Mezzotint might just be the perfect medium for gothic imagery as the artist begins with a completely dark, almost terrifying, surface and gives their image life by drawing with light. Renowned English examples of this luminous art form hang in the exhibition Dark imaginings.

The technique of mezzotint first emerged in the 17th century in the Netherlands and was embraced by English printmakers where it rose to great prominence in the 18th century.[1] It was the evolution of experimentation with marks on a plate, and it broke with traditional printed image making as it is not based in line work, but rather tones. A mezzotint is created by abrading a metal plate, usually with a special tool called a rocker. When the plate is inked, this burred surface provides the rich velvet black so characteristic of the medium. To draw the image, the artist works with another tool, often a burnisher to smooth out the pitted areas of the plate thereby creating tones which form the image. In the current century, it still used by artists, but more as a technical marvel than as it once was: a leading national mode of expression.

Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797), an artist renowned for candle-lit subjects, selected this pioneering technique to reproduce his atmospheric paintings. Wright was working in the grip of the scientific revolution, yet has chosen to represent a branch of pseudo-science in An Alchymist. These early styled chemists were driven to discover the philosopher’s stone, or in other words, the secret to transforming base metals into gold. On a moonlit night, we find Wright’s archaic alchemist kneeling transfixed before a heating flask of urine at the moment it emits a jet of vapour. This scene has come to be the model for the night in 1669 when Henning Brand, the German alchemist, probed urine for the philosopher’s stone and unexpectedly discovered phosphorus.[2] Rather like a mezzotint, phosphorus trades in light and it emanates a beguiling glow. Phosphorus is an important and dangerous scientific element, playing a role in medicine, match invention and war, but it also a suspect in more mysterious phenomena, including ghosts. This picture eerily projects a moment of the past, and a gothic persona: in his lair on the fringe of mainstream society, working at his foul experiments.

