Lenton Parr and the birth of the Victorian College of the Arts

By Professor Emeritus Andrea Hull AO

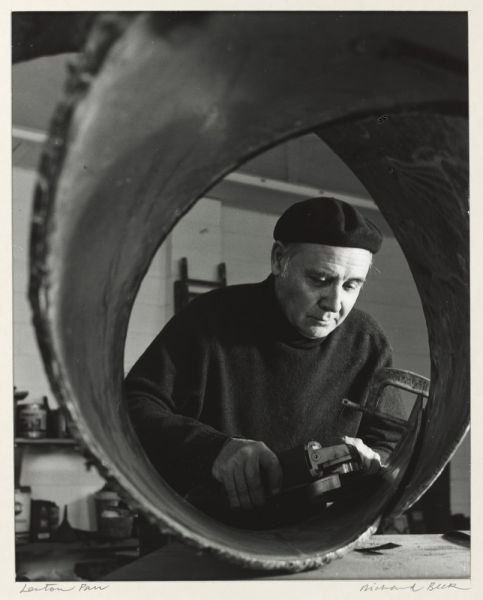

Lenton Parr in 1960s. Image by Mark Strizic. NGV Collection.

Professor Emeritus Andrea Hull AO, Director of the Victorian College of the Arts 1995-2009

Professor Emeritus Andrea Hull AO, Director of the Victorian College of the Arts 1995-2009

Get to know a towering figure in the Australian art world, whose legacy at the VCA continues.

Lenton Parr (1924–2003) became the Founding Director of the Victorian College of the Arts in 1972. Known as an artist, thinker and educationalist of quiet dignity, he was an outstanding formalist sculptor of a distinctive style of constructed or welded-metal sculpture, and also a champion of the atelier mode of educating artists.

Born in East Coburg in 1924, he was a member of the first Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council, chair of the Tapestry Workshop, a Trustee of the National Gallery of Victoria and of the Australian National Gallery, and on various education boards.

He was already in position as Director of the VCA when I first met him. I always enjoyed our exchanges but became more aware of his thinking and writing on the central pillars of quality artists education and training during the CTEC/Australia Council Review of Arts Education and Training 1984/5.

Creating the VCA

The creation of the VCA in 1972 was both deliberate and opportunistic. As Director of the NGV Art School in the late 1960s, Parr saw the tide turning on the funding and structures of post-secondary education.

Backed by a powerful band of political, cultural and philanthropic leaders and the respected Dr Phillip Law as Chair of the Victorian Institute of Colleges, the VCA was stated and created as an amalgam of the arts viz the NGV Art School, Music Performance, Dance, and Drama.

Parr’s dreams were big and contemporary, and further additions included the VCA Secondary School (VCASS), and the VCA’s Film and Television School.

Up until that time, most artists were educated and trained in the Academy model – separate streams, with an apprenticeship component. But, at the very time Parr and his band of supporters were dreaming large, the Disney Brothers in LA knew that their burgeoning animation empire depended on collaborations between artists across the disciplines.

They led the formation of the California Institute of the Arts (CALARTS), which for decades was the nearest international parallel to the VCA. During my tenure as VCA Director (1995-2009) the most fruitful collegial conversations were always with the CALARTS Director.

Manifesto

During my first three months at the VCA as Director in 1995, I met with Parr several times and he gave me many of his documents, including his 1975 overseas report and the Education Specification, The VCA, or manifesto.

Both documents informed his thinking on how the VCA would operate, aspirationally and organisationally. Importantly, the latter document outlined his approach to the education and training of artists.

Today we might call such a document a vision statement or strategic plan. But it was also an eloquent document of significant pedagogical relevance, and the basis for the unique VCA style of teaching.

The critical aspects were:

- to value artists as teachers

- that the education/training of emerging artists was an artfrom in itself

- that the gifted teacher uses Socratic rather than didactic methods and stands behind the students to help reveal their potential and talent

- that talent-based entry was the most valuable form of assessment but that it needed to be backed by desire and commitment, otherwise that talent may travel nowhere.

Parr ensured that the pedagogical values of the NGV Art School formed the core values of the new VCA, and that intensive, specialist, studio-based training and education be provided for all of its outstanding student artists.

Those values were supported by then-contemporary educational concepts such as mentoring by established artists as guest teachers/directors, learning through discovering, and respect for the concept of multiple intelligences.

Above all, the VCA valued the individual artist’s voice, nurtured it and encouraged it to be heard.

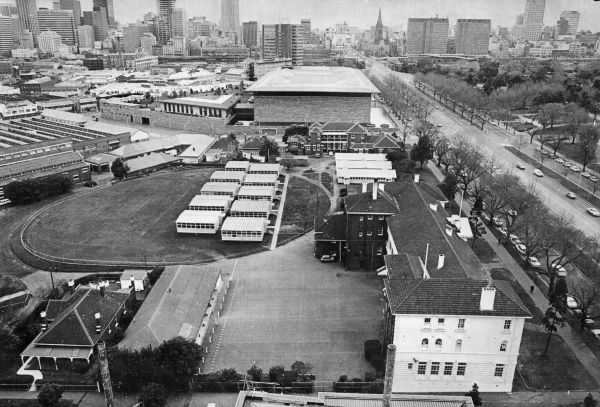

Parr was convinced that the geographic placement of the VCA within Melbourne’s arts precinct – where it continues today – was key to its success, as part of the rich smorgasbord of opportunities for our students and as part of the cycle of renewal of the arts.

He also revealed his hopes for the VCA and its future, many of which were incorporated into my first strategic document as Director. He had envisaged some of the capital works projects we did eventually secure funds for – such as the new Performing Arts building in Southbank, an expanded art gallery, an independent site for the VCASS.

Significantly, he envisaged the securing of the Police Stables on the VCA’s Southbank campus as potentially wonderful artist studios – a project that is currently underway and which is due to be finished by early 2018. That was a case my Council and I pursued for 14 years, and how thrilled Parr would be to see that vision now being realised.

Velvet Glove

Parr was a velvet-glove-and-steel-hand kind of leader. He was quietly-spoken, thoughtful, humble, a man of few words, but always carefully articulated and worth listening to.

His own background was solid in both family and community values, a love of music, the worth of skills, and of training. He drew on his own early trade as a fitter and turner, his wartime experiences.

His early art teaching paralleled with his sculptural practice and, significantly, his apprenticeship to the sculptor Henry Moore and the sense of community he encountered there, to formulate his educational ideals for the VCA.

At the beginning in 1972 he developed the pentagram as the emblem of the VCA. It represented the traditional symbol for the five senses and thus referred, in Lenton’s words, to “the various modes of perception and, by their implication, to their aesthetic functions in the various arts.

“The five principal curves comprising the figure are in reality a single, continuously interweaving band, and this alludes to the unity and interrelation of the several arts the College seeks to promote.”

The logo carried the truth of the place – it was a lived and enacted emblem. For 38 years it was prominent on lapels of staff and supporters, in signage and flags on the campus, on stationery and all publications and graduates’ testaments.

Its tenure ended with the VCA’s amalgamation with the University of Melbourne in 2007, at which point the University’s logo – the “flying angel” – won out.

While the VCA has undergone changes as part of Federal policy and funding, and in now being part of a Faculty within a university where significant research and postgraduate activities abound, the core values of the VCA still reflect the tone of Parr’s visionary 1974 document.

Perhaps this will prove to be his most enduring legacy.