Cold comforts: Frieze editor Jennifer Higgie in interview

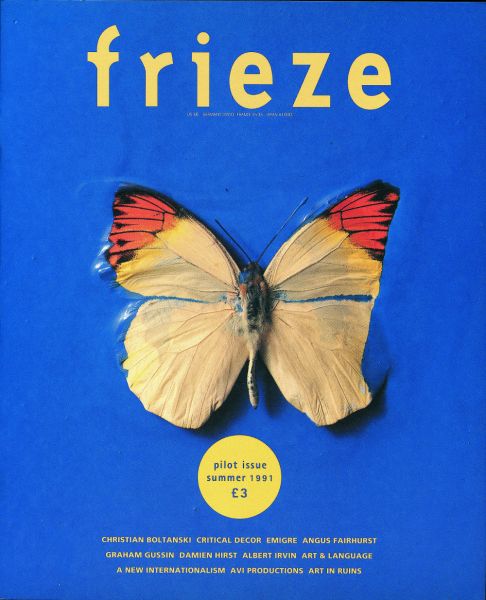

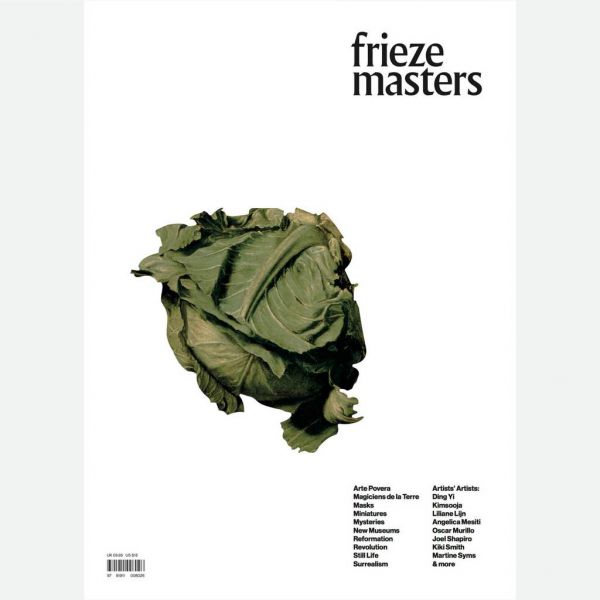

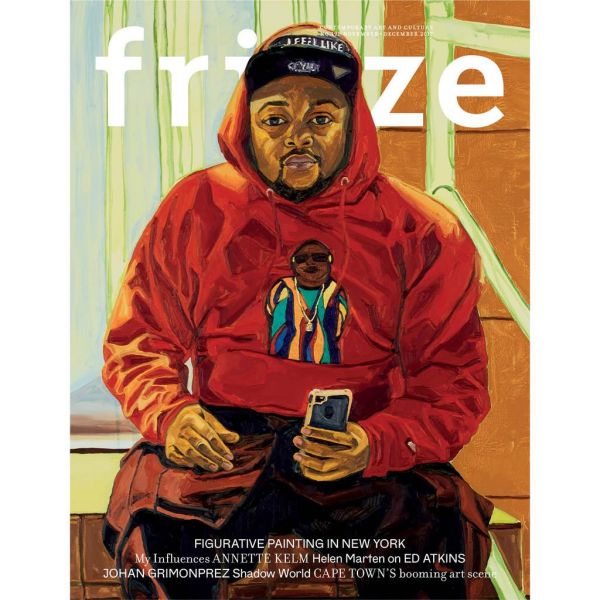

Frieze magazine covers. Source: frieze.com

The Victorian College of the Arts alumna talks life at the helm of a revolutionary arts magazine.

“Imagine culture without art – it would be moribund,” says Jennifer Higgie.

We’re sitting in an attic office at Frieze magazine in London’s East End, a space thrumming with activity. Higgie – a Victorian College of the Arts alumna – is reflecting on her career at the magazine and in the art world at large over the past 20 years.

As co-editor (with Dan Fox) of an international contemporary arts magazine, Higgie, who is also a novelist and screenwriter, says she has always seen art as part of a bigger conversation, and that Frieze’s editorial policy reflects this.

“Our tagline is contemporary art and culture and a look at the relationship between visual culture and culture more generally,” she says.

Frieze’s mantra is that “the most complicated ideas can be expressed simply and clearly, and that you can use humour; reading about art and culture should be pleasurable as well as informative.”

Aiming for gender balance is also important: Higgie’s Instagram feed is dedicated to introducing women artists from across the ages to a wider public, to emphasise that, despite the enormous obstacles in their way, there have always been women making art.

It would be great to see that emphasis reflected in the pages of Frieze, she says, but it’s difficult. “We do work very hard to have gender balance but it is hard because most commercial galleries don’thave a gender balance.”

But there are hopeful signs. Higgie cites Tate Modern’s new director Frances Morris’s re-hang of the collection.

