Madame Brussel’s (named after a 19th-century Melbourne brothel keeper) and its back room, the Munich Man Cave. It’s a good choice; the club’s playful riff on sex culture and gender norms echo Sansom’s own 50-year obsession with subverting stereotypes.

Sansom was exploring sexuality and gender way before it became a mainstream preoccupation and his work features transvestites and photos of himself dressed as a woman, often a sexually-inviting one, in scanty lingerie, with heavy make-up and luxuriant wigs.

The Blue Masked Transvestite (1964) is a defiant and celebratory piece of painting, while Bates Motel (2011) features a fractured form with two small photos of a bouffant Sansom in miniskirt at the bottom of the canvas. He stripped back one of the family bedrooms to get the stark motel feel, he explains.

Far from being about an erotic charge, his aim has always been about challenging social norms.

“People who know me know that my interest was not in transvestism but exclusively trying to create a contrast to my super straight background. I like the contrast between ideas of clean and unclean or unhealthy. It’s theatre, it’s playing. I’m more interested in closet lives,” he explains.

Madame Brussel’s was full of old students, he continues, and it was delightful catching up.

As the former Head of Painting at VCA, and later Dean of VCA Art, a commitment spanning 13 years, he says he revels in diving back into creative debate, but hastens to add that he’s no “Mr Chips” (a fictional schoolmaster who lived through his pupils). He quit the day job in 1991 to paint full-time, aware that if he didn’t, he’d have a life of regrets.

How does he find viewing such a large body of work over such a time span?

Confronting, he says, especially seeing himself age through the works. “I find my 24-year old self hard to recognise,” he says. ‘I have thousands of photos on my computer and I’ve gone through them all and then I look in the mirror and it’s a shock to see myself now, at 78.”

He’s also a bit bemused by the young Sansom’s appropriations and rough early style.

“I look at earlier work and I think ‘how the hell did I do that?’ I was borrowing but I was also assimilating; Bacon, Bruegel, Bosch. It’s always been my mantra; if you want to pinch ideas you have to subsume them into your work.”

He also knows he was less skilled as an artist back then.

“My technique has evolved. The early works are aggressive and crude,” he says, and it took years to develop the skills to paint in any way he wanted.

He works a bit more slowly now but ideas still come easily and the break from painting while setting up the exhibition makes him champ to get back to his work base in Sorrento to experiment with new ideas.

He often has more than one work on the go simultaneously, he explains, and they glower at each other from opposite sides of the studio, waiting for moments of inspiration.

Sansom’s description of how he paints suggests a bandit out to ambush a canvas.

He sidles up to the blank surface, circles it, and when the time is right he’s goes right in, but there are no plans, no preliminary drawings, nothing “contrived”. How a painting ends up is a mystery at its beginning.

“I’m just waiting for when the solution just appears and the painting controls me,” he says.

Sometimes last-minute flourishes can make the work sing, as well as give the painting its title.

Transformer (2016), the work that gave the NGV exhibition its title, came about because, as he felt he was approaching the end of the painting, he stuck the vinyl of Lou Reed’s LP of the same name to the canvas.

“It worked, so I painted spikes coming out of it,” he explains. Not everyone shared his elation, however.

“My wife’s not happy,” he says. “The record came out of her collection.”

Sometimes he feels his Dr Jekyll rationalism slipping into “mad Mr Hyde”, where he “takes pictures to the edge of the cliff and if you muck up you fall over.” You can scramble back again, he says, but sometimes a beautiful bit of painting, done in the first couple of days and kept pristine over months of hard work, gets painted over at the last moment.

So how does he know when a work is finished?

“I know it’s finished if I continue I wreck it,” he says.

There is, of course, no suggestion that Sansom’s work – as a body – is finished.

Tickets are free but in high demand for Gareth Sansom’s Artist to Artist conversation with Jon Cattapan at the VCA on 2 October, so book now for a chance to hear two of the country’s major senior artists.

Artist to Artist: Gareth Sansom is at Federation Hall, Southbank, on 2 October, 5.30pm–6.30pm. Free event, bookings essential. More details.

See also: Jon Cattapan: a portrait of the artist as a new director