Gothic Realities: Tabloid Coverage of the Macabre in the Nineteenth Century

Dr Una McIlvenna, Faculty of Arts, University of Melbourne.

There is a common misconception that the nineteenth century ushered in a time of restraint and manners, when polite society shuddered at the thought of unbridled passions and moral decline. But the reality was that popular interest in sensationalist stories of violent crimes, dramatic natural disasters, and bloody accidents reached an all-time high in the Victorian era.

Those features so common from gothic literature—untamed emotions, the wild natural world, the vulnerable in danger from arch-criminal monsters—can all be found in the cheap press of the nineteenth century. In both Britain and France, graphically illustrated periodicals such as the Illustrated Police News or L’Oeil de la Police featured stories of murders and assaults at home and abroad, or macabre events like maulings by wild animals escaped from the zoo or runaway trains crashing off bridges. There was also a fierce trade in cheaply printed broadsides featuring ballads about criminals being executed or terrible industrial accidents, set to tunes that deliberately tugged at the heartstrings. Everywhere the appetite for melodramatic, highly emotive news about horrible events was whetted by a constantly growing production of cheap print that painted a picture of a gothic nightmare, where the savage world was always present and ever-threatening.

Tabloid journalism

First published in 1864, the Illustrated Police News was a weekly illustrated British newspaper. An early version of a tabloid, it featured dramatic stories of murders, outrages, executions, accidents, and macabre events, all graphically illustrated in detail.

In one front page alone, on Saturday 20 July 1867, we can find detailed pictures with the accompanying headlines:

‘Accident to Wombwell's Menagerie - Horses Attacked by Wolves’

‘Desperate Encounter with a Jackal - A Man Seriously Wounded’

‘Attempted Murder of a Policeman at Ashton-under-Lyne’

There are also stories on the front page of a horse and rider falling off a bridge into the river below and a man being shot in the street. A single glimpse at this typical page reveals a world of extraordinary and unpredictable violence: whether it was the savagery of wild animals like wolves and jackals attacking humans or domesticated animals, or the fiery and fatal passions of wronged lovers or hardened criminals, the message from these stories was that one could not predict where the next horror would come from. Even innocent people were constantly menaced by the fierce and wild nature lurking underneath a calm exterior. The French even had (and still have) a name for this kind of story: faits divers. The same kind of reports of dramatic events, also with detailed illustrations, featured there in periodicals like Le Petit Journal and L’Oeil de la Police.

Criminal anthropology

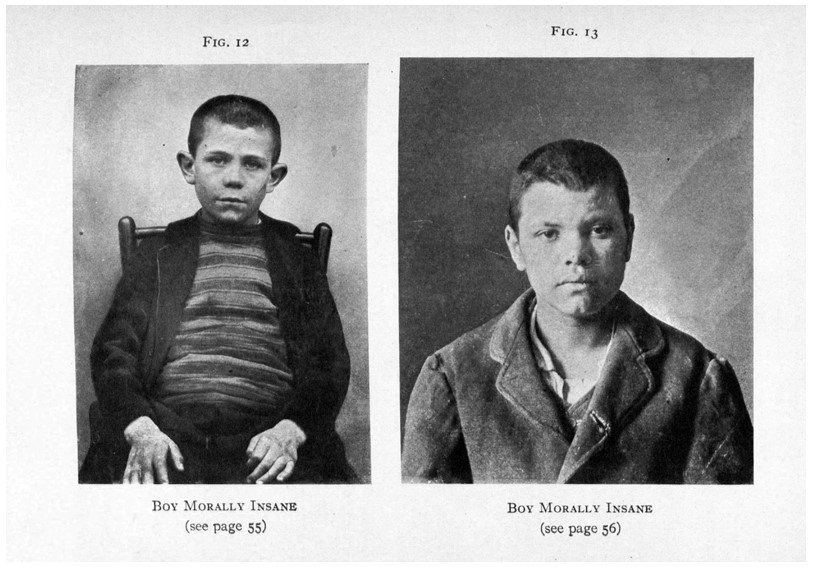

As the urban populations of Britain and France increased in the nineteenth century, so too did anxieties around poverty, criminality, and promiscuity. The idea of the ‘criminal underclass’ became prominent, aided by the new discipline of criminal anthropology, espoused by the influential Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909). Lombroso measured and analysed the bodies of hundreds of living and executed criminals to draw up a scientific typology of characteristics. The idea was that criminality was inherited, and that those who were ‘born criminal’ could be identified by physical defects, which confirmed a criminal as savage. For example, based on a theory that criminals were unable to blush (blushing being a sign of conscience and remorse), Lombroso’s studies claimed that of a sample of 122 female criminals, 79% of murderers, 82% of infanticides and 90% of thieves could not blush. This concept of the ‘born criminal’ fascinated the public and informed both the news reporting of crime as well as the depiction of arch-criminals in Gothic literature.

Execution ballads

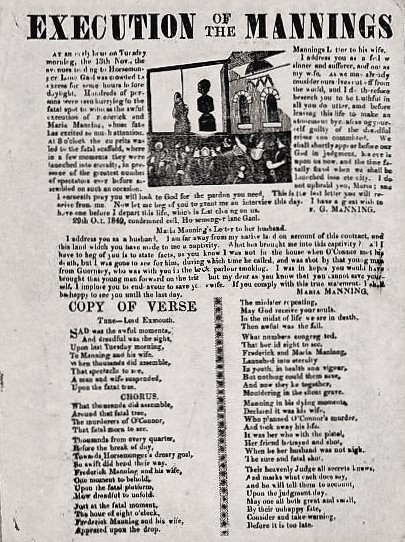

One perspective on this depiction of criminals can be gleaned from the ever-popular genre of execution ballads, songs that detailed the crimes and punishments (in Britain, usually hangings; in France, hanging or by guillotine) of exactly the kinds of ‘born criminals’ Lombroso claimed could be identified by visual characteristics. While execution ballads had been one of the most popular sub-genre of ballads since the sixteenth century, their production soared in the nineteenth century due to improved printing technology, and a single songsheet could be sold in the millions. One example of the popularity of these dramatic or gruesome songs about criminals is the case of Maria and Frederick Manning, a couple hanged outside Horsemonger Lane Gaol, London, on 13 November 1849, for murdering her lover, Patrick O'Connor, so that they could rob him. The case became a cause célèbre largely because it was the first time a married couple had been executed together since 1700, and there was particular fascination around the figure of the Swiss-born Maria Manning: portrayed in the press as an adulteress, a thief, and a murderer, she embodied many of the fears that haunted Victorian society: fears of immigration, sexual promiscuity, and moral degeneration.

Their execution attracted thousands, and the novelist Charles Dickens wrote an extraordinary letter to the Times about his experience there. Henry Mayhew, the chronicler of nineteenth-century London street life, claimed that 2.5 million copies of broadsheets about the Manning executions were sold.

One of those was this song ‘Execution of the Mannings’ which you can listen to here:

Its opening verse is a good example of the emotive language used to describe the scene:

Sad was the awful moments,

And dreadful was the sight,

Upon last Tuesday morning,

To Manning and his wife.

When thousands did assemble,

That spectacle to see,

A man and wife suspended,

Upon the fatal tree.

The Manning case demonstrates what an appetite there was for the macabre in nineteenth-century popular culture. Attending executions in their thousands, reading stories and singing songs about horrific crimes and accidents, Victorians looked for drama, fear, and suffering in their daily lives. The tabloid journalism that marketed to them provided a daily feast of gothic themes: in their stories we see the savage within the natural world, and the diabolical within the human.