“It’s the first time a major gallery has had 50% women,” she says. “It also has a far greater geographical reach and representation than ever before.”

Frieze began in 1991 in Soho with six staff. It was founded by Amanda Sharp and Matthew Slotover (who retain overall control of the magazines and associated fairs) and artist Tom Gidley.

They had seen a gap in the market, says Higgie, that tapped the explosion of artistic creativity in London following on from the YBA (Young British Artists) movement.

In 2003, Sharp and Slotover set up an annual art fair, Frieze London. It differed from other fairs, says Higgie, by running a series of talks and events alongside the buying and selling of art.

These days, alongside Frieze magazine, which is published eight times a year, the company publishes Frieze Week and Frieze Masters (which Higgie also edits) to coincide with its annual art fairs.

Frieze New York was founded in 2012, and has offices in Berlin and New York and a staff of 60. In 2016, Frieze Academy was launched, a year-round program of talks and courses in which Higgie is also involved.

Higgie arrived in London in 1994 with her close friend and fellow VCA Art graduate David Noonan. They’d both been contenders that year for the VCA’s Keith and Elisabeth Murdoch Travelling Fellowship and had made a deal that, if either won, they had to shout the other an airfare from Australia to London.

Higgie won it, duly coughed up for Noonan, and they ended up sharing a house, creating art whenever they could, and working as waiters in the same restaurant.

Before leaving for the UK, Higgie had also been a “secret writer” about art, and she found being in London, so far away from home, liberating. “You could humiliate yourself without anyone noticing,” she says.

In 1997 she successfully submitted a review to Frieze on an Andy Warhol exhibition, and after a few more articles found herself reviews editor.

In the intervening years, the art market – and London’s place within it – has changed, alongside a growing awareness of what it means to be an artist in a globalised environment.

“Today there’s a real professionalism, which has its good and bad sides,” she says. “You visit art schools and they have their business-cards ready, they have a business scheme. Their work looks pristine and I think, ‘My god, we were so chaotic’.”

Higgie’s father was a diplomat. She was born in Vienna and grew up in Paris and the UK before the family returned home to Australia. In 1990, following studies at the Canberra School of Art, she began a Masters in painting at VCA and became involved with blossoming artist-run initiatives such as Basement Project and Temple Studio.

“There was such a wonderful energy,” she says. “You could live quite cheaply in St Kilda or Fitzroy and be part of an artist-run space and everyone would come. I’m so grateful to have this grounding.” She remembers, and praises, VCA Art staff such as Norbert Loeffler and Tim Bass for their rigour and thoughtfulness.

Back then, she says, there was a more doctrinaire view of what counted in contemporary art and what was beyond the pale. Today, by comparison, there’s “an absolute openness about the way someone might want to make art. Whether you’re a painter or a post-internet artist or a filmmaker, the art world can accommodate it.”

“There’s also a far greater awareness that it’s not just about London, New York and Berlin, and that those centres are not necessarily creating the most important thinking.”

Still, place matters. Though Higgie thinks Australia has a fantastic art scene, which she covers editorially whenever she can, she suggests artists seeking international recognition should give serious thought to placing themselves where the international curators are.

For those just starting out, she has some pertinent advice. “Don’t get too preoccupied by the questions, ‘When will I get a gallery? When will I make money? When will I be published?’” she says. “If you remain deeply interested and engaged with what you do, the rest takes care of itself.”

It may also, of course, take some time. Higgie was a waitress for 15 years on and off. “You can’t commit to being an artist or a writer unless you’re willing to fail,” she says. “You have to be devoted and not be able to imagine a life without it, otherwise you’d do something easier.”

Higgie, who published the novel Bedlam in 2006 and wrote the screenplay for the 2007 feature film I Really Hate My Job, recently embraced a new challenge, after developing an itch to draw again.

Her book for small children, which she illustrated and wrote, is called There’s Not One and was published in 2016 by Scribble, an imprint of Melbourne publishing house Scribe. A meditation on being unique and also part of a wider community, it was shortlisted for the 2017 Australian Book Design Awards. She’s currently writing and illustrating a second story, called I’m so Confused.

The importance of art, its capacity to effect genuine transformation, is clearly of interest to Higgie. An article in the March edition of Frieze examined art and protest by inviting 50 artists from 30 countries to comment on how important they found art as a conduit for change.

“It made me realise that there’s no real consensus,” she says. “Apart from the idea of the imagination as being central to how we live as human beings, how we cope with the world and make sense of it. In places of conflict, art gives you the possibility of change. It’s a reflection of where we are and how and where we might be.”

After 20 years, she says, her enthusiasm for her job is undiminished. “It’s exhausting and relentless and [having offices in three countries means] Tuesday editorial meetings can be a logistical nightmare. But it’s never boring. I’m passionately committed to art in all its myriad forms.”