Artistic encounter: Jon Cattapan and Ian McLean

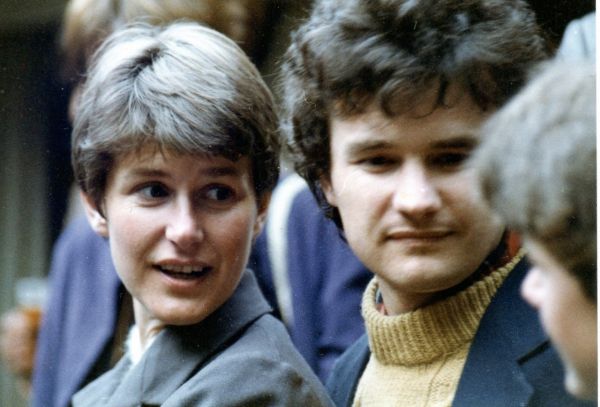

an McLean, late 1970s, on Grand Tour in Europe. Image courtesy of Ian McLean.

Professor Ian McLean studied at the Victorian College of the Arts in the 1970s, and was recently appointed as the Hugh Ramsay Chair of Australian Art History at the University of Melbourne. Artist and Deputy Director of the VCA Professor Jon Cattapan interviews him on his journey from artist to art historian.

Jon Cattapan: Ian, the seventies were a particular time. The Labor prime minister Gough Whitlam had set in place a free tertiary education for students like us, and there was a sense of trying stuff out. What took you to the Victorian College of the Arts in 1976?

Ian McLean: I still remember my elation on the evening of December 2, 1972, when the news came through of Gough’s election. Overnight Australia seemed a better place to be, but not Queensland, where I lived, and where Gough was a distant light in the long Dark Age of Joh [Bjelke-Petersen, National Party premier of Queensland].

Free education was just a small part of it. I remember Gough for so many other things: Blue Poles, the Aboriginal Arts Board, pouring soil through Aboriginal rights activist Vincent Lingari’s hands in that famous photo staged by photographer Mervyn Bishop. Before Gough was elected I was a teenage political activist with a theoretical bent, reading Marx and Hegel, Fanon, Eldridge Clever, and Chomsky, and talking to old communists in the Valley about the 1930s and 50s.

I studied to be an art teacher. Two of my lecturers, Bill Robinson and Betty Churcher, really opened my eyes to the power of art. Betty was my first real mentor. She and Roy (her husband) had an open house, or so I thought, where there invariably seemed to be an artist visiting from the south, or even New York. There was art all over the walls. For me, as a kid for whom art was not in the family genes, it was like stepping into a wonderland.

Otherwise, there wasn’t much happening in Brisbane, except for Joh’s regime, the occasional riot and Ray Hughes' art gallery. Roy exhibited new art from the south – Allan Mitelman’s poetic minimalist scratchings were a favourite – and a few locals. That’s where I met artist Bob MacPherson. His exhibition of large Black and White monochrome paintings at the newly opened Institute of Modern Art in 1975 blew my mind.

I was hungry for more, and no doubt pestering Betty with my naïve enthusiasm. She chased me away from Brisbane, advising me to study painting at the VCA and art history at Monash University under Patrick McCaughey. Like Betty, I was as interested in both. MacPherson’s monochrome paintings were hanging in the corridor of the Visual Arts Department at Monash.

Jon Cattapan: I remember visiting the VCA on a number of occasions while studying at RMIT. By comparison, the VCA, located behind the NGV, seemed very intimate, very laid-back, and rather privileged. What was your experience as a student?

Ian McLean: There was a very small intake, and we were told on the first day that we were the crème de la crème. It made me snigger. Coming from the back blocks I felt like an imposter, but it was where I wanted to be.

It was the best and worst of times to be at art school because of the conceptualism virus. Unlike Betty and Bill, who had escaped that virus, the VCA teachers didn’t seem to know what to teach except for technical things. I remember getting frustrated with being taught the finer points of stretching a canvas, which was not why I had left Brisbane.

So much seemed to be unsaid, as if certain secrets were being deliberately withheld, or as if the things worth saying couldn’t be articulated. But that’s also why it was the best of times. The ennui created a sense of shared struggle for meaning. I think that was the year that American sculptor Carl Andre came through the school in his ubiquitous overalls.

