Art and amnesia: the Gallery School and the fate of women artists

By Dr Janine Burke Honorary (Senior Fellow) at the Victorian College of the Arts

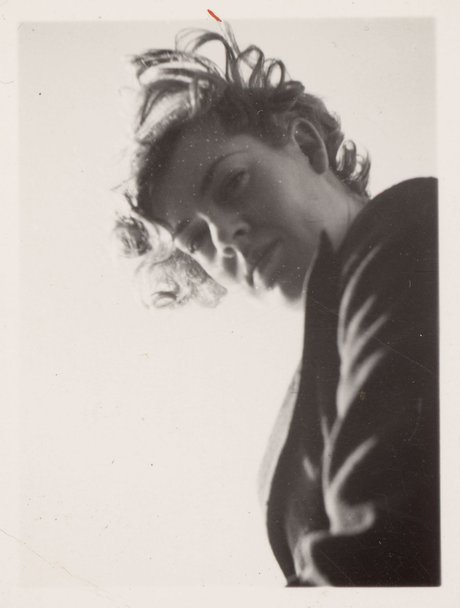

Albert Tucker, ‘Two studies of Joy Hester’ c1940-60. Image courtesy of State Library of Victoria.

As the Victorian College of the Arts celebrates 150 years of art in Melbourne, has anything changed for female artists?

At a recent opening, I was talking with an artist and former Victorian College of the Arts student. I consider her successful – both in terms of the quality of her oeuvre and the money she makes from it. But she was railing against the sexism prevalent in the art world, about her sense of exclusion, her inability to accrue the rewards that male artists did. She was cynical and furious.

Was it just a whinge? Don’t male artists feel neglected, ignored and excluded by the powerful hierarchies that operate in the art world? On Facebook recently, a Canberra-based artist posted a query: “What do curators actually do?” It earned him 30 likes, mainly from other male artists.

My friend’s ire reminded me that perhaps little has changed.

I have found, particularly through my writings on the Australian artist Joy Hester (1920–1960), that it’s not enough to write one book, curate one exhibition about a woman artist and let it rest there. The price of re-discovery, or so it seems, is eternal vigilance; if the flame is not attended it will go out and the reputation of that artist will again sink into obscurity.

I would estimate it is twice as difficult to maintain the reputation of a woman artist as that of a man. I wish I didn't have to say that but experience has taught me otherwise.

In 1975, I curated Australian Women Artists: 1840-1940, which toured during International Women's Year. It turned into a book of the same name, published five years later. The exhibition was first shown at the University of Melbourne’s George Paton Gallery and was commissioned by director Kiffy Rubbo, who was daring, energetic, generous and beautiful.

Looking back, I don't know where Kiffy and I got the nerve to do it. Perhaps we were simply naive. I was 23 and had just graduated in art history from the University of Melbourne. Kiffy was 31. The gallery had never organised a major historical exhibition and was best known for its program of contemporary, accessible and experimental art.

My selection process was to seek artworks of the highest calibre. I wasn't interested in special pleading for women artists and I never have been. I was looking for excellent work – not excellent women's work, but damned good art. I found it, and not always in the most salubrious of places.

Jane Sutherland's misty, elegant, evocative landscape The mushroom gatherers (c.1895) [embed video?] was in the stacks of the National Gallery of Victoria. The painting was in a miserable state. It had become unmoored from its frame and hung askew, the fragile surface rubbing against the harsh dry wood of the mount.

There I was, armed with my notebook and my Polaroid camera, accompanied by a silent, grumpy curator. When I suggested the painting needed immediate conservation, he looked both amazed and irritated. He seemed to feel restoration of such a long-forgotten and unimportant work was unnecessary.

When pressed, he said if it underwent conservation, it would take far too long for it to be included in the show. It was Catch 22. If I wanted it conserved, I could not include it. If I wanted to include it, I could not do so given the appalling condition it was in.

The mushroom gatherers is now one of the NGV's treasures and usually hangs in pride of place together with other members of the Heidelberg School.

There was something else my excursions into the bowels of museums taught me. Women artists may have been forgotten but they were bought, in Melbourne especially, due to a valuable relationship between the Gallery School and the National Gallery of Victoria.

