David Noonan: making art in a dark and quiet place

By Fiona Gruber

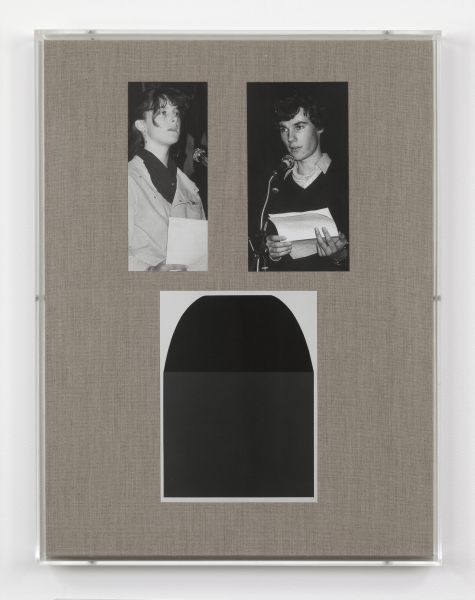

David Noonan’s work at the Victorian College of the Arts 9 X 5 NOW exhibition, 2017. Untitled. Paper collage, UV protective varnish.

David Noonan’s dynamic collages and cut-out sculptures have made his name as an artist internationally. But his new project promises to be moving, in more ways than one.

Visiting David Noonan’s East-End studio in London on a hot summer’s day, the first, rather disappointing thing that strikes me is the absence of art. There are none of his filmic, collaged canvases or cut-out sculptures. Only one large work sits propped with its face to the wall; it’s in for repair, he says.

Noonan is mildly apologetic; he’s in the middle of making a film – A Dark and Quiet Place – and there is nothing to be seen except a loose book of stills.

Other artists’ studios would contain the tools of the trade, the accumulated detritus of years of habitation, but Noonan is a neat and methodical man. His space has a desk, a sofa and a bookcase. His assistant, Australian artist Matthew Berka, sits at a computer editing the soundtrack to the aforementioned movie, which is due to screen in August. All is calm efficiency.

Noonan, born in Ballarat in 1969, has made his name internationally as an assembler of stills, a collage of black and white photographic images that conjure up a tantalising range of possible narratives.

So, if he were working on a show, I want to know, what would his studio look like?

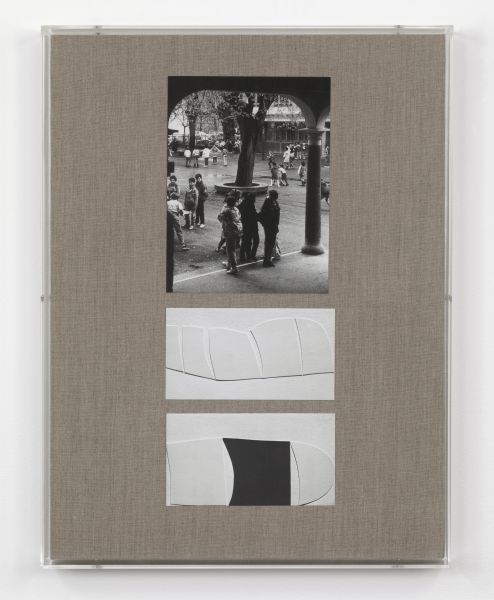

There’d be reams of screen-printed linen, he explains, torn up and hand collaged, and the whole process of making a work would go through distinct phases.

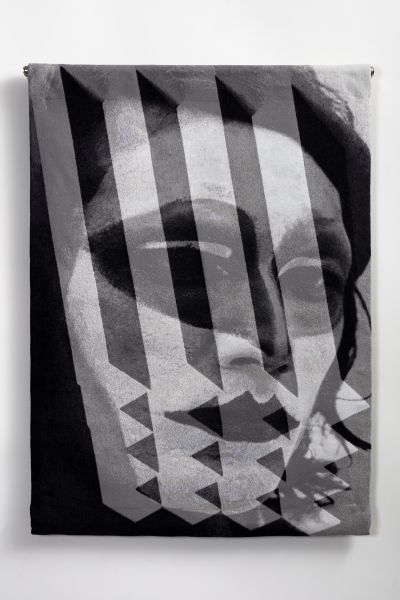

“Each picture goes through a lot of processes to get to the final piece, beginning with the scanning and combining of images. Then there’s the mechanical process of screen printing, often using four or five people to make the prints because they are quite large, so there’s the element of the hand within that … and then they come back to the studio, where they’re assembled into the final pieces, and within that process they often change as well. Most of the pictures may be 20 metres of different images on linen and then I cut them and tear them and collage them in the studio.”

A Dark and Quiet Place is an extension of Noonan’s visual language. It will be between 15 and 20 minutes long, utilising a range of photographic images from his extensive ten-year deep archive, images that never made it into his pictures but are drawn from the same dramatic world.

“A lot of it deals with theatrical scenarios and the relationship between abstraction and figuration,” he explains.

Is movie an accurate term? After all, it’s a series of stills.

“Ah yes,” he says. “But they’ll be in constant movement. Most of my pictures are drawn from the language of film, using superimposition or transition or dissolve; so in essence every image is two images superimposed.”