I admired Carl’s art because it made me think. He was a conceptualist of a materialist bent. Another American at the VCA, Bill Kelly, who was head of the art school, was a conceptualist painter of a realist bent. Kelly also donned the uniform of the worker and in his King Gees could have, like Andre, been mistaken for the cleaner or groundsman.

Bill Robinson and Betty Churcher were real teachers. They showed you what art did and how it did it. The VCA undid all of that – it was as if art had lost its bearings. Things were different at the Prahran Faculty of Art (which merged with the VCA in 1992), where everyone was welding steel or making paintings and art didn’t seem a problem at all.

Jon Cattapan: The VCA at the time had a reputation for progressive conceptually-inclined work. But what were you interested in? What were you making?

Ian McLean: As I remember it, the conceptualism at the VCA was more an atmosphere or mood, not a program. You felt it most in the lecturers’ lack of direction rather than the student’s aspirations. Most of the students were uninterested in conceptual art. About half the painting students in my year would later be associated with the anti-conceptualist Roar Studios.

From the beginning, studying art history at Monash University had a much greater influence on me than the VCA, perhaps because it was more structured and more about ideas. An American Maoist lecturer I had who knew Godard and James McBean (author of Film and Revolution, 1976) – let me astray by telling me to read Foucault.

Paul Taylor was a fellow student. The other American lecturer, Memory Holloway, and Patrick McCaughey, drew you into the world of ideas. It created a lively atmosphere of true believers in contemporary art.

Patrick let me have a wall in the visiting artist’s studio towards the end of 1976. I did large minimalist paintings while sculptor John Davis (who was artist in residence) played with twigs on the floor.

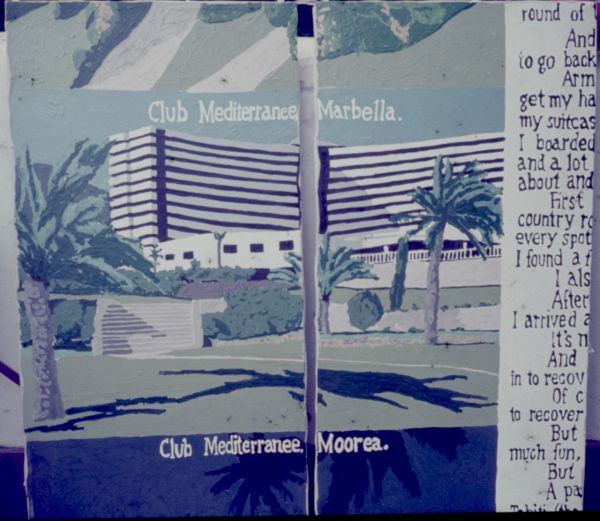

I stopped painting in second year and began making Super 8 film, appropriating imagery about the Vietnam War from leftist magazines. I had become interested in montage. By the end of the year this interest had morphed into paintings of appropriated imagery from popular magazines, such as Women’s Day and New Idea.

I appropriated a photograph of Joh watching television in his lounge while Flo [Florence Bjelke-Petersen, member of the Australian Senate and married to premier Joh] did the ironing beside him. I was as interested in the text as the imagery, and the ironic banality of their juxtaposition. They were painted with as little finesse as possible, which was one of my few strengths then, and perhaps a reaction against how well-crafted the art seemed at the VCA.

A new broom, beginning with painter, printmaker and collage artist Gareth Sansom, went through the VCA in 1977. Maybe I’m exaggerating but, from memory, more than half the students were failed, me included. I had hardly any paintings for assessment, and painting was where it was heading.

The work ethic was back and feminism also finally made it to VCA. When I started, Bea Maddock, in printmaking, was the only woman lecturer. Janine Burke was employed in art history in 1977 and Elizabeth Gower in painting the next year.

I remember Jenny Watson and Lesley Dumbrell also making occasional appearances. Kelly was keen to redress the gender imbalance in what had formerly been a male enclave.

A few years later, after I’d left, he went out of his way to admit painter Trevor Nickolls into the postgraduate program – who must have been the first Indigenous postgrad art student. These new staff made a huge difference. The VCA became a very different and more energetic place.

My impression was that conceptualism didn’t disappear from the VCA but it was on the back-foot, re-emerging elsewhere in the 80s as postmodernism. But then the VCA got a new Head of School, John Walker, who made it a powerhouse of New Expressionism.

