The recent purchase of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, an early printed book with exceptional woodcuts, printed by Aldus Manutius in 1499, was the perfect inspiration for this exhibition based around books from or about Italy. The themes are Politics, Arts, Humanism, Literature, Italians in Australia, Travel and Futurism. Although we try to give an overview of an area, our text focuses on the books in this exhibition. There are obvious omissions, for example works of science, but the focus of this exhibition is the humanities. From a medieval manuscript to a modern day artists book by an Italian Australian, this exhibition shows the range of beautiful and interesting Italian books in the Baillieu Library’s Special Collections. Exhibition curated by Susan Millard, Curator, Rare Books.

Symposium and Opening

Libri exhibition

-

Libri Exhibition

Libri Exhibition -

Libri Exhibition

Libri Exhibition -

Libri Exhibition

Libri Exhibition -

Libri Exhibition

Libri Exhibition -

Libri Exhibition

Libri Exhibition -

Libri Exhibition

Libri Exhibition -

Libri Exhibition

Libri Exhibition -

Libri Exhibition

Libri Exhibition -

Libri Exhibition

Libri Exhibition -

Libri Exhibition

Libri Exhibition -

Libri Exhibition

Libri Exhibition -

Libri Exhibition

Libri Exhibition -

Libri Exhibition

Libri Exhibition -

Libri Exhibition

Libri Exhibition

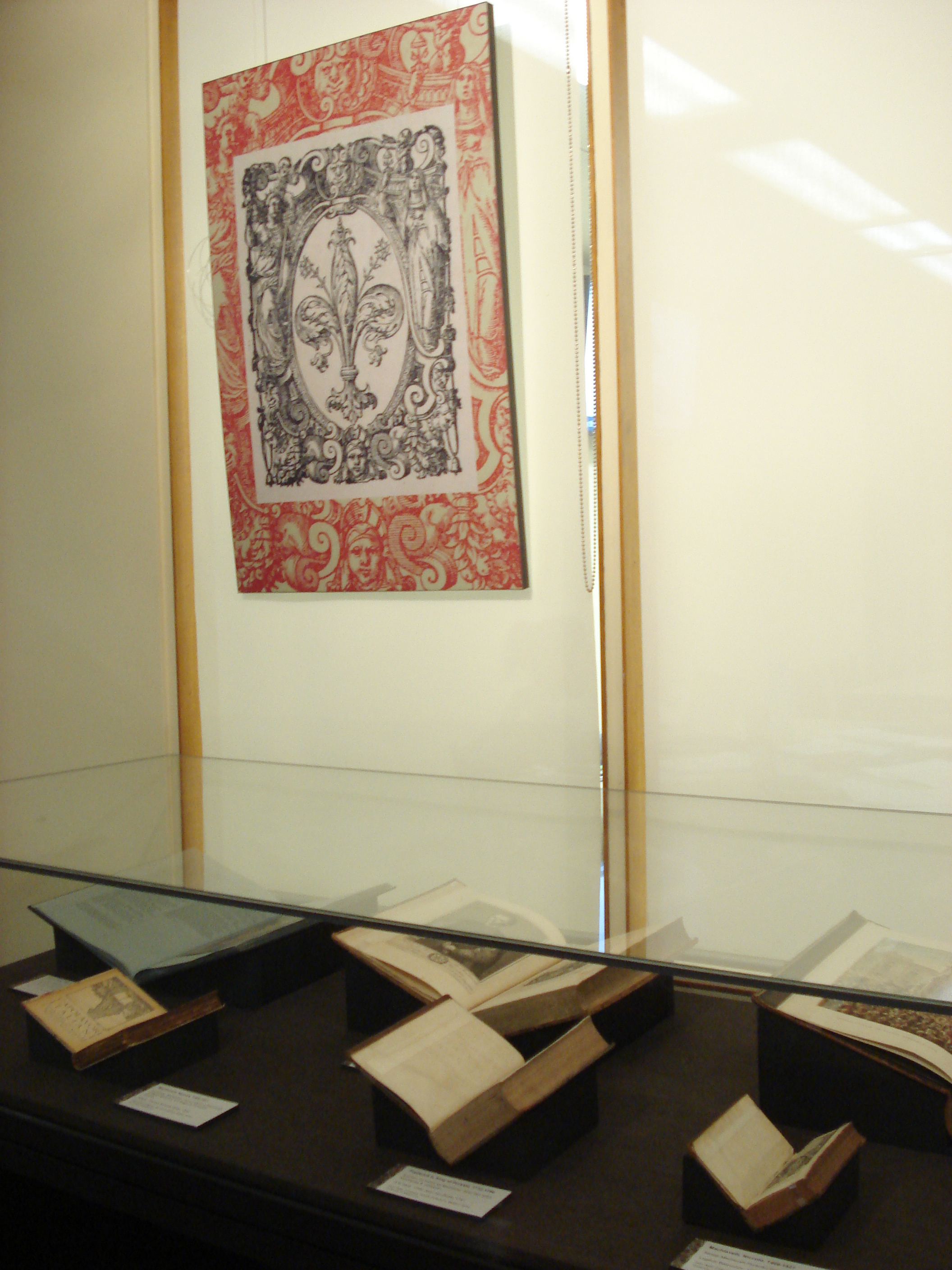

During the late fifteenth to the mid-sixteenth centuries Italy was plunged into the near constant warfare of the Italian Wars, playing host to the political ambitions and squabbles of the great powers of Europe—France, Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Papal States. Rather than the unified nation that we know today, Italy was divided into separate city-states and kingdoms. The fragmentary nature of Italy, its rulers and its armies led to the swift occupation of foreign forces that would rob Italy of its self-determination for the next 300 