A Dark and Quiet Place explores the world of the stage, its props, sets and design, and the actors who inhabit the realm of make-believe; what he’s after, he says, is a mood, an atmosphere that “draws you into another dimension”.

Noonan’s archive is key to the whole enterprise; it’s extensive, thousands of images neatly filed in boxes, on hard-drives and in his library, some of which is on display in the studio. I flick an eye at the titles, pick a few at random; books on stage design, on dance, on masks, on Sweden, on Japan, and a thick section on owls – a recurring avian motif in Noonan’s work.

His library aside, where does he find his images?

“I trawl through a lot of art shops, second-hand bins of old catalogues and often find very obscure artists,” he says. “I’m not interested in using images that are recognisable. In my more recent work I’ve quoted designs and obscure abstract painting and sculptures, people who have almost been relegated to the dustbin of history.”

He often doesn’t even bother recording the artists’ names, he confesses. It’s all about mood and states of being with Noonan’s work. A lot of it evokes a dimly distant idea of modernism, the past’s idea of the future. The language may utilise the grammar of those great visual mediums of the 20th century, photography and film, but the staginess evokes a far more ancient idea of the theatre. Although he probably dislikes the term, there’s a very strong whiff of the retro in all of his images.

An interview Noonan did in 2006 for the international art magazine Frieze, in which he was asked to discuss his favourite films, comprised movies mainly from the 1960s and 70s: Jean Luc Godard’s Alphaville, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s decadent classic The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant; the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, Alejando Jodorowsky, Werner Herzog.

Why so few recent films?

“I suppose they were the films that were very formative, growing up,” he says, although most of those films were made when Noonan, born at the end of the 60s, was still watching Play School.

Home was the gold-fields town of Ballarat, not a hotbed of the avant-garde, but there were pockets of creativity. His life was changed by a music and video store called Black Swan Records. He ended up working there and watched every art house movie it possessed.

He left his “ghastly” Catholic boys school as soon as he could and enrolled in the art course at the Ballarat School of Mines. It was an inspiring time, he says, with every art form covered and treated with passion and rigour. He learnt ceramics, photography, painting and knew that he had to be an artist.

After a stint at an ashram in India, he did a BA at Ballarat University before enrolling for an MA at the Victorian College of the Arts.

He moved to London for a period in the mid-90s with his long-time friend Jennifer Higgie, co-editor of Frieze.

They were both doing the painting MA, and both were nominated for the VCA’s coveted Keith and Elisabeth Murdoch Travelling Fellowship. They made a deal: if either won, they’d buy the other a plane ticket to London. Higgie scooped the award in 1994 and duly bought Noonan a ticket. They shared a flat, worked in cafes, dived into the art scene, made work when they could. It was an exhilarating time and, while Higgie stayed on and moved into art journalism, Noonan returned to Melbourne.

He loved the Melbourne scene and especially the artist-run spaces. But despite being taken on by esteemed gallerist Roslyn Oxley and getting some interest from overseas, travelling was hard.

He was in his mid-30s when he made the leap to return to London 12 years ago, realising, “that you’re not going to be visited by a curator from the Tate in your studio in Footscray”.

Noonan’s been living in the UK since 2005; he made the move at the height of London’s East End boom. The place was “on fire” he says, with hip new galleries popping up every week. Everyone living in his street in Bethnal Green, he says, was an artist.

The borough of Tower Hamlets had as great a concentration of artists as Berlin but rocketing house prices has since killed the scene, many of the galleries have closed and artists have moved further out, even, he says to distant seaside Margate on the south coast, a briny melancholy dump transforming itself into a new artistic Jerusalem.

Noonan still lives in the East End with his artist wife Renee So and four-year-old son. He moved his studio from Bethnal Green to the still-arty but less expensive Homerton two years ago, a shift that triggered the exploration of his extensive archive and led to the film. He comes back to Melbourne every 18 months or so and, while he has galleries in London and Brussels, he’s also still firmly part of the Roslyn Oxley stable.

“The art world is going through a sea change,” he says, adding that London is now as corporate as New York, auction houses have muscled in on the gallery scene and can screw up an artist’s career by underselling their work and Brexit has thrown a lot of foreign artists’ futures in the UK into jeopardy. “It’s a very alarming and depressing time in this country but at the same time it’s shaken things up and made people think about the issues.”

But these are dark thoughts; he’d much rather talk about the London premiere of A Dark and Quiet Place in August at Stuart Shave Modern Art and the directional sound “shower” that will surround the viewer above a specially-designed bench.

“I feel my work is undergoing change,” he says. “There’s been a ten-year period of working with screen-printed collages, and if it feels too comfortable and familiar, it needs to change.”

The political climate is another reason he’s moved away from making material pieces. “I decided to step into a more reflective time about what making means. I like to think of the film as something that will wash over the audience, that allows them to enter a particular space and atmosphere that is almost meditative.”

And after the premiere, I ask, what’s next?

“Another film,” he says immediately. “Creatively this has been incredibly stimulating.”