Jon Cattapan: We spoke recently of a stint, during your time at the VCA, by the social realist artist Noel Counihan, who taught Drawing. He seems an odd choice given the prevailing attitudes of that era. Can you tell me a little bit about how he came to be there and how you interacted with him?

Ian McLean: Noel probably thought he was an odd choice, too. He was another gentle patient man, and another old communist from the 1930s, 40s and 50s. I was drawn to those historical connections. Like Kelly, Noel was a leftist humanitarian, though he showed his true colours by driving a Citroen – a rarity in those days of high tariffs on European cars.

When Kelly became Head in 1975, drawing was not being taught – another victim of the conceptualism virus. He began teaching drawing that year and, in 1976 I think, brought in Noel to take over from him because the other lecturers didn’t see the point of drawing.

Noel didn’t have a set program. We worked directly from the model but he encouraged us to go our own way. I think Gareth took over drawing some time later. I had lost interest in drawing from the model by then but I heard he had a very different and much more theatrical approach.

Jon Cattapan: Who else was important for you there?

Ian McLean: Coming from Queensland, what was most important to me was the larger Melbourne art scene. People I knew in Melbourne were artists or art students – I had no family or relatives to distract me, it was all art. I even lived with art students. After Brisbane, Melbourne seemed to have endless art galleries, and I discovered New Wave cinema.

The lecturers I first encountered, Paul, Allan and Bea Maddock had a quiet, gentle, thoughtful presence that intrigued me and I came to respect. Kelly I got closest too – we didn’t think the same but we were of similar minds. Gareth, Lesley, Jenny and Janine livened the place up in my last two years but, by then, the VCA had become a small part of my life. Melbourne taught me that art is a big, broad, bickering church, whereas in Brisbane in the early 70s it seemed such a small fragile thing – an endangered species.

Jon Cattapan: After the VCA, you moved into Art History and are now regarded as one of Australia's eminent art historians, and one of the few concentrating on Australian Art. And you have always had a close relationship with contemporary artists. Does having had a sense of practice as an artist play into your reflections?

Ian McLean: I think it counted against me at first. I failed two early essays at Monash, probably because I thought too much like an artist with a disregard for the conventions of art historiography (and writing). Memory always gave me good marks, but I remember John Gregory, a specialist in Baroque art, handing me back my poorly-written essay (no spellcheck, then) and saying. ‘But you’re an art student, you don’t really want to be an art historian’, as if there was no hope for me. That was a real incentive to be an art historian.

I learnt a lot from John about how to write like a proper art historian even though I already a long interest in art history. When I enrolled in the VCA, I also enrolled in an art history unit at Monash University because the VCA did not have a rigorous art history program. This double enrolment was against the rules at the time, but Kelly and Patrick bent them. What’s the point of being the Head if you can’t bend the rules?

So when I finished at the VCA I completed my studies at Monash. It also helped that my girlfriend, Helen Ennis, was a very good art history and English lit major at Monash. Before we did our Honours year we took the Grand Tour. I spent most of the time sketching artworks. It’s a great way to get to know an artwork.

Helen and Ian are now the two named chairs in Australian Art History.

Image courtesy of Ian McLean.

In Queensland’s high school exams we had to draw the artworks we were writing about, from memory. Of course, having been an art student and working in art schools for most of my life impacts on how I look at and think about art. But there’s more to art than art, and this ‘something more’ has always played strongly in my reflections.

Jon Cattapan: You were recently appointed as the Hugh Ramsay Chair of Australian Art at the University of Melbourne. Can you tell us a little about your forthcoming research and what you hope for in your new position?

Ian McLean: As it happened, when I applied for the job I had just signed a contract to write a book on Australian art. Noel Counihan’s close friend from way back, Bernard Smith – who was another important mentor for me – wrote the first national history of Australian art.

I want to write a postnational history of Australian art. I am not yet sure what that means other than it has to be a much bigger story than Bernard’s, which is mainly about paintings by Anglo men. Contemporary art is telling a very different story, and I want to track down its lineage.

It pleases me that in Australia we have the Hugh Ramsay and the William Dobell Chairs of Australian Art History, rather than the Tom Roberts, Sid Nolan or Fred Williams Chair, as Ramsay and Dobell are names that don’t immediately spring to mind as iconic Australian artists.

So, despite the fancy title, it also goes a little against the grain, which is where I feel most at home.