years. Amidst this turmoil, the people of Italy started to grapple with the ideas of self-determination and the virtues of republicanism. A crisis of identity ensued, with Italians struggling to assert their ‘italianness’. Individuals, powerful families—of the likes of the Medicis, the Sforzas and the Borgias—and even popes, exploited opportunities created by the tumult and sought to legitimise their tenuous hold over their subjects through flamboyant, but ultimately hollow, gestures of power. Inextricably tied to these displays of power, like many aspects of Italian society, was the visual culture of the emerging Italian Cinquecento.

Arguably the most famous personality of Italian political discourse during the Renaissance was Niccolo Machiavelli, a prominent Florentine statesman and political figure who fiercely opposed the ‘barbarous dominion’ of his country. Influenced by classical ideals, he perceived the need for strong and innovative leadership if Italy was ever to assert control of its destiny. He was a prolific author and is commonly heralded as the founder of modern western political thought. His ideas were controversial amongst his contemporaries and were the subject of both praise and criticism. Scholars have argued that his seminal work, The prince, has served as a significant influence on many prominent political thinkers and leaders like Francis Bacon, Descartes and Thomas Hobbes. His theories have also been noted as influencing political thought of the modern era, including the founding of America and Benito Mussolini’s Italian fascism. The University of Melbourne possesses an extensive collection centred on Machiavelli ranging from the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries. These works form the Raab Political Thought Collection, bequeathed by Mr Leo Raab to commemorate his son Felix, a first-class honours graduate in history of the University of Melbourne, who died in 1962 after an accident while walking in the mountains of Calabria.