After a student won the prestigious NGV Travelling Scholarship (now the Keith and Elisabeth Murdoch Travelling Scholarship) he or she sent back a painting from their overseas travels, and it became part of the collection. As women won the scholarship every consecutive year from 1908 to 1935, it meant that there was an excellent cache of women artists in the NGV collection.

I found, too, that in times of plenty, when liberal attitudes towards women were stronger, their art flourished. One such time was the turn of the 20th century, the period around Federation.

Women gained the vote in Australia long before the English suffragettes and without their bitterly protracted battle. They were enfranchised in Australia between 1894 and 1908, making it one of the most liberal-minded countries in the Western world. Before World War I, Australia led the world in many area of social reform: it was the first to extend property rights to women, to limit working hours, to grant maternity allowances and support for widows and deserted wives.

A group of women, and former Gallery School students, that included Jane Sutherland and Clara Southern, were active in the Melbourne art world. In 1900, Sutherland was the first woman to be elected to the Victorian Artists Society Council. Clara Southern followed her there two years later.

In 1898, at the Annual VAS exhibition, 27 out of the 52 participants were women. In 1905, the year that Clara Southern, together with Jo Sweatman, May Vale and Josephine Muntz-Adams (all ex-Gallery School students) were council members, half of the artists at the VAS winter exhibition were women. The Gallery School itself welcomed women and the number of women students was often on a par with men.

As far as the exhibition Australian Women Artists went, such figures meant nothing. The real test came when the artworks went up on the walls. The artists looked abundant in their creative energy and ambition. They had produced art that had stood the test of time – art that was complex, deliberate and skillful.

The exhibition challenged Australian art history because it was so good. It didn't ask why have there been no great women artists? It said, here they are. Perhaps the most heartening response came from young women artists who told me, “Now I have a history”.

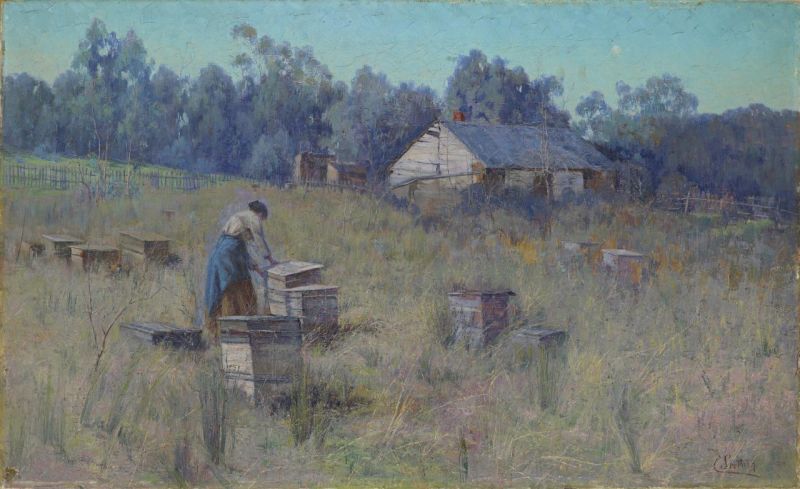

May Vale, The orchard, 1904. NGV Collection.

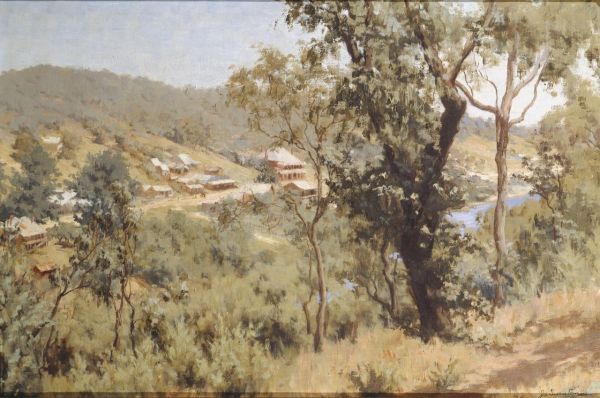

Josephine Muntz Adams, Italian girl's head, 1913. NGV Collection.