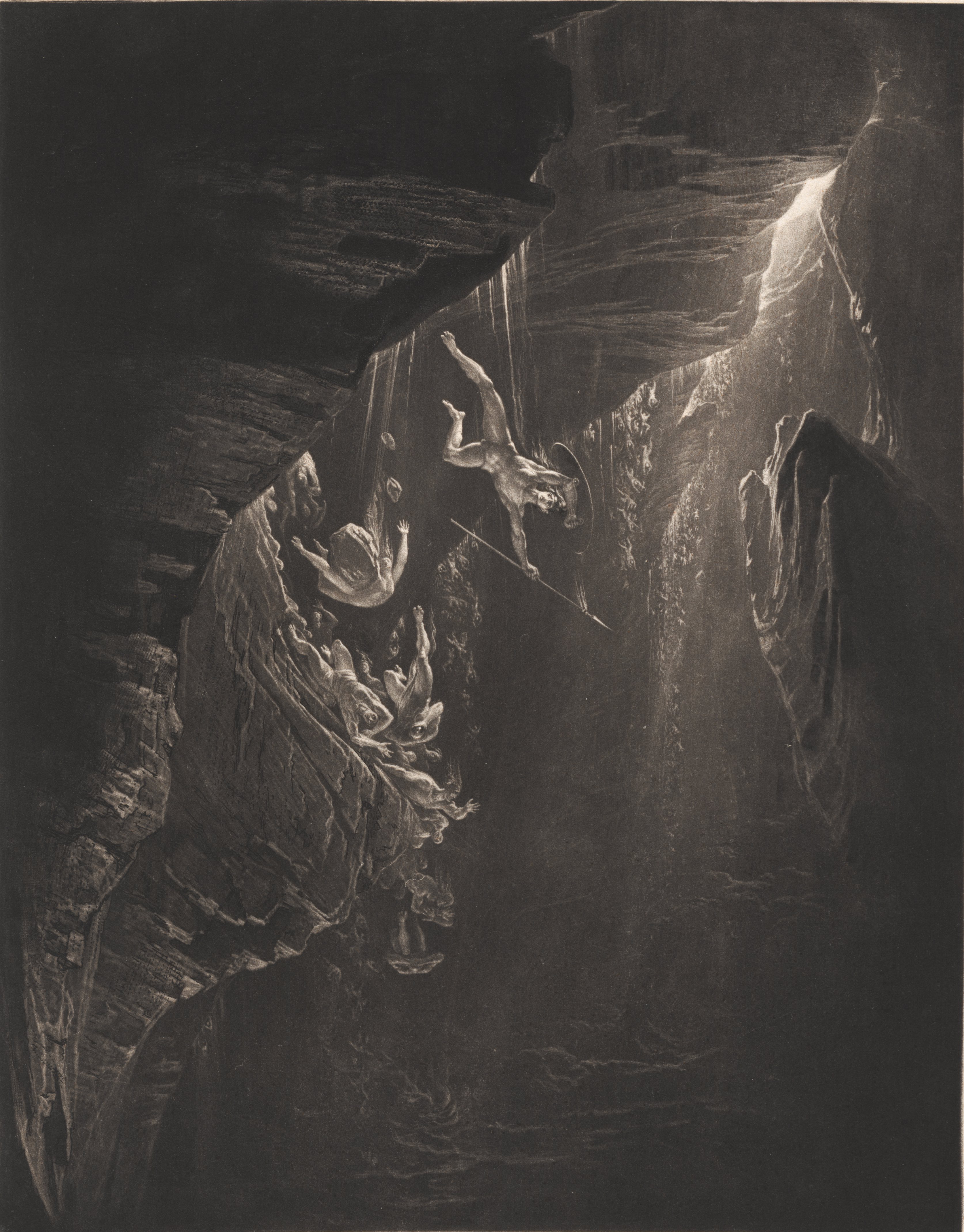

As the century gave way to a more romantic rendering of gothic archetypes, such as Victor Frankenstein in the 19th century, further settings and characters were drawn by literature. In rather arresting terminology, one scholar classified John Martin’s (1789–1854) mezzotint illustrations for the pulsating epic Paradise Lost as ‘apocalyptic romanticism.’[3] The Baillieu Library is very fortunate to hold a complete set of the 24 proof images for this project,[4] made between 1824 and 1825, and six of these mezzotints are on display in the exhibition. While neither the illustrations nor the text sit comfortably in any one genre, Martin’s images are mesmerising exemplars of the art and they sprang directly from his imagination onto the soft steel printing plate.

The Fall of the Rebel Angels is the opening image for the series and the first to exploit the potentials of the medium, which may be seen through Martin’s use of black to convey infinite space. So, that: ‘The viewer is left to his own imagination to create the “bottomless perdition” of the depths of Hell from the blackness into which Satan and his legions fall.’[5]

If Martin could wield blackness so effectually, then it will come as no surprise that he was also a master of the application of light. The fundamental role of the image Creation of Light was to visually capture the moment in the Bible when light is brought forth from darkness. Martin achieved this objective so well that this image is regarded as one of his greatest and best known achievements in printmaking.

If Satan and his accomplices are condemned to the darkness the viewer, by contrast, is like a good angel, seduced toward the light in these prints. As Wright used a candle for a light source, it is almost as if Martin’s apertures of light open from an omnipotent source beyond the sheet. They are executed with a technical valour which draws us into their fathoms.

Romance in visual art and literature was often inhabited by ominous forests, architecture or other dark locations such as graveyards, but romance took on more risqué associations through the development of ‘Romantic Science.’ When the botanist Carl Linnaeus developed a system of taxonomy and began to discuss plants in terms of their sexuality, then nature became animated and the academy became enlightened.[6] These ideas are rapturously embodied through Robert Thornton’s book, Temple of Flora (1799) which lavishly illustrates this new, romantic nature.

The Dragon Arum or Dracunculus vulgaris is a dangerous bloom designed to lure insects into its maw of death. As a mezzotint, it layers the versatility of the medium through the introduction of colour, and by placing the specimen before a heaving backdrop from the natural world.

Portraiture would become the most popular subject for mezzotint—the likeness of Lord Byron in the exhibition is an example. Mezzotint evolved beyond these beginnings as a method to tonally reproduce paintings and John Martin was one of its practitioners who freed its artistic bounds. From dark imaginings, and experimentation, came mezzotint, and paradoxically from mezzotint, came light.

footnotes

- Carol Wax, The mezzotint: history and technique, New York: H.N. Abrams; London: Thames and Hudson, 1990, pp 15–24

- John Emsley, The shocking history of phosphorus: a biography of the devil's element, London: Macmillan, 2000, p 4

- Gordon N. Ray, The illustrator and the book in England from 1790–1914, Dover Publications, New York, 1976, p 44

- The set was issued in four separate editions.

- Michael J. Campbell, John Martin: visionary printmaker, [England]: Campbell Fine Art in association with York City Art Gallery, c1992, p 42

- Martin Kemp, ‘Sex and Science in Robert Thornton’s Temple of Flora,’ 2000, https://publicdomainreview.org/2015/03/11/sex-and-science-in-robert-thorntons-temple-of-flora/ , accessed November 2017