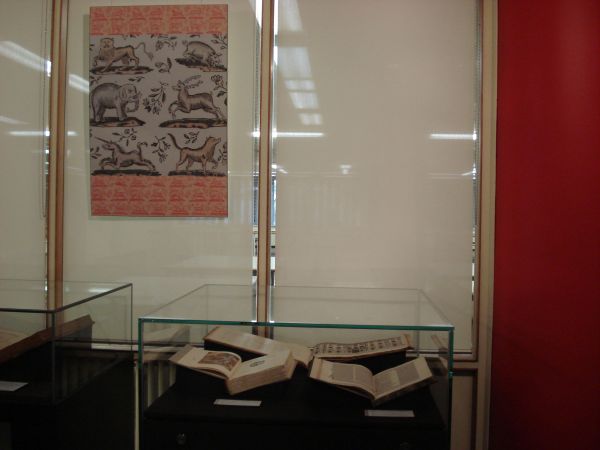

The arts in Italy go back to ancient times and include exquisite medieval manuscripts, but the Renaissance was an obvious high point, with the resurgence of enthusiasm and an outpouring of creativity. The social and political atmosphere is crucial to any art movement and Florence was the perfect setting for a cultural revival, particularly when Lorenzo de' Medici came to power. He commissioned works from Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli and Michelangelo Buonarroti, all great artists of the time. Bartolomeo Scappi, a Renaissance chef who worked in the Vatican, wrote a cookbookin 1570, Opera dell'arte del cucinare, containing around 1000 recipes and notes on cooking, which propelled him to fame. It is thought to contain the first representation of a fork. Many attractive buildings in the old Venetian Republic of the 1500s were designed by architect Andrea Palladio. One of the most important figures in western architecture, he was inspired by Ancient Roman and Greek building design. His text The four books of architecture gained him substantial recognition. Lives of the most excellent painters, sculptors, and architects by Giorgio Vasari is a very early example of an encyclopedia of biographies. Vasari, an artist and architect mixing with Andrea del Sarto, Michelangelo and the Medicis, produced this text, filled with information about artists, some hearsay and gossip. It is believed that he was the first to use the term Renaissance.

This collection represents the literary tradition of the studia humanitatis, or the humanities, in early modern Italian culture. The rebirth of classical ideas, philosophy and art accompanied the humanist tradition that emerged in Europe during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. But it was Italy, with its claim to a rich Roman ancestry, which became the intellectual hub of humanist thought and education among its European neighbours. Studies in Greek and Roman writers saw a revival with the study of such luminaries as Cicero, Sallust and Virgil. Many older, medieval aspects of Italian culture were also embellished with influences harkening back to the Golden Age of the Mediterranean. During this exciting period of intellectualism, subjects that had been held in high esteem in classical times, such as grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry and moral philosophy were popularised and given new importance in Italian culture. Figures such as Leonardo da Vinci, Leon Battista Alberti, Dante Alighieri, Francesco Petrarch, Giovanni Boccaccio and Niccolo Machiavelli are but a few of the many humanists that Italy produced, authors that are still revered to this day. Classical works were translated from Latin and Greek and printed in new, ‘pocket’ editions, often by Aldus Manutius, which could be easily transported and read. This tradition has survived and remained relevant to this day, with classics being translated into a range of different languages and editions. Even e-book versions of these works are available for the casual reader.