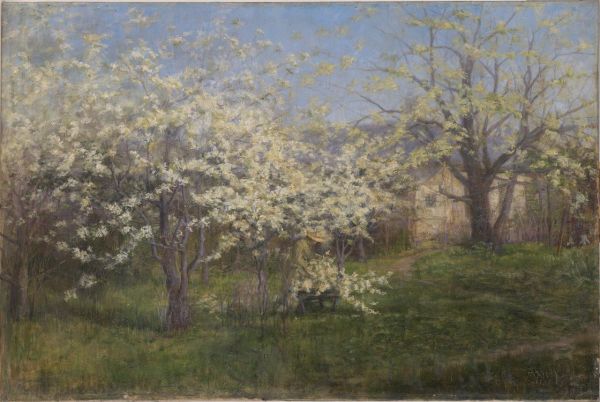

Jo Sweatman, The village, 1931. NGV Collection

Joy Hester

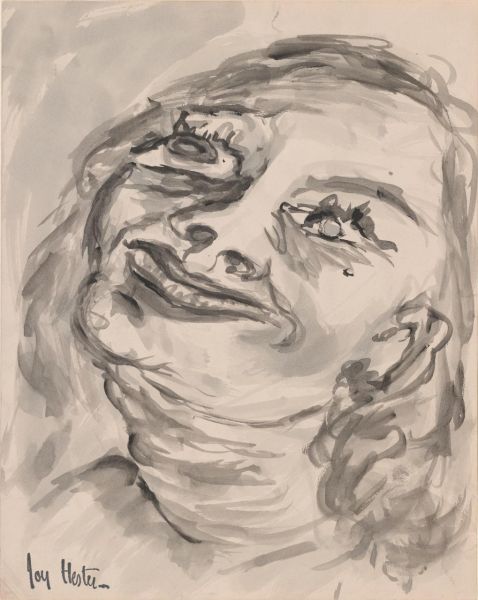

Joy Hester, Untitled –The face of a woman. NGV Collection.

Joy Hester, Untitled –The face of a woman. NGV Collection.

Joy Hester at Watson’s Bay, Sydney, c1939 45, by Albert Tucker.

Joy Hester at Watson’s Bay, Sydney, c1939 45, by Albert Tucker.

Image courtesy of State Library of Victoria.

Joy Hester had the worst-case scenario of a woman artist's life: an unhappy home, a difficult mother, continual grinding poverty, the struggle to produce art and to be recognised, a broken marriage, a life-threatening illness and the battle to do the right thing by her three children.

Hester and Yvonne Lennie were friends and Gallery School students. In 1943, Hester wrote to Lennie with clear and stern advice. “What you want is guts and determination”.

She also told her to study and think about what she had inside her. Not to look at “all knowledge” but to look ”‘only for herself”, warning that, if she didn't do that, “you will lose that thing you feel you have in you and it will bugger you up for years’”.

Lennie ceased making art after her marriage to Arthur Boyd in 1944. Mary Boyd, Arthur’s younger sister, also came in for Hester’s perceptive critique. Mary was wasting her talent and her lack of initiative, of “driving force”, would probably stifle her. Mary also ceased making art after her marriage to John Perceval.

From left: Matcham Skipper, Myra Skipper, Joy Hester, Yvonne Lennie, Arthur Boyd, David Boyd.

1945. Photo by Albert Tucker.

Hester saw her women artist friends disappearing. She could also see their strengths and weaknesses, and knew what it took to go on: guts, determination, driving force. Hester was taken seriously as an artist only by members of her inner circle: primarily Sunday and John Reed, but also Sidney Nolan.

To others, she was defined through the prism of her marriage to fellow artist Albert Tucker. When I began writing Hester's biography, I interviewed several of her male colleagues. “Bert's girlfriend?” they asked. “You're writing a book about Bert's girlfriend?”.

I used to think – hope and pray actually – that one day it would be unnecessary to have exhibitions designated as “women's”. But it seems we need to be reminded, occasionally at least, of the absences and silences in our cultural history, in order to appreciate the confidence and the profusion of women artists today.

This is not a story with a happy ending. It is a story without an ending. There are many creation myths. One is of the snake that swallows its own tail, the ouroborous, a symbol of cyclical change and regeneration. Art is like that. So is the history of women artists. Don’t forget.