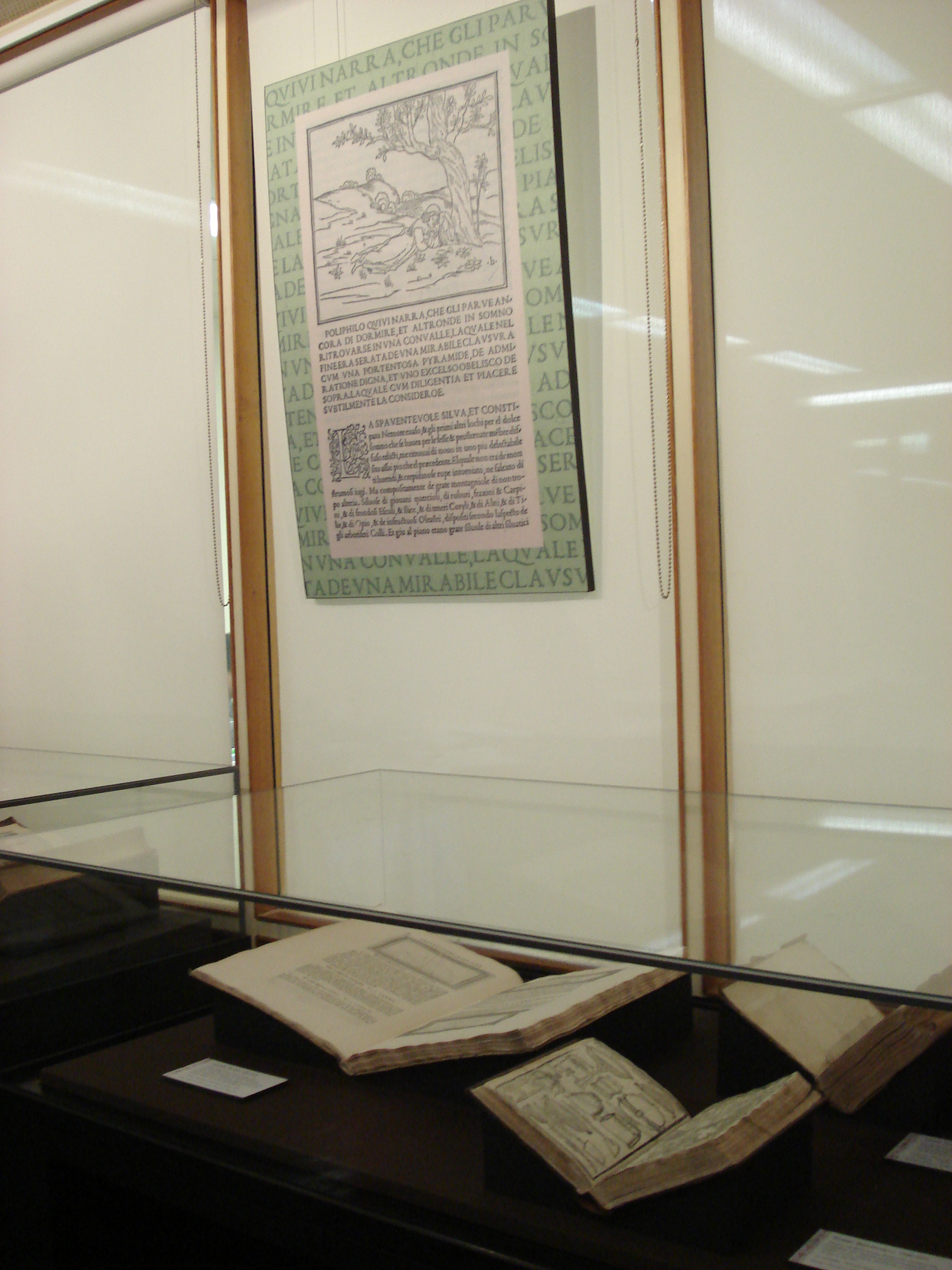

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, an early printed book, was produced in Venice by the venerated printer, Aldus Manutius. It was begun in 1467 and revised until its publication in 1499. The book comes out of the Italian humanist movement of the early Renaissance, probably written by Dominican monk Francesco Colonna. The woodcuts, over 160, are beautiful and, surprisingly, unattributed. The masterful printing and typography also make this work a standout incunable. The influence of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is extraordinary. Although a slow seller originally, it became a benchmark in the areas of architecture and landscape gardening over the following 300 years. There are also passages about mosaics, fabrics, painting, food, music and other subjects. Essentially written in Tuscan dialect, there is also Latin, Greek, Aramaic and his own created language. The story itself, a love story in which Poliphilo is looking for his beloved, is allegorical. Dreams were taken much more seriously at that time and were also used as a vehicle for expounding ideas. Part of the fascination with this book is the mystery surrounding it. There is still a great deal of interest in the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili and much work is being undertaken on the many facets contained within the pages.

The earliest literary tradition in Italy was lyric poetry in Occitan, a language spoken in parts of northwest Italy. The troubadour tradition was strong, with many poets fleeing religious persecution in Languedoc. Eventually a native Italian vernacular emerged. Dante Alighieri produced the Divine comedy in the 1300s, considered one of the greatest works of Italian literature. Its journey into an allegorical paradise, hell and purgatory has fascinated readers through the centuries to the present day. Petrarch, a humanist, delved into the classics of Greece and Rome as his inspiration, but his poetry was a precursor of modern aspirations. Giuseppe Parini, an example of an Enlightenment poet, penned satirical verse, being an influence in the use of blank verse. In the nineteenth century Alessandro Manzoni was an instigator of romantic, but realist literature, writing The betrothed, an immensely popular historical novel set in the time of plague. The early twentieth century saw Svevo Italo, a friend and inspiration to James Joyce, produce Confessions of Zeno, a novel of psychoanalysis that became popular after Joyce promoted it. Eugenio Montale, the Nobel prize-winning poet, and Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, who wrote his one and only novel, The leopard, that was published posthumously, add to the canon of the time. Alberto Moravia was writing at a similar time, however his work was far more hard-hitting and full of existentialist angst, often also anti-fascist. Primo Levi recalls the horror of a Nazi concentration camp in If this is a man, and film director and writer Pier Paolo Pasolini challenges us with gritty realism and his flouting of sexual mores. Unfortunately, after a life of controversy he was murdered by being run over with his own car. More recent authors, Umberto Eco, famed for the medieval thriller The name of the rose, Italo Calvino and Dino Buzzati have produced intellectual but engaging work.

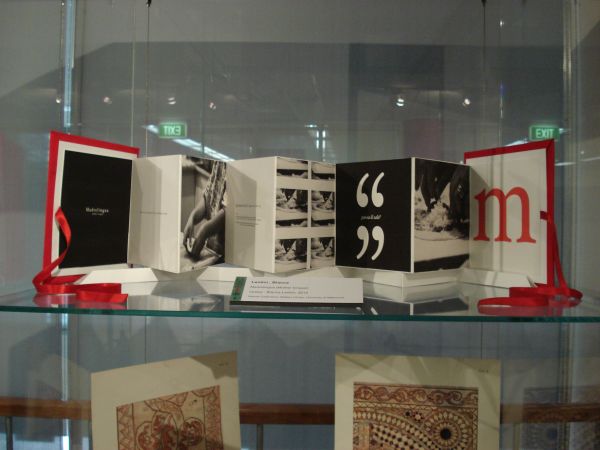

Italian Australians make up around 25% of the population (46% in Victoria) according to the 2006 census. Although Italians have been in Australia since the 1840s and 1850s (particularly during the gold rush), large numbers did not arrive until after World War II. The internment of Italians during the war revealed a hardworking people, as they worked on farms across Australia. Attitudes softened towards Italian immigrants after this and the value of Italians in the economic development of Australia was recognised. Huge numbers came in the1950s and 1960s, often with an eye to a permanent new home, often people sponsored by families already in Australia. Italian culture soon infused Australia with new food and great coffee. Pellegrini’s café in Melbourne reputedly imported the first coffee machine in 1954. Lygon Street in Carlton is lined with Italian restaurants and is a Melbourne institution. Many first and second generation Italians have contributed to Australia in all walks of life. Artists, inspired by their heritage, have produced artists books. Angela Cavalieri uses Italian language and buildings as a basis for her linocuts, Tommaso Durante has used Dante as inspiration for photos of bubbling lava, Bruno Leti has been inspired by the Italian countryside and old buildings, and Bianca Lentini has been moved by her nonna’s cooking. Australia is a much richer place due to the Italian presence and Italian culture is now part of the Australian psyche.

Italy is an amazing country to visit. It is recognised, along with Greece, as the birthplace of western culture, and is filled with art, monuments and a large number of UNESCO World Heritage listed sites. One can experience Etruscan and Ancient Roman civilisation with its incredible ruins and buildings, such as the Pantheon and the extraordinary city of Pompeii, buried under ash in 79AD, through to the beautiful Renaissance cities of Florence and Venice. The idyllic countryside of Tuscany, the stunning coastal towns on the Italian Riviera and the excitement of the large city of Rome are all memorable destinations. Travel to Italy has been an important part of the ‘grand tour’, particularly for the English in the nineteenth century, and is still a must see destination for Australians heading off for their big overseas trip.

Emerging in the early twentieth century, Italian futurism was an artistic and social movement aiming to break with the past. Taking its cue from the modern machine age, where speed, energy, technology and industry created excitement and a feeling of power, artists across the spectrum began creating work that reflected these changes in society. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti is considered the founder of Italian futurism, publishing his Futurist manifesto in 1909. Another aspect of this movement was fervent nationalism and militarism. The striking feature of much of this work is the bold typographical style, influencing many subsequent art movements. Bruno Munari was part of the second futurist movement in the 1920s, but distanced himself as it took on fascist sympathies, as